Emma Glass: Rest and Be Thankful review – fiction from the paediatric front-line | reviews, news & interviews

Emma Glass: Rest and Be Thankful review – fiction from the paediatric front-line

Emma Glass: Rest and Be Thankful review – fiction from the paediatric front-line

A nurse-writer's artful, visceral story of carers in crisis

How do you prevent a sick baby in a high-care cubicle, his frail chest swamped in secretions, from drowning in his own “loose mucus”? Remove a suction catheter from its wrapping and insert it gently into the tiny mouth. “The whooshing sound of the vacuum sucks up his cracking cry. I flip the switch again and the sound stops. The cry subsides, his breath returns to soft chugs. The oxygen saturations on the monitor rise slightly. I tap his tummy and shush hush him back to sleep.”

Suddenly, we have plunged into a period when hospitals become battle zones, with their personnel seen as shock troops enlisted to resist an all-pervading enemy. Today’s pandemic means that the psychology of medical emergencies now gets to affect (almost) everyone. Even in more normal times, however, front-line treatment may throw crisis after crisis at staff forever just one tough shift away from utter exhaustion of body and spirit alike. And no department of hospital medicine hosts a front-line denser in anguish, terror and last-ditch hope than the paediatric unit.

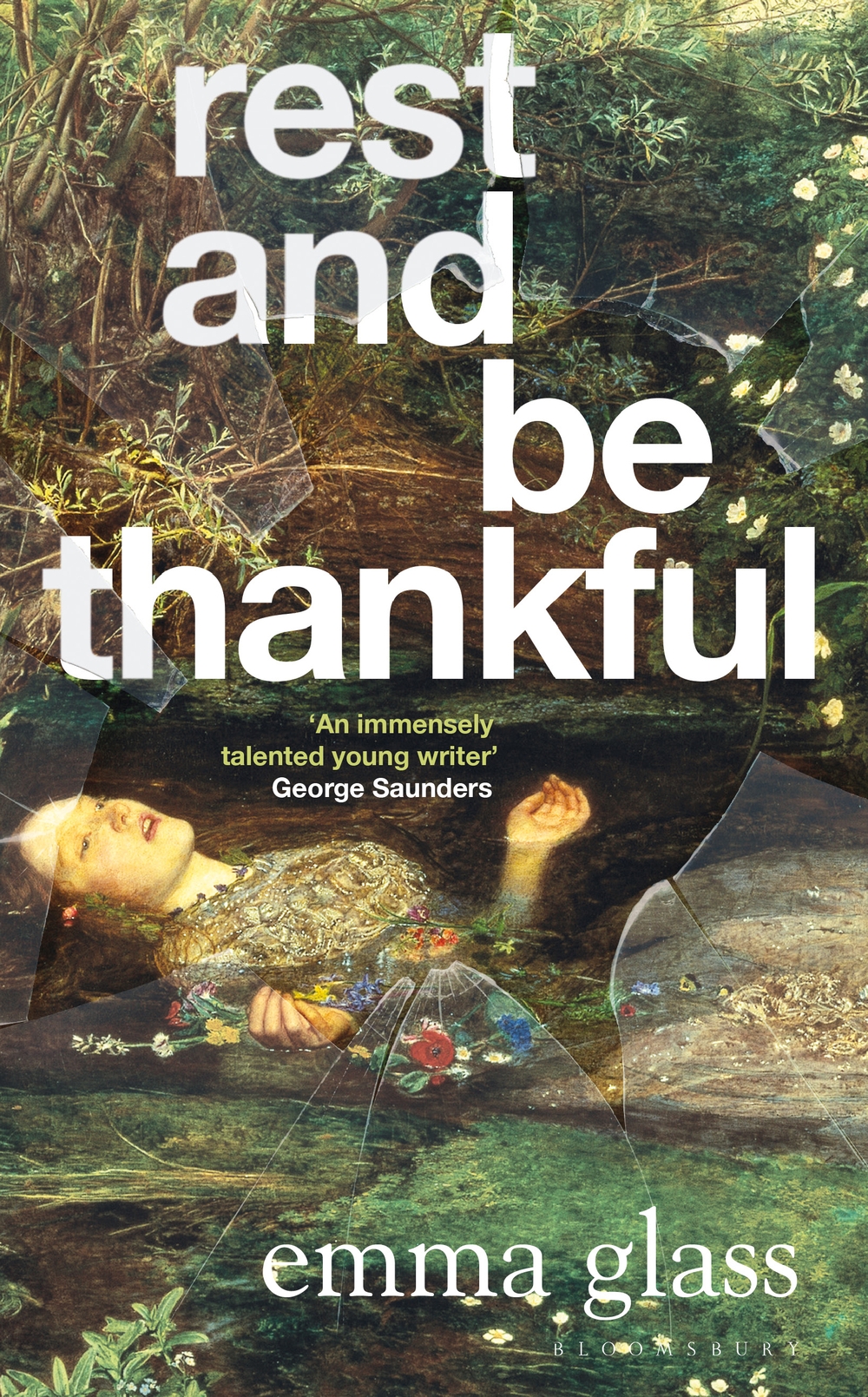

Emma Glass is a richly gifted young novelist – already the author, in 2018, of Peach – who also works as a children’s nurse in London. Whereas her debut burrowed ferociously, but lyrically, into the aftermath of a horrific attack on its young narrator, this second novel unfolds in the professional milieu she knows, and in the driven, haunted minds of the people who sustain it. Doctors have written honoured literature since ancient times; and the modern ranks of medically qualified story-tellers stretch from Somerset Maugham, Anton Chekhov and Mikhail Bulgakov all the way to Adam Kay and Jed (Line of Duty, Bodyguard) Mercurio. Historically, nurse-writers have been a much rarer breed. But the long-overdue respect now accorded to their calling has helped to grow their numbers, with Christie Watson and Nathan Filer two best-selling British authors who have lately moved from the wards to the shelves.

Remarkably, Emma Glass herself still combines nursing with writing. Rest and Be Thankful conveys all the drama, dread, stress and (sometimes) blissful relief of a working life spent in intensive paediatric care. Its galloping pace and breathless immediacy feel deeply, even scarily, authentic. Packed with echoes, assonances and internal rhymes, along with some verbal swerves and twirls that recall the prose work of Dylan Thomas (Glass also