Yorkshire Sculpture International review - Hepworth and Moore loom large | reviews, news & interviews

Yorkshire Sculpture International review - Hepworth and Moore loom large

Yorkshire Sculpture International review - Hepworth and Moore loom large

A new festival seals Yorkshire's bid to be Britain's home of sculpture

Sculpture is as much a part of Yorkshire as cricket and a decent cup of tea, with the “sculpture triangle”, comprising four prestigious museums and galleries, feeling almost as well-established as the county’s famed rhubarb triangle.

Yorkshire Sculpture International, which runs until 29 September, showcases work new and old against the backdrop of the county’s considerable sculptural heritage, with Barbara Hepworth and Henry Moore, two of Yorkshire’s most illustrious offspring, rarely far from sight or mind. Their commitment to the modernist maxim of “truth to materials” provides a thematic anchor for 18 artists from 12 different countries, united by their interest in exploring the physical and cultural attributes of their chosen materials. New commissions from local and international artists, all at different points in their careers, respond also to a statement by Phyllida Barlow in 2018, that “sculpture is the most anthropological of the artforms.”

A unifying theme is vital for a festival as ambitious as this one, but Barlow’s insistence on sculpture as a human imperative is sufficiently ambiguous that it can accommodate just about anything. At the Henry Moore Institute it embraces the clankingly literal, with Rashid Johnson’s sculptures made from shea butter a striking example of concept triumphing over execution. Shea Butter Three Ways attempts to channel the exotic overtones of this luxury cosmetic ingredient into a broader critique of cultural appropriation and western cultural imperialism. The ideas are good, but the cloying smell is the memory that endures.

A unifying theme is vital for a festival as ambitious as this one, but Barlow’s insistence on sculpture as a human imperative is sufficiently ambiguous that it can accommodate just about anything. At the Henry Moore Institute it embraces the clankingly literal, with Rashid Johnson’s sculptures made from shea butter a striking example of concept triumphing over execution. Shea Butter Three Ways attempts to channel the exotic overtones of this luxury cosmetic ingredient into a broader critique of cultural appropriation and western cultural imperialism. The ideas are good, but the cloