Marianne and Leonard review - the artist, his muse and collateral damage | reviews, news & interviews

Marianne and Leonard review - the artist, his muse and collateral damage

Marianne and Leonard review - the artist, his muse and collateral damage

Laughing Len's relationship with Marianne Ihlen gets the Nick Broomfield treatment

Nick Broomfield is never shy about inserting himself into his documentaries but here he has good reason: he was, briefly, a lover of Marianne Ihlen, Leonard Cohen’s muse (So Long, Marianne was originally called Come On, Marianne; Bird on the Wire was also inspired by her).

In 1968 Broomfield met her on Hydra, the idyllic Greek island where she and Leonard had shared a house since the early Sixties – she gave him his first acid trip and photographed him the morning after - and although one of her other lovers turned up and Broomfield beat a retreat, they remained friends for years and she stayed with him in Kentish Town and Cardiff.

When she was pregnant with Cohen’s child, she asked Broomfield to drive her to Bath for an abortion. “If anyone deserved to have Leonard’s child, she did,” says Cohen’s friend Aviva Layton. “But you cannot be with Leonard, in that sense.” Not so rewarding, then, being a muse, and free love and the Sixties have a lot to answer for here - but it's still irresistible if you're in the mood for nostalgia.

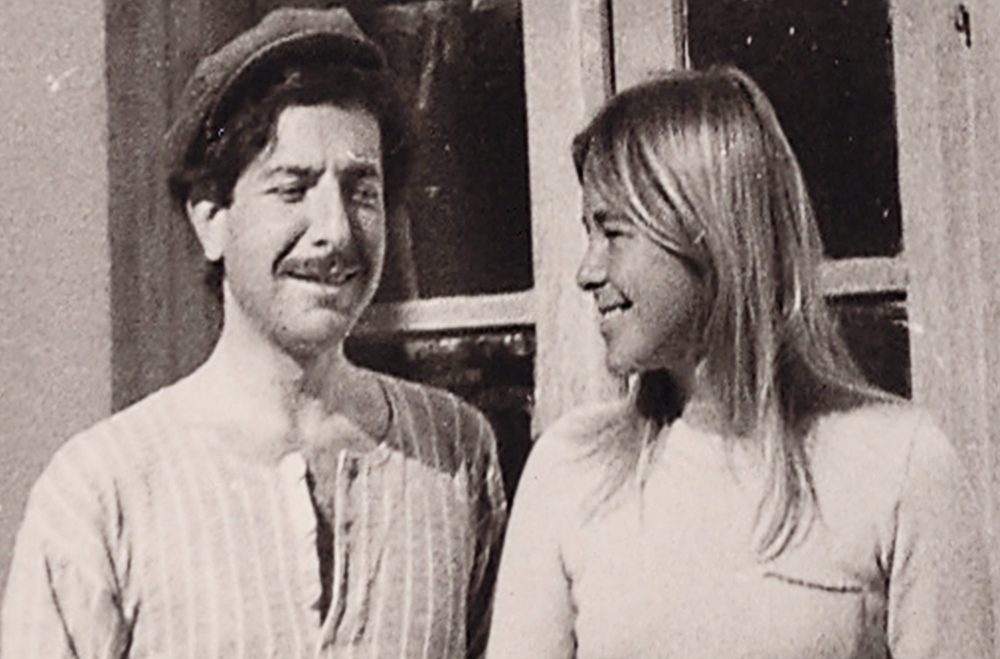

This fascinating, sometimes chronologically confusing, film moves between footage shot by DA Pennebaker in 1967 of Marianne, glowing and golden on sailboats in Hydra with her son Axel from her marriage to the irascible Norwegian writer Axel Jensen, to interviews with Cohen’s Montreal friends, producers and band-members. Not surprisingly, there is more in the archives about Leonard than Marianne (both pictured right, © Aviva Layton).

This fascinating, sometimes chronologically confusing, film moves between footage shot by DA Pennebaker in 1967 of Marianne, glowing and golden on sailboats in Hydra with her son Axel from her marriage to the irascible Norwegian writer Axel Jensen, to interviews with Cohen’s Montreal friends, producers and band-members. Not surprisingly, there is more in the archives about Leonard than Marianne (both pictured right, © Aviva Layton).

