Chris Ofili, Tate Britain | reviews, news & interviews

Chris Ofili, Tate Britain

Chris Ofili, Tate Britain

Retrospective tracks artist's journey towards Trinidad

Dazzling and surprising, this Tate Britain retrospective by the 1998 Turner Prizewinner Chris Ofili should erase memories of the media sniping about him making money from using the so-called "gimmick" of incorporating elephant turds in his paintings. It will also confirm his status as one of the greatest contemporary British artists.

A chronological journey through his relatively brief career charted from the early 1990s, the exhibition leads visitors along his painting time-line into three final rooms devoted to work produced since he moved to Trinidad in 2005. Astonishingly different and constructed with a new vocabulary and palette, they introduce fresh references which hook, via the landscape and light and local mythologies, deep into his African ancestry.

My first encounter with Chris Ofili’s paintings in the late 1990s left me strangely detached and emotionally confused: impressed by their designs, dazzling colour combinations and detailed crafting, but not convinced they were more than sophisticatedly decorative. But walking through this retrospective, I was entirely convinced by these familiar works with their sequinned outlines of figures and bead-effect dots marking out subjects, densely patterned designs on canvases supported by shiny round elephant turds.

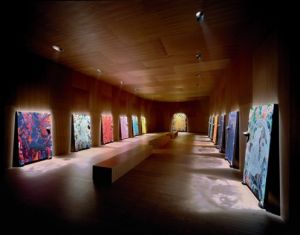

The shit-balls became a signature detail which brought Ofili attention beyond the art world, and provoked accusations that they were a gimmick, but I had been convinced by their subversive presence as they snapped the tolerance of YBA-suspicious tabloids who stuck their knives into the cool, assured African Briton from Manchester. Ofili seemed to thrive on controversy around his work: in 1999, the New York mayor Rudolf Giuliani was appalled up by the "sacrilegious content" of Ofili’s The Holy Virgin Mary posed pregnant against a backdrop interspersed with close-ups of women’s genitalia cut from men’s porn magazines, and he blocked the planned exhibition at Brooklyn Art Museum. The UK tabloids were gleeful, in 2005, when the Tate Gallery purchased a set of paintings entitled The Upper Room from Ofili while he was still a trustee (pictured above, courtesy of Victoria Miro Gallery. Photo Stephen White © Chris Ofili).

The shit-balls became a signature detail which brought Ofili attention beyond the art world, and provoked accusations that they were a gimmick, but I had been convinced by their subversive presence as they snapped the tolerance of YBA-suspicious tabloids who stuck their knives into the cool, assured African Briton from Manchester. Ofili seemed to thrive on controversy around his work: in 1999, the New York mayor Rudolf Giuliani was appalled up by the "sacrilegious content" of Ofili’s The Holy Virgin Mary posed pregnant against a backdrop interspersed with close-ups of women’s genitalia cut from men’s porn magazines, and he blocked the planned exhibition at Brooklyn Art Museum. The UK tabloids were gleeful, in 2005, when the Tate Gallery purchased a set of paintings entitled The Upper Room from Ofili while he was still a trustee (pictured above, courtesy of Victoria Miro Gallery. Photo Stephen White © Chris Ofili).

That widespread criticism was valid; the deal broke rules of trust. The reappearance of The Upper Room (1999-2002) at Tate Britain still induces the same response as when it was constructed by the architect David Adjaye for the Victoria Miró Gallery, in 2005: silent concentration. Adjaye’s wooden installation leads visitors through a narrow, Richard Serra-like tunnel, into a long chapel-gallery. Careful lighting transforms the 13 monkey-god paintings lining the room into stained-glass windows and viewers behave as if they’re in a non-specific holy space. It does indeed create a secularly calming atmosphere. But the experience still leaves me strangely detached towards the macaque monkeys posing with chalices amongst painted patterned veils; they still evoke those exquisite, sophisticated designs incorporated into diaphanous Indian and Balinese fabrics.

Ofili’s early technique of outlining and adorning figures with tiny dotted and beaded patterns resembling Aboriginal Songlines paintings but actually inspired by Zimbabwean artists met during a visit there, include the dazzling Afrodizzia, 1996 (pictured left. Courtesy of Victoria Miro Gallery © Chris Ofili). A magnificent creation, it is built up in layers with bright, often iridescent painted whorls containing the cut-out heads of men with Afros, the surface dotted with dung-balls labelled with map pins spelling the names of eminent black sportsmen, and the whole thing spun into a psychedelic dazzle. It us an early classic. And it emerged, the artist told ICA director Ekow Eshun during their catalogue interview, “Like, bang, there it is. Afro head – celebration of Afrocentricity.” That theme inspired many early works, exhibited in one room, and one interesting piece Shithead, which is not a painting but a shit-ball encased in glass box in a gallery and therefore elevated to the status of objet (pictured below. Courtesy of Victoria Miro Gallery. Photo Todd White Art Photography © Chris Ofili)

