Classical CDs: Violins, timpani thwacks and a symphony of iron and steel | reviews, news & interviews

Classical CDs: Violins, timpani thwacks and a symphony of iron and steel

Classical CDs: Violins, timpani thwacks and a symphony of iron and steel

A birthday tribute for celebrated violinist Gidon Kremer, plus symphonies, operetta and a great 20th century piano concerto

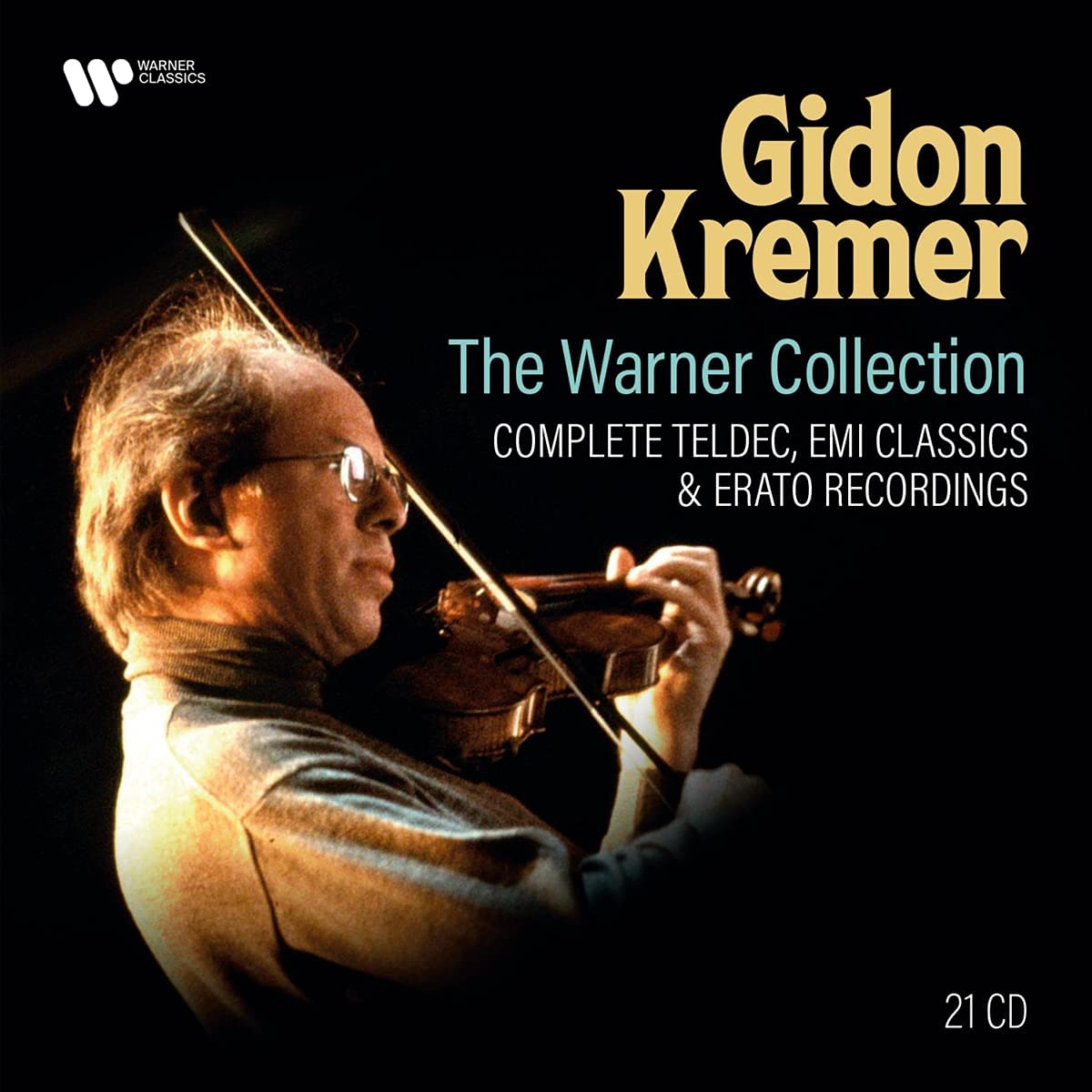

Gidon Kremer: The Warner Collection (Warner Classics)