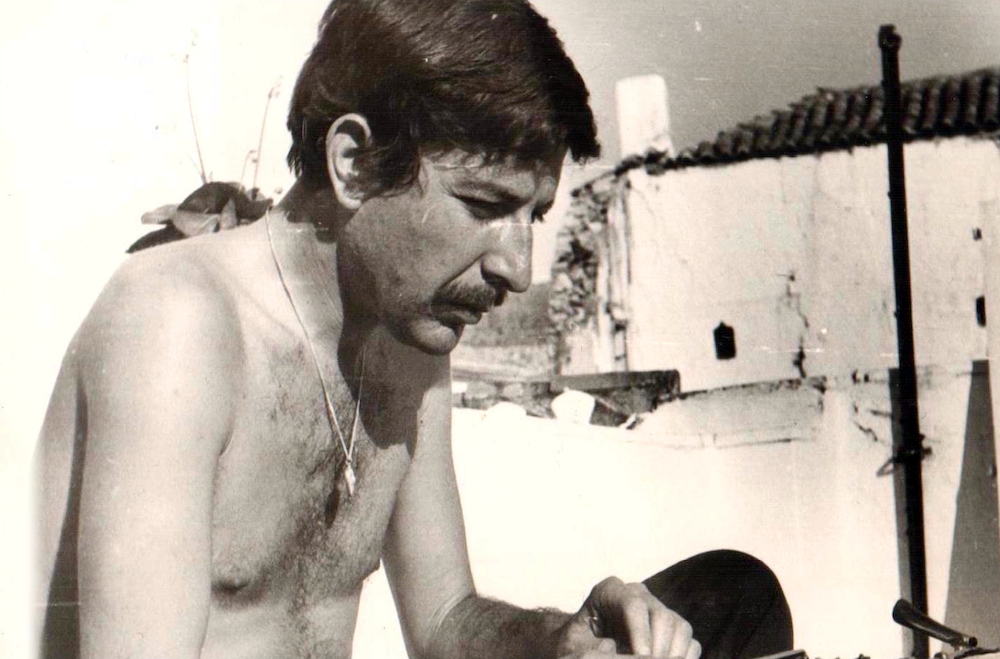

There’s his stage fright when singing Suzanne for the first time with Judy Collins in 1967, which set him on his career as a singer and probably marked the beginning of the end of his relationship with Marianne; reminiscences of making Death of a Ladies’ Man with Phil Spector (“He shoved a revolver into my neck and said, ‘Leonard, I love you.’ I said, ‘I hope you do, Phil’”); scenes at the monastery with his Zen master Roshi; the embezzlement of his money by Kelley Lynch and memories of prodigious drug-taking. He was known as Captain Mandrax (“I was relaxed beyond any reasonable state,”) and wrote Beautiful Losers on speed and LSD in Hydra (pictured below, © Axel Jensen). Then there were the Desert Dust days. “You put a speck on your tongue with a needle and you were gone for 14 hours with no re-entry,” recalls his guitarist Ron Cornelius. “We did that damn Desert Dust 23 nights in a row, playing the Royal Albert Hall,” among other venues.

He was also mad keen on fasting, found a shave mid-concert helped if things weren’t going well, and advised his band members to watch their weight. Neither of them felt that they were beautiful, remembers Marianne. “We’d look in the mirror before we went out and wonder who we were today.”

The dark side of Hydra in the Sixties emerges powerfully. It was awash with drugs and most people, says Helle Goldman, who was a child there, were “irreparably damaged” by its siren call – though not Leonard. Few marriages survived. People were putting LSD in kids’ drinks. Even the donkeys were tripping. Little Axel, Marianne’s son, was a casualty, and has been in institutions most of his adult life.

We hear Marianne’s voice, partly taken from interviews with Kari Hesthamar, her Norwegian biographer. Marianne seems to be reminiscing about being Leonard’s Greek muse, doing the shopping and sitting at his feet while he wrote, while it’s clear from reading Hesthamar’s interview online that she’s actually talking about Jensen. Being Leonard’s muse followed shortly after. Out of the frying-pan into the fire. “She never knew who she was except in relation to them,” says Helle Goldman. To keep up, Marianne said, “I am an artist because life is art and I’m living.”