comes from Wales), her muscular language throbs with sinewy energy. As the small bodies of their charges struggle against critical illness, in the “spooky and claustrophobic” tech-filled chambers where fragile lives hang by a thread (or a tube), nurse Laura and her colleagues become “cotton buds sucking up the sadness of others, we are saturated, we are saviours. We absorb pain”. However, these wounded, wrung-out healers always fear that “We will wake up one day in a wasteland, surrounded by the crumbling bones of those who loved us and waited for us to love them back.” On every level, Glass counts the steep cost of care, from the marrow-deep tiredness that the paediatric nurses drag through their endless days to the alienation from ordinary relationships that a career built on the brink of tragedy will, inevitably, bring.

Laura, the narrator, and her co-workers fail to save swollen, gasping Danny, whose “two little lungs are rubber balloons never blown”. They coax ailing Buddy towards the longed-for status of “A sick baby on his way to being well”. Rest and Be Thankful meanwhile delivers a string of close-focus, high-impact scenes that blend gnawing tension and surging tenderness. The visceral physicality of Glass’s writing has a shocking sensuousness about it, down to the peculiar texture and odour of the vomit (“sugar and sour milk and nicotine”) that a mother poleaxed by the shock of grief spews onto Laura’s uniform. No wise-cracking, hard-bitten pro from some TV cast of stereotypes, Laura empathises almost to excess with her vulnerable babies and their frantic families. The lure of sacrifice tempts her. In the hospital chapel, after Danny’s death, she prays for him, surrounded by the donated teddy-bears of lost children whose “empty stares cast a spell of sadness over me”.

Laura, the narrator, and her co-workers fail to save swollen, gasping Danny, whose “two little lungs are rubber balloons never blown”. They coax ailing Buddy towards the longed-for status of “A sick baby on his way to being well”. Rest and Be Thankful meanwhile delivers a string of close-focus, high-impact scenes that blend gnawing tension and surging tenderness. The visceral physicality of Glass’s writing has a shocking sensuousness about it, down to the peculiar texture and odour of the vomit (“sugar and sour milk and nicotine”) that a mother poleaxed by the shock of grief spews onto Laura’s uniform. No wise-cracking, hard-bitten pro from some TV cast of stereotypes, Laura empathises almost to excess with her vulnerable babies and their frantic families. The lure of sacrifice tempts her. In the hospital chapel, after Danny’s death, she prays for him, surrounded by the donated teddy-bears of lost children whose “empty stares cast a spell of sadness over me”.