Gidon Kremer: The Warner Collection (Warner Classics)

The words of dedication in Gidon Kremer’s autobiography, Between Worlds (2003) are chosen with care. The book is, he wrote, for “all those who are seeking their way”. The Latvian-born violinist’s own path through music has been as wide-ranging as it has been radical. With his 75th birthday (27 February) imminent, this new 21-CD box from Warner shows his presence and influence through the scope and the breadth of an extensive anthology of recordings for three labels, EMI, Erato and Teldec.

Kremer has never limited himself to standard repertoire. As he comments in his autobiography, remembering his early experiences of building recital programmes: "It was not the stringing-together of popular works that appealed to me, but the attempt to offer unexpected contrasts." So, on this set we witness his indispensable role as an advocate for contemporary composers such as Schnittke, Vasks, Valentin Silvestrov and Astor Piazolla (his complete tango opera María de Buenos Aires).

Contrast, then, is an ever-present theme in this anthology. Having said that, it should also be noted that this box does not give us the "man in full". That is because, ever since he emerged from the Soviet system and moved to the West, Kremer has deftly and consistently ensured that his recorded oeuvre should continue to appear on various labels. It still does. So what we don’t have here is any of the early output on Melodiya. Nor do we find that cornerstone, his long and productive relationship with Deutsche Grammophon. DG has issued more than 20 concertos, and UNESCO-worthy monuments like the complete Beethoven sonatas with Argerich, plus important albums of Gubaidulina and Weinberg. Meanwhile, a search for Kremer’s most popular track on Spotify takes us to ECM, and Kremer’s recording of Arvo Pärt’s “Fratres” with Keith Jarrett, from the cult 1984 album Tabula Rasa; Manfred Eicher has been loyal, and his label now has a substantial catalogue, mostly of Kremerata Baltica, of more than 20 albums. There have also been ventures with Sony/CBS, up to and including a fascinating 2021 album of works by Miłosz Magin (1929-1999). I must also confess a sweet tooth for one particular offering of Viennese Confiserie-Kunst: the album of Strauss/Lanner polkas and waltzes with Peter Guth from 1982. That one was on Philips.

There is a lot more of Kremer on other labels, then, but his passion and commitment as interpreter to the music he plays are everywhere in this box. There might not be a better example of that than the sheer power of the opening of the premiere recording of the Schnittke “Concerto for Three” with Bashmet and Rostropovich; it just jumps out of the speakers. As our fellow TAD writer Gavin Dixon (whose Schnittke handbook is about to appear) has reminded me, Kremer had an incalculable impact in ensuring that Schnittke’s works were heard in the West: he was already championing the composer in the 1970s. Both this triple concerto and the 4th Violin Concerto, dedicated to Kremer, also here, make use of the violinist’s musical "monogram" G-D-E-E, Schnittke’s expression of deep gratitude to him.

There is a lot more of Kremer on other labels, then, but his passion and commitment as interpreter to the music he plays are everywhere in this box. There might not be a better example of that than the sheer power of the opening of the premiere recording of the Schnittke “Concerto for Three” with Bashmet and Rostropovich; it just jumps out of the speakers. As our fellow TAD writer Gavin Dixon (whose Schnittke handbook is about to appear) has reminded me, Kremer had an incalculable impact in ensuring that Schnittke’s works were heard in the West: he was already championing the composer in the 1970s. Both this triple concerto and the 4th Violin Concerto, dedicated to Kremer, also here, make use of the violinist’s musical "monogram" G-D-E-E, Schnittke’s expression of deep gratitude to him.