Ofili’s early technique of outlining and adorning figures with tiny dotted and beaded patterns resembling Aboriginal Songlines paintings but actually inspired by Zimbabwean artists met during a visit there, include the dazzling Afrodizzia, 1996 (pictured left. Courtesy of Victoria Miro Gallery © Chris Ofili). A magnificent creation, it is built up in layers with bright, often iridescent painted whorls containing the cut-out heads of men with Afros, the surface dotted with dung-balls labelled with map pins spelling the names of eminent black sportsmen, and the whole thing spun into a psychedelic dazzle. It us an early classic. And it emerged, the artist told ICA director Ekow Eshun during their catalogue interview, “Like, bang, there it is. Afro head – celebration of Afrocentricity.” That theme inspired many early works, exhibited in one room, and one interesting piece Shithead, which is not a painting but a shit-ball encased in glass box in a gallery and therefore elevated to the status of objet (pictured below. Courtesy of Victoria Miro Gallery. Photo Todd White Art Photography © Chris Ofili)

Ofili hacked a small gaping mouth into the ball and inserted some baby-teeth, then glued strands of his dreadlocks on top. The result is hauntingly suggestive of a shrunken head, and primal as a voodoo talisman. It reminds me of the fetish objects representing the Afro-Cuban deity Elegua: small, grey granite domes stuck with cowrie shell eyes and mouth, which sell in African fetish markets and botanicas around the diaspora. Latinos in New York place Elegua strategically behind the front door, feed it rum each day, and believe it guards them from dangerous visitors.

Ofili hacked a small gaping mouth into the ball and inserted some baby-teeth, then glued strands of his dreadlocks on top. The result is hauntingly suggestive of a shrunken head, and primal as a voodoo talisman. It reminds me of the fetish objects representing the Afro-Cuban deity Elegua: small, grey granite domes stuck with cowrie shell eyes and mouth, which sell in African fetish markets and botanicas around the diaspora. Latinos in New York place Elegua strategically behind the front door, feed it rum each day, and believe it guards them from dangerous visitors.

Unlike the powerful simplicity of Shithead, Ofili’s paintings require from him almost meditative calm. With early works, he says, he tried “to get as deeply lost as possible in both the process of painting and the painting itself”. It is the same with the late 1990s pencil drawings, created almost obsessively from a myriad tiny heads with huge, stylised Afro halos and linked together by plaited beards to form chains of words and patterns like concrete poetry; perfect still for agit-prop posters.

That layered collaging introduces a comic-book effect used effectively in paintings inspired by Eighties and Nineties funk culture and cult Blaxploitation movies. A first New York trip, in 1994, seems to have concentrated ideas and inspired themes of Blackness and Black identity which introduced new visual references into his work. The Adoration of Captain Shit and the Legend of the Black Stars (1998) is a quintessential showcase of the stereotypical funk pimp character. With his gaudy, blingy jacket, leering lips and women’s hands reaching out to his crutch, it established a style which fitted the time, evoking the trippy cosmology created by George Clinton for his Parliament and Funkadelic songs, and their conversion, visually, into his record sleeve art works.

Ofili maybe adapted their ideas to his own collaging and layering techniques to create similar works including the satirical Pimpin’ Ain’t Easy, a gigantic, smiling phallus whose title is spelled out in pins stuck into dung-balls. Surrounding the gigantic penis are cut-outs of men and women engaged in sexual antics – all elements offering a back-story to today’s explicit hip-hop culture.

Standing apart, No Woman, No Cry (pictured left. Photo Tate © Chris Ofili) is a timelessly beautiful, eloquent work created for Doreen Lawrence after the murder of her son, Stephen. Its crystalline tears streaming down her cheek contain tiny photographs of Stephen, and the lattice of painted "beads" draped across the canvas sets up a divide between subject and viewer suggesting the prison-like state of grief she inhabits.

Standing apart, No Woman, No Cry (pictured left. Photo Tate © Chris Ofili) is a timelessly beautiful, eloquent work created for Doreen Lawrence after the murder of her son, Stephen. Its crystalline tears streaming down her cheek contain tiny photographs of Stephen, and the lattice of painted "beads" draped across the canvas sets up a divide between subject and viewer suggesting the prison-like state of grief she inhabits.

Shortly after The Upper Room success in 2005, Chris Ofili moved to Trinidad, a few years after his Chelsea Art School friend and fellow Victoria Miró artist Peter Doig. "Drink this… let this island medicine intoxicate you. Let the liquor dance a spirit dance in your veins." - the Trinidadian poet Attillah Springer wrote these words in her long poem for the exhibition catalogue. Intoxicated Ofili surely has been, and the stunning new work on show in the final three rooms of the exhibition is evidence. Moving into a tropical climate and an Afro-Caribbean island has inevitably transformed his art – and his lifestyle.

The sounds and smells, local culture and mythologies surround him, and his paintings now come alive from a new palette inspired by the colours of luscious tropical flowers and the blue-blacks nights. Humidity plays havoc with oil paints which sink faster into the canvas, but he seems to have shrugged and let them go their way, appearing thinner and even patchy on the surface of some canvases, often leaving the weave visible and occasional gaps between blocks of colour.