We hear Marianne’s voice, partly taken from interviews with Kari Hesthamar, her Norwegian biographer. Marianne seems to be reminiscing about being Leonard’s Greek muse, doing the shopping and sitting at his feet while he wrote, while it’s clear from reading Hesthamar’s interview online that she’s actually talking about Jensen. Being Leonard’s muse followed shortly after. Out of the frying-pan into the fire. “She never knew who she was except in relation to them,” says Helle Goldman. To keep up, Marianne said, “I am an artist because life is art and I’m living.”

Lovers came and went all the time. The Sixties were just getting going. Cohen and Ihlen first met when she came back to Hydra from Oslo, where she’d given birth to baby Axel. Immediately, Jensen left her for another woman, and Marianne and Cohen became a couple. “She was beautiful, but she didn’t really enjoy being beautiful until she met Leonard, and he made her love living,” says a friend.

They stayed together on and off for over eight years, keeping a house on Hydra, with Marianne joining him in Montreal and New York, where he holed up at the Chelsea Hotel with Janis Joplin, among others, while she lived in their apartment. It was very hard; she felt suicidal at times. Later Cohen had two children with Suzanne Elrod. “I was obsessed by gaining women’s favours,” he says. “It became the most important thing in my life.”

When Suzanne appeared with her and Cohen’s baby in Hydra, Marianne “calmly packed up and moved out”, went back to Oslo, got herself an ordinary life and remarried. The last scene, in which a dying Marianne hears Leonard’s now famous final message to her, remains very moving. “I’m just a little behind you, close enough to take your hand…Safe travels, old friend. See you down the road.”

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Film

Can I get a Witness? review - time to die before you get old

Ann Marie Fleming directs Sandra Oh in dystopian fantasy that fails to ignite

Can I get a Witness? review - time to die before you get old

Ann Marie Fleming directs Sandra Oh in dystopian fantasy that fails to ignite

Happyend review - the kids are never alright

In this futuristic blackboard jungle everything is a bit too manicured

Happyend review - the kids are never alright

In this futuristic blackboard jungle everything is a bit too manicured

Robert Redford (1936-2025)

The star was more admired within the screen trade than by the critics

Robert Redford (1936-2025)

The star was more admired within the screen trade than by the critics

Blu-ray: The Sons of Great Bear

DEFA's first 'Red Western': a revisionist take on colonial expansion

Blu-ray: The Sons of Great Bear

DEFA's first 'Red Western': a revisionist take on colonial expansion

Spinal Tap II: The End Continues review - comedy rock band fails to revive past glories

Belated satirical sequel runs out of gas

Spinal Tap II: The End Continues review - comedy rock band fails to revive past glories

Belated satirical sequel runs out of gas

Downton Abbey: The Grand Finale review - an attemptedly elegiac final chapter haunted by its past

Noel Coward is a welcome visitor to the insular world of the hit series

Downton Abbey: The Grand Finale review - an attemptedly elegiac final chapter haunted by its past

Noel Coward is a welcome visitor to the insular world of the hit series

Islands review - sunshine noir serves an ace

Sam Riley is the holiday resort tennis pro in over his head

Islands review - sunshine noir serves an ace

Sam Riley is the holiday resort tennis pro in over his head

theartsdesk Q&A: actor Sam Riley on playing a washed-up loner in the thriller 'Islands'

The actor discusses his love of self-destructive characters and the problem with fame

theartsdesk Q&A: actor Sam Riley on playing a washed-up loner in the thriller 'Islands'

The actor discusses his love of self-destructive characters and the problem with fame

Honey Don’t! review - film noir in the bright sun

A Coen brother with a blood-simple gumshoe caper

Honey Don’t! review - film noir in the bright sun

A Coen brother with a blood-simple gumshoe caper

The Courageous review - Ophélia Kolb excels as a single mother on the edge

Jasmin Gordon's directorial debut features strong performances but leaves too much unexplained

The Courageous review - Ophélia Kolb excels as a single mother on the edge

Jasmin Gordon's directorial debut features strong performances but leaves too much unexplained

Blu-ray: The Graduate

Post #MeToo, can Mike Nichols' second feature still lay claim to Classic Film status?

Blu-ray: The Graduate

Post #MeToo, can Mike Nichols' second feature still lay claim to Classic Film status?

Add comment