The partnership with Harnoncourt on Teldec is important, too. There is a fine recording of the Beethoven Concerto here with the Chamber Orchestra of Europe, and of Brahms (violin and double concertos) and also a lovely recording of the Schumann concerto, paired with Marta Argerich playing the piano concerto. The Brahms and Schumann concertos appear elsewhere in the box too: The "other" Schumann concerto is with Muti. It is distinctly stodgy when compared with Harnoncourt’s lithe energy. The other Brahms concerto is the 1976 one with Karajan and the Berlin Philharmonic: that was the occasion when 19,000 of Kremer’s 20,000 Deutschmark fee was trousered by officials in Moscow. It also gave rise to a famously supportive quote from Karajan (picked up again in the booklet essay) which Kremer, no admirer of star systems, says he has always been uncomfortable with: that Kremer is “the best violinist we have.”

The violinist’s pianist colleagues are a fascinating collection. Above all there is Argerich, with a two-disc Berlin recital from 2006. A joyous moment here is her solo feature, Schumann’s complete Kinderszenen. There is Oleg Maisenberg too: his playing on a CD of Enescu (the Impressions d’Enfance), Schulhoff and Bartók is ferocious, even daemonic. And then there is a 23-year old Andrei Gavrilov from 1979 launching into Weber with the “charming insouciance” to which Kremer says he has always felt happily drawn. We also find Berg with the CBSO and Simon Rattle plus a whole Erato disc of Britten. This box is a gift which keeps on giving and revealing more treasures. Happy 75th, Gidon Kremer.

The violinist’s pianist colleagues are a fascinating collection. Above all there is Argerich, with a two-disc Berlin recital from 2006. A joyous moment here is her solo feature, Schumann’s complete Kinderszenen. There is Oleg Maisenberg too: his playing on a CD of Enescu (the Impressions d’Enfance), Schulhoff and Bartók is ferocious, even daemonic. And then there is a 23-year old Andrei Gavrilov from 1979 launching into Weber with the “charming insouciance” to which Kremer says he has always felt happily drawn. We also find Berg with the CBSO and Simon Rattle plus a whole Erato disc of Britten. This box is a gift which keeps on giving and revealing more treasures. Happy 75th, Gidon Kremer.

Sebastian Scotney

Beethoven Revolution Vol. II, Symphonies 6 to 9 Le Concert des Nations/Jordi Savall (Alia Vox)

Beethoven Revolution Vol. II, Symphonies 6 to 9 Le Concert des Nations/Jordi Savall (Alia Vox)

Coming to a Beethoven symphony cycle midway is like arriving late to a party, and savouring this period instrument set of the last four symphonies has left me desperate to sample the earlier volume. We’re lucky to have this three-disc set at all; conductor Jordi Savall outlines the various pandemic-related complications which almost put paid to the project. Which might explain the buzz and energy which these performances possess. No. 6 can be a bit of a snooze in the wrong hands, but flowing tempi and a pleasingly bright, lively orchestral response make Savall’s reading a delight. Oft-hidden details like the flutes’ bird calls in the exposition ring out, and the development’s minimalist murmurings sound strikingly modern. This “Scene by the brook” is a joy, and the scherzo’s winds and horns are superb. Best of all is the storm sequence, the drama enhanced by seismic timpani thwacks. Symphony No. 7 has an irresistibly feisty kick to it; the occasional rough edges in the playing all to the good. The shift to A minor between the first two movements is really startling here, Savall ramping up the cheekiness of Beethoven’s “Presto” and letting rip with an ebullient finale. It’s really, really good.

Smaller forces allow our ears to unpick Symphony No. 8’s inner workings unusually easily, the outer movements combining punch with balletic grace. No. 9 is stark and powerful, though you sense that Savall’s sympathies really lie with the two fizzier symphonies which precede it. He has an excellent quartet of soloists, with La Capella Nacional de Catalunya offering fulsome choral support. Though it’s the orchestral details which stand out, especially the slow movement’s wind solos and the symphony’s clangourous coda. The hybrid SACD recordings, presumably made live in three different venues, are detailed and transparent. Highly recommended, then. Do watch out for the improbably thick multilingual booklet, which has a tendency to fall out of the digipack just when you think you’ve secured it into position.

