Paula Rego, Tate Britain review - the artist's inner landscape like never before | reviews, news & interviews

Paula Rego, Tate Britain review - the artist's inner landscape like never before

Paula Rego, Tate Britain review - the artist's inner landscape like never before

A magnificent retrospective celebrates one of the outstanding artists of her generation

It is conventional for artists to reflect their surroundings, experiences and inspirations, whether this be in a subliminal manner or overtly. But Paula Rego is by no means conventional. She is a rebel, a nonconformist, a freethinker. Rego doesn’t simply reflect the world around her, but soaks it in like an emotional sponge, before squeezing every last feeling out onto the canvas with passion and vigour.

Rego was born in Lisbon, Portugal in 1935, under the Salazar dictatorship, where strong, liberal views were instilled by her father, José Figueiroa Rego, who was a resolute anti-fascist. He encouraged her to question the status quo and think differently, an influence that fuelled all her work as an artist.

Having recognised the confines of living in Portugal, José and Mariade Rego sent their 16-year-old daughter to England, where from 1952-56 she studied at the Slade School of Fine Art. It was here she painted Portrait of José Figueiroa Rego, 1954-5, a standout piece in the first room of Tate’s exhibition. Visceral brushstrokes coat the canvas implying intimate, psychological knowledge of the man, who is in deep thought. Personal and artistic inspirations intertwine, as the piece is reminiscent of Francis Bacon and Lucian Freud, who taught her at the Slade. Rego describes her father as an “immensely kind and liberal man, who tried to give me my freedom".

Having recognised the confines of living in Portugal, José and Mariade Rego sent their 16-year-old daughter to England, where from 1952-56 she studied at the Slade School of Fine Art. It was here she painted Portrait of José Figueiroa Rego, 1954-5, a standout piece in the first room of Tate’s exhibition. Visceral brushstrokes coat the canvas implying intimate, psychological knowledge of the man, who is in deep thought. Personal and artistic inspirations intertwine, as the piece is reminiscent of Francis Bacon and Lucian Freud, who taught her at the Slade. Rego describes her father as an “immensely kind and liberal man, who tried to give me my freedom".

Discussion of politics has never been off limits for Rego; in fact she puts it at the forefront of her work, never shying away from, or censoring her opinions. This is clear in Salazar Vomiting the Homeland, 1960, where she paints an abstracted, yet gruesome, picture in response to the repression and enforced austerity of Salazar’s regime. On the right, the fascist leader is small, ugly, messily being sick, while in the centre a larger figure representing a woman stands tall covered in dried blood. Forget subtlety, Rego is practising her freedom of expression to the fullest. Because of the abstraction of the image, the title plays a huge role in making the artwork overtly political. This is also the case for pieces, such as When we had a house in the country we’d throw marvellous parties and then we’d go out and shoot black people, 1961. She makes sure that there is no confusion about the politics of her images.

Growing up under this regime, Rego became aware of many forms of abuse, notably violence against women, who were treated as the property of their fathers and husbands. She describes hearing the screams of a woman being beaten by her miller husband, close to the farm where she lived and being disturbed that no one came to help her. As an artist, she has continued to showcase and question injustices against women in her work, whether this be domestic abuse, sexual liberation or abortion rights. Bride, 1994, is a striking, large-scale, pastel depiction of a woman on her wedding night from the artist’s well known Dog Woman series. Looking directly into the eyes of the viewer, the bride appears strong, but not happy. This contrasts traditional portrayals of brides throughout art history, where the women are sweet, innocent and apparently content to be the “property” of a man. Compared to La Velata, 1515, by Raphael, for example, it depicts a more powerful story; Rego, as a woman artist, has taken control of how her sex is portrayed.

Throughout her life, Rego has dealt with difficult experiences and emotions (main picture: The Little Murderess, 1987). She has used these to drive her artwork, particularly in her Girl and Dog series, which exposes how she felt looking after her unwell husband, Victor Willing, in the last years of his life. Rego met Victor at the Slade in 1952 and later they married and had three children together. Not long afterwards, he fell ill with multiple sclerosis and began a decline that lasted 15 years. Girl Lifting her Skirt to a Dog, 1986, is an arresting portrayal of Rego’s sexual and general frustration. Representing Rego, the girl appears determined yet distressed, wanting satisfaction that she knows she will not get. The dog, representing her husband, looks back at her in a helpless, wide-eyed manner. His illness is affecting her, but he cannot control this. Nothing she can do will change his situation – she is the helpless one.

Throughout her life, Rego has dealt with difficult experiences and emotions (main picture: The Little Murderess, 1987). She has used these to drive her artwork, particularly in her Girl and Dog series, which exposes how she felt looking after her unwell husband, Victor Willing, in the last years of his life. Rego met Victor at the Slade in 1952 and later they married and had three children together. Not long afterwards, he fell ill with multiple sclerosis and began a decline that lasted 15 years. Girl Lifting her Skirt to a Dog, 1986, is an arresting portrayal of Rego’s sexual and general frustration. Representing Rego, the girl appears determined yet distressed, wanting satisfaction that she knows she will not get. The dog, representing her husband, looks back at her in a helpless, wide-eyed manner. His illness is affecting her, but he cannot control this. Nothing she can do will change his situation – she is the helpless one.