For all the pace and focus of its medical episodes, Rest and Be Thankful amounts to more than a semi-documentary slice of acute-care life. We glimpse Laura’s broken relationship with the cold boyfriend who has ceased to love her; we experience her nightmares of drowning and falling, “lungs bursting… everything hurting”; we share the visions of eerie, spectral figures that flit across her sleep-deprived sight, like “blackness in my peripheral vision”. This short, fierce and immersive novel dips almost into Gothic territory at its close. Some readers may find the denouement too abrupt, even sensational. The sheer intensity of its clinical passages mean that Glass’s narrative, just like her nurses, risks an early burn-out. Some aspects of Laura’s story remain as shadowy as the ghostly apparitions conjured by her weary mind’s eye. Yet the paediatric unit’s relentless cycle of “fresh sickness, old sadness” drives her writing from one pulse-racing peak to another. At its height, Glass’s battlefield prose calls to mind not so much a hospital soap as the literature of the trenches, the dugout and hand-to-hand combat, from the Somme to Vietnam. This, though, is a trauma-generating war on death and despair fought for us in every city, every day.

- Reast and Be Thankful by Emma Glass (Bloomsbury, £12.99)

- Read more book reviews on theartsdesk

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Books

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Thomas Pynchon - Shadow Ticket review - Pulp Diction

Thomas Pynchon's latest (and possibly last) book is fun - for a while

Thomas Pynchon - Shadow Ticket review - Pulp Diction

Thomas Pynchon's latest (and possibly last) book is fun - for a while

Justin Lewis: Into the Groove review - fun and fact-filled trip through Eighties pop

Month by month journey through a decade gives insights into ordinary people’s lives

Justin Lewis: Into the Groove review - fun and fact-filled trip through Eighties pop

Month by month journey through a decade gives insights into ordinary people’s lives

Joanna Pocock: Greyhound review - on the road again

A writer retraces her steps to furrow a deeper path through modern America

Joanna Pocock: Greyhound review - on the road again

A writer retraces her steps to furrow a deeper path through modern America

Mark Hussey: Mrs Dalloway - Biography of a Novel review - echoes across crises

On the centenary of the work's publication an insightful book shows its prescience

Mark Hussey: Mrs Dalloway - Biography of a Novel review - echoes across crises

On the centenary of the work's publication an insightful book shows its prescience

Frances Wilson: Electric Spark - The Enigma of Muriel Spark review - the matter of fact

Frances Wilson employs her full artistic power to keep pace with Spark’s fantastic and fugitive life

Frances Wilson: Electric Spark - The Enigma of Muriel Spark review - the matter of fact

Frances Wilson employs her full artistic power to keep pace with Spark’s fantastic and fugitive life

Elizabeth Alker: Everything We Do is Music review - Prokofiev goes pop

A compelling journey into a surprising musical kinship

Elizabeth Alker: Everything We Do is Music review - Prokofiev goes pop

A compelling journey into a surprising musical kinship

Natalia Ginzburg: The City and the House review - a dying art

Dick Davis renders this analogue love-letter in polyphonic English

Natalia Ginzburg: The City and the House review - a dying art

Dick Davis renders this analogue love-letter in polyphonic English

Tom Raworth: Cancer review - truthfulness

A 'lost' book reconfirms Raworth’s legacy as one of the great lyric poets

Tom Raworth: Cancer review - truthfulness

A 'lost' book reconfirms Raworth’s legacy as one of the great lyric poets

Ian Leslie: John and Paul - A Love Story in Songs review - help!

Ian Leslie loses himself in amateur psychology, and fatally misreads The Beatles

Ian Leslie: John and Paul - A Love Story in Songs review - help!

Ian Leslie loses himself in amateur psychology, and fatally misreads The Beatles

Samuel Arbesman: The Magic of Code review - the spark ages

A wide-eyed take on our digital world can’t quite dispel the dangers

Samuel Arbesman: The Magic of Code review - the spark ages

A wide-eyed take on our digital world can’t quite dispel the dangers

Zsuzsanna Gahse: Mountainish review - seeking refuge

Notes on danger and dialogue in the shadow of the Swiss Alps

Zsuzsanna Gahse: Mountainish review - seeking refuge

Notes on danger and dialogue in the shadow of the Swiss Alps

Add comment