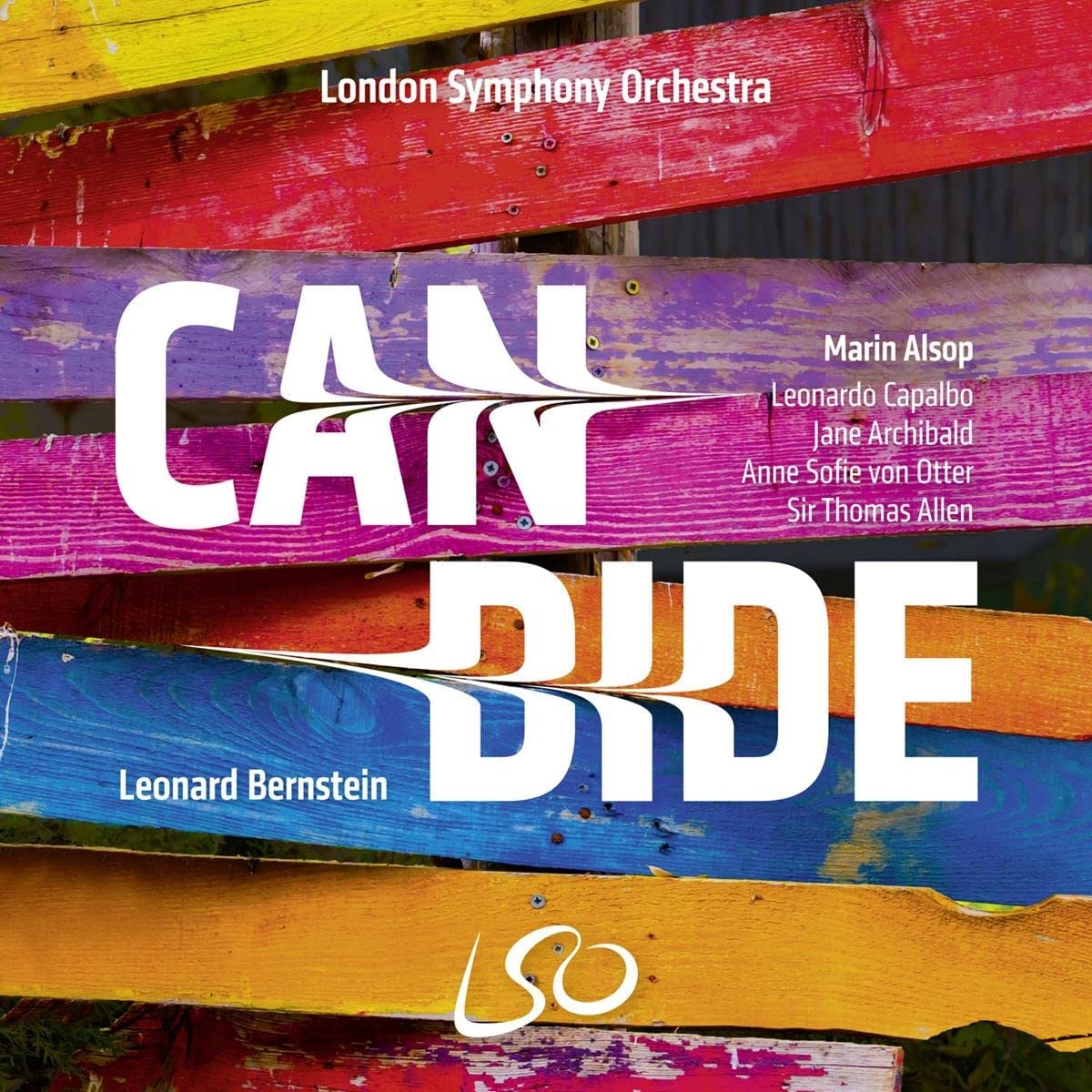

Bernstein: Candide Leonardo Capalbo, Jane Archibald, Anne Sofie von Otter, Sir Thomas Allen, London Symphony Orchestra and Chorus/Marin Alsop (LSO Live)