In contrast are the exceptional nocturnal paintings which cover the canvas densely and create astonishing, barely visible effects of night. The blues of these nocturnal paintings, made in the forest, are at the mercy of the moon’s moods. A silver paint layer forms the base for the blue and black acrylics, and builds a magical, dream-like atmosphere which is particularly effective for the forest foliage hanging transluscent against the uniform blueness of the sky.

In the tropics, night drops like a blackout curtain at a prescribed time, changing light into dark within half an hour. When night falls, the other world awakens and that’s when Ofili often takes his paints and walks into the jungle forest to work. And it’s when the douens emerge: female ghouls who shed their skin at nightfall and whisk away children. Douens dance (not exhibited) depicts a scene where a couple dance under a ceiling painted with stars. Douens, writes Atillah Springer, “are now gangsters,” and the name has been transposed from folkloric child killers onto gangstas who kill children with drugs.

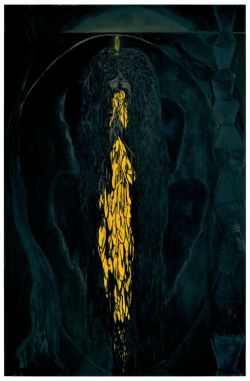

Springer’s line refers to The Healer (pictured below. Courtesy of David Zwirner, New York © Chris Ofili), another ghostly night-bird, depicted in the large, eponymous painting which dominates the exhibition’s final room (it could conceivably apply to the artist at work). A magnificent piece, it is only fully visible when the eyes have adjusted to the painting’s darkness, as if being viewed from within the forest. The Healer, tall and straight as a tree, is enveloped within a sarcophagus-like space and wrapped in dreadlocks which cascade to the ground and have the gnarled texture of bark. The entire scene shares similar tones of black and darkest grey, except the radiant centrepiece of the canvas – flowing like golden lava or one of the waterfalls which have inspired several (unexhibited) paintings - the bright yellow poui flowers which bloom all day and in the morning cover the ground. The Healer gorges orgasmically on fistfuls of them, with eyes closed, and meaning as difficult to see as the man himself.

A different, equally new theme is dancing. The marvellous Dance in Shadow (main picture) possesses an old-fashioned quality drawn from muted-bright colours and almost abstract forms, suggestive of the 1920s Harlem Renaissance styles. All through this final section, Ofili reduces his subjects and their surroundings to simple shapes, and gone is the early decorative adornment. For Dance in Shadow, the simplest palette of flattened purple, gilded orange, intense blacks and blues replaces the jazzy psychedelia of his previous life. The couple dance in silent abandon, her wild African hair and their bodies and clothes merging in colour and form with the massive leaf fronds surrounding them. Central to the scene, her disproportionately large, purple arm describes an abstract curve with the rhythm of a Matisse dancer.

A different, equally new theme is dancing. The marvellous Dance in Shadow (main picture) possesses an old-fashioned quality drawn from muted-bright colours and almost abstract forms, suggestive of the 1920s Harlem Renaissance styles. All through this final section, Ofili reduces his subjects and their surroundings to simple shapes, and gone is the early decorative adornment. For Dance in Shadow, the simplest palette of flattened purple, gilded orange, intense blacks and blues replaces the jazzy psychedelia of his previous life. The couple dance in silent abandon, her wild African hair and their bodies and clothes merging in colour and form with the massive leaf fronds surrounding them. Central to the scene, her disproportionately large, purple arm describes an abstract curve with the rhythm of a Matisse dancer.

These recent, tropical paintings close off an extraordinary exhibition, and lending the whole collection a perfect, mature shape which reveals the logic of Ofili’s developing explorations of his identity and place. Early Afrocentric themes and the decorative expressions of them seem to be played out and everything reinvented after his arrival in Trinidad. The experience seems to have led him, through the visually over-stimulating surroundings and the folklore he’s engaged with in paintings like The Healer, closer to the mythical "Africa" of his ancestors he’s been seeking. The show's span isn’t vast in time, but in cultural and artistic changes, transformations of themes, techniques and scales, it feels like a life-time’s work.

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

![SEX MONEY RACE RELIGION [2016] by Gilbert and George. Installation shot of Gilbert & George 21ST CENTURY PICTURES Hayward Gallery](https://theartsdesk.com/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail/public/mastimages/Gilbert%20%26%20George_%2021ST%20CENTURY%20PICTURES.%20SEX%20MONEY%20RACE%20RELIGION%20%5B2016%5D.%20Photo_%20Mark%20Blower.%20Courtesy%20of%20the%20Gilbert%20%26%20George%20and%20the%20Hayward%20Gallery._0.jpg?itok=7tVsLyR-) Gilbert & George, 21st Century Pictures, Hayward Gallery review - brash, bright and not so beautiful

The couple's coloured photomontages shout louder than ever, causing sensory overload

Gilbert & George, 21st Century Pictures, Hayward Gallery review - brash, bright and not so beautiful

The couple's coloured photomontages shout louder than ever, causing sensory overload

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Comments

...