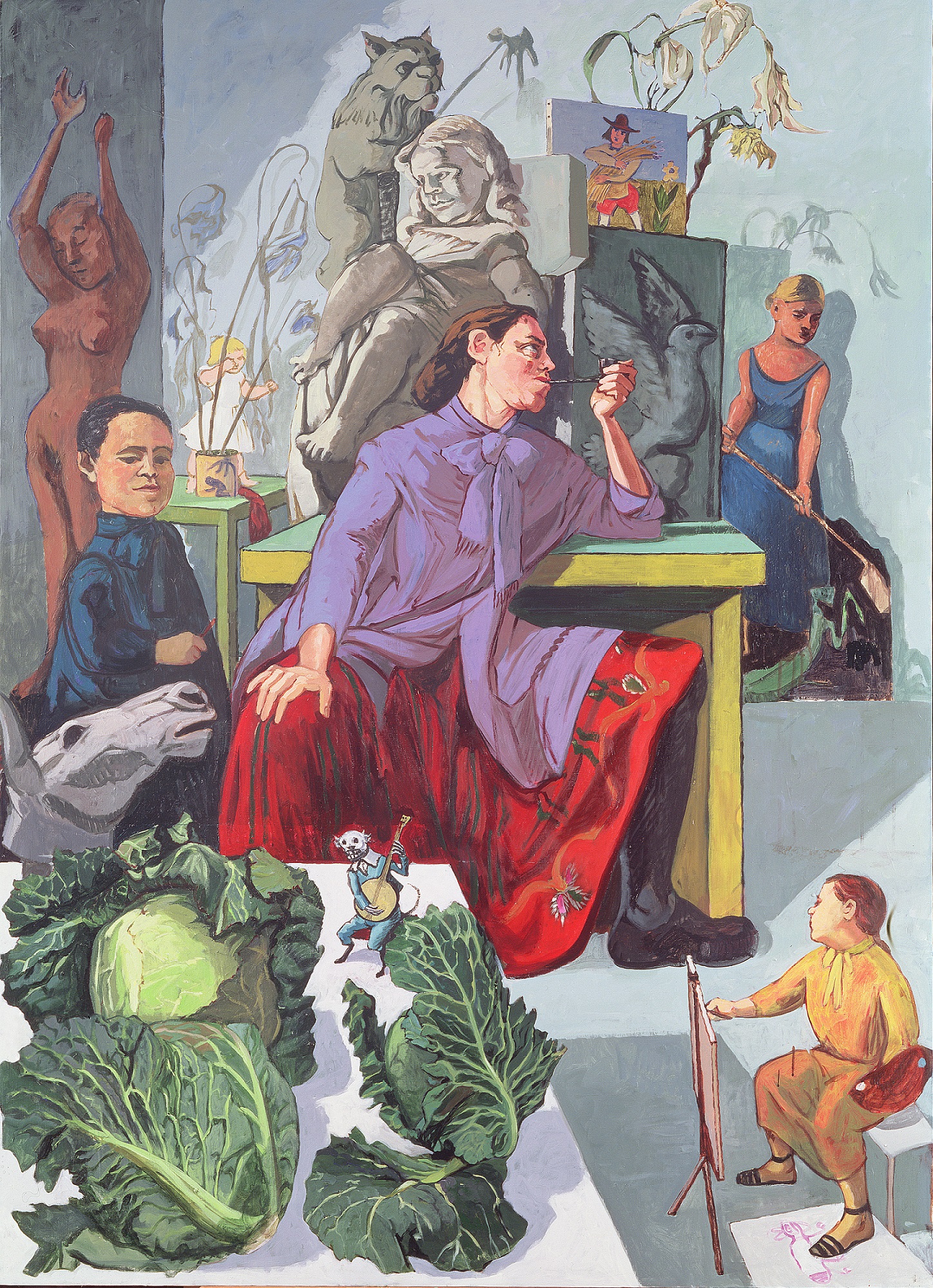

One benefit of a large and comprehensive retrospective is that viewers get a well-rounded sense of the artist’s growth. In Rego’s case, her development in style is clear. Two artworks which perfectly illustrate this are two self-portraits, Self-Portrait in Red, 1966 (pictured above right), and The Artist in Her Studio, 1993 (pictured above left). Self-Portrait in Red is a surreal, symbolic collage which depicts the artist as a small girl; it is a style that is difficult to understand without the help of a title and supporting text. Although her views were strong, Rego was tackling reality by creating a fantasy, expressing herself in a more coded, inexplicit way. However, by the time she painted The Artist in Her Studio, her style had become realistic and concrete, presenting us with a version of reality that we recognise and immediately understand. This is also the case for other pieces with difficult subject matter, such as abortion, where she is not afraid to paint all the grim details – Rego and her girls look us in the eye and tell us their story unapologetically.

This exhibition takes you on multiple journeys: personal experience, political rebellion, social injustice, emotional trauma, artistic development. As an artist, Rego is deep, thought provoking, intelligent and thoroughly important to the art world and its history. As a woman artist, she pushes boundaries and takes control. This unconventional figure deserves to be championed as an outstanding artist of her generation.

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Yoshitomo Nara, Hayward Gallery review - sickeningly cute kids

How to make millions out of kitsch

Yoshitomo Nara, Hayward Gallery review - sickeningly cute kids

How to make millions out of kitsch

Hamad Butt: Apprehensions, Whitechapel Gallery review - cool, calm and potentially lethal

The YBA who didn’t have time to become a household name

Hamad Butt: Apprehensions, Whitechapel Gallery review - cool, calm and potentially lethal

The YBA who didn’t have time to become a household name

Add comment