Bernstein: Candide Leonardo Capalbo, Jane Archibald, Anne Sofie von Otter, Sir Thomas Allen, London Symphony Orchestra and Chorus/Marin Alsop (LSO Live)

Keeping up with the various incarnations of Bernstein’s operetta Candide is an exhausting business, as you’d expect from a work with a list of collaborators as long as your arm. Marin Alsop’s new version, taped live at the Barbican in December 2018, is described as “based on the 2004 Lonny Price production for the New York Philharmonic and Marin Alsop”. Broadly similar in structure to the score which Bernstein conducted in London in 1989, Alsop is zippier and less indulgent than her mentor. Bernstein’s late recording now feels too slow and indulgent, though the spiritual oomph he brings to the closing chorale still hits the spot for me. Alsop’s tempi aren’t that much faster than Bernstein’s, though, as Jessica Duchen points out in her review of the live performance, they do allow us to hear every word.

Leonardo Capalbo and Jane Archibald are convincing as Candide and Cunegonde; the former’s “It Must Be So” is touching, and Archibald has fun with “Glitter and Be Gay”. Anne Sofie von Otter’s Old Lady switches accents with impressive ease, and Sir Thomas Allen gives us a warmly sympathetic Pangloss. Smaller roles are well cast. An improbably large London Symphony Orchestra never sounds heavy-footed, and the LSO Chorus are superb. But, compared to On the Town and West Side Story, this Candide sounds baggier and less coherent with repeated listenings, a sequence of brilliant numbers linked by Allen’s irksome narration. Still, “Bon Voyage” and “What’s the Use?” are great fun here, and Alsop’s finale is resplendent. Production values are impressive, and a decent notes plus a full libretto are included. If in search of a "complete" recording, start here. Next, seek out the original Broadway cast album and the 1990 National Theatre disc – both incomplete but more musically satisfying overall.

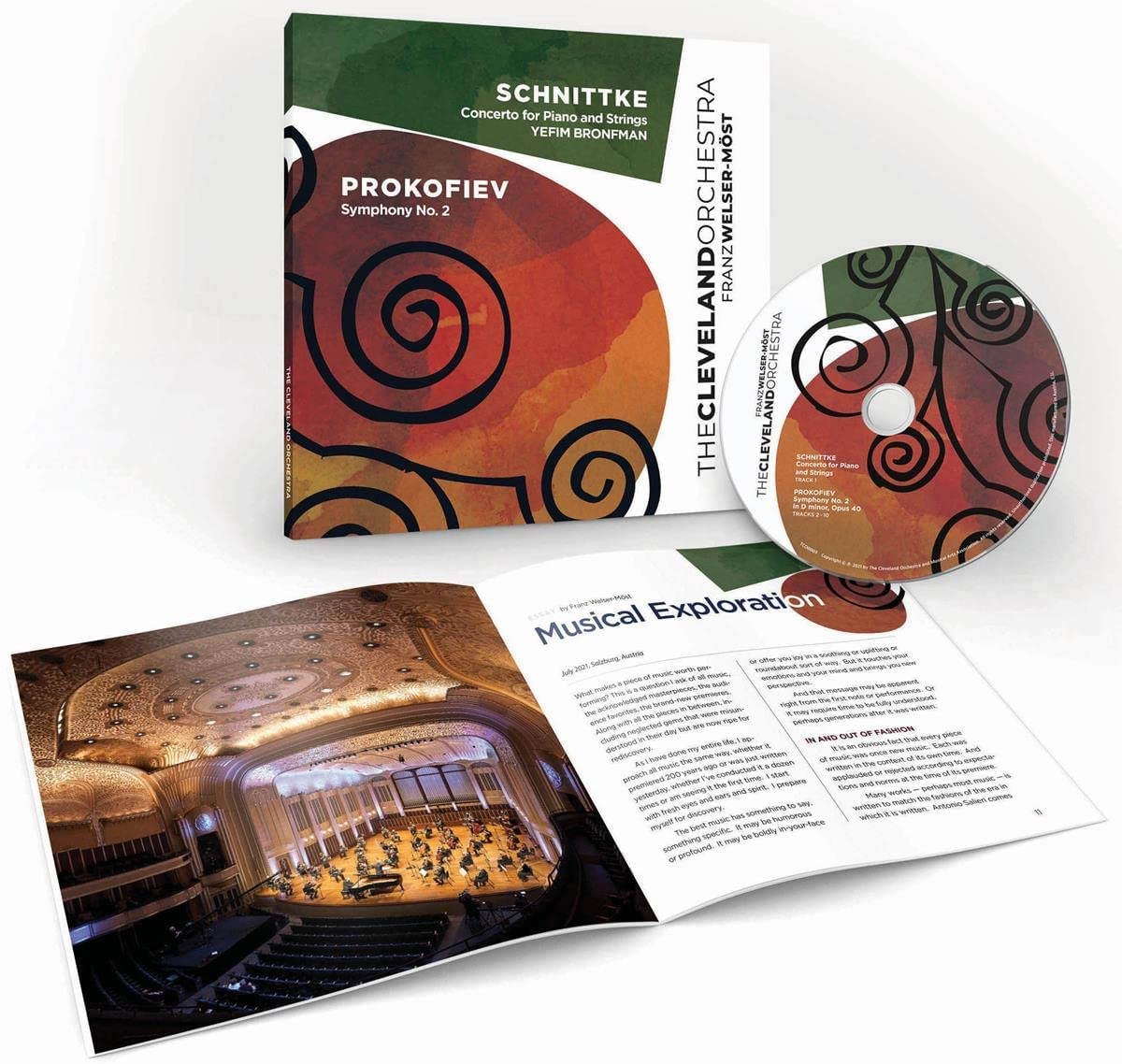

Schnittke: Concerto for Piano and Strings, Prokofiev: Symphony No. 2 Yefim Bronfman (piano), The Cleveland Orchestra/Franz Welser-Möst (Cleveland Orchestra)

Schnittke: Concerto for Piano and Strings, Prokofiev: Symphony No. 2 Yefim Bronfman (piano), The Cleveland Orchestra/Franz Welser-Möst (Cleveland Orchestra)

Listen to Prokofiev’s first two symphonies side by side and you might wonder if they’re from the same pen, so different do they seem in mood and sound. Hugh MacDonald’s booklet essay accompanying this Cleveland Orchestra own-label release makes the point that, with Symphony No. 2, “the better an orchestra manages to play its challenges, the clearer the line is drawn between music and noise.” As with Andrew Litton’s recently reissued Bergen performance, Franz Welser-Möst makes Prokofiev’s exhilaratingly brash first movement sing. The trumpet blasts in the opening bars are piercing but sonorous, and it’s refreshing to hear the orchestral piano writing so clearly. The wind writing looks forward to that in Stravinsky’s Symphony in Three Movements, and there’s some sonorous, incisive playing from cellos and basses. Welser-Möst shapes the second movement’s lyrical theme with tenderness and affection, injecting plenty of character into the variations which follow. It’s a fabulous symphony, Prokofiev capping the theme’s return with an incredibly disconcerting quiet chord. If you don’t know the work, start here; I like the brash, chaotic power which Neeme Jarvi on Chandos brings to the music but Welser-Möst is easier on the ears.

The coupling is Schnittke's remarkable single movement Concerto for Piano and Strings, with Yefin Bronfman as soloist. He's a compelling guide to one of the 20th century's great concertante works. Schnittke's piano writing mostly eschews virtuosity and much of the opening "Moderato" section is incredibly spare and simple, cadences wrongfooting the listener by never quite resolving where you expect. There are oblique glances towards Rachmaninov and Prokofiev, and a darkly witty passage nine minutes in which always reminds me of Jacques Loussier – Schnittke did have a sense of humour. Welser-Möst's strings are barely audible at the close, reduced to what could pass for radio feedback. Good documentation and superb engineering don’t redeem the presentation, however; the CD is flimsily attached to the inside of the floppy front cover like a magazine freebie and the whole package is an awkward size. Can we have the next release from this source in a more sturdy format, please?

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Classical music

Hallé John Adams festival, Bridgewater Hall / RNCM, Manchester review - standing ovations for today's music

From 1980 to 2025 with the West Coast’s pied piper and his eager following

Hallé John Adams festival, Bridgewater Hall / RNCM, Manchester review - standing ovations for today's music

From 1980 to 2025 with the West Coast’s pied piper and his eager following

Kaploukhii, Greenwich Chamber Orchestra, Cutts, St James's Piccadilly review - promising young pianist

A robust and assertive Beethoven concerto suggests a player to follow

Kaploukhii, Greenwich Chamber Orchestra, Cutts, St James's Piccadilly review - promising young pianist

A robust and assertive Beethoven concerto suggests a player to follow

Robin Holloway: Music's Odyssey review - lessons in composition

Broad and idiosyncratic survey of classical music is insightful but slightly indigestible

Robin Holloway: Music's Odyssey review - lessons in composition

Broad and idiosyncratic survey of classical music is insightful but slightly indigestible

Classical CDs: Wolf-pelts, clowns and social realism

British ballet scores, 19th century cello works and contemporary piano etudes

Classical CDs: Wolf-pelts, clowns and social realism

British ballet scores, 19th century cello works and contemporary piano etudes

Bizet in 150th anniversary year: rich and rare French offerings from Palazzetto Bru Zane

Specialists in French romantic music unveil a treasure trove both live and on disc

Bizet in 150th anniversary year: rich and rare French offerings from Palazzetto Bru Zane

Specialists in French romantic music unveil a treasure trove both live and on disc

Scottish Chamber Orchestra, Ibragimova, Queen’s Hall, Edinburgh review - rarities, novelties and drumrolls

A pity the SCO didn't pick a better showcase for a shining guest artist

Scottish Chamber Orchestra, Ibragimova, Queen’s Hall, Edinburgh review - rarities, novelties and drumrolls

A pity the SCO didn't pick a better showcase for a shining guest artist

Kilsby, Parkes, Sinfonia of London, Wilson, Barbican review - string things zing and sing in expert hands

British masterpieces for strings plus other-worldly tenor and horn - and a muscular rarity

Kilsby, Parkes, Sinfonia of London, Wilson, Barbican review - string things zing and sing in expert hands

British masterpieces for strings plus other-worldly tenor and horn - and a muscular rarity

From Historical to Hip-Hop, Classically Black Music Festival, Kings Place review - a cluster of impressive stars for the future

From quasi-Mozartian elegance to the gritty humour of a kitchen inspection

From Historical to Hip-Hop, Classically Black Music Festival, Kings Place review - a cluster of impressive stars for the future

From quasi-Mozartian elegance to the gritty humour of a kitchen inspection

Shibe, LSO, Adès, Barbican review - gaudy and glorious new music alongside serene Sibelius

Adès’s passion makes persuasive case for the music he loves, both new and old

Shibe, LSO, Adès, Barbican review - gaudy and glorious new music alongside serene Sibelius

Adès’s passion makes persuasive case for the music he loves, both new and old

Anja Mittermüller, Richard Fu, Wigmore Hall review - a glorious hall debut

The Austrian mezzo shines - at the age of 22

Anja Mittermüller, Richard Fu, Wigmore Hall review - a glorious hall debut

The Austrian mezzo shines - at the age of 22

First Person: clarinettist Oliver Pashley on the new horizons of The Hermes Experiment's latest album

Compositions by members of this unusual quartet feature for the first time

First Person: clarinettist Oliver Pashley on the new horizons of The Hermes Experiment's latest album

Compositions by members of this unusual quartet feature for the first time

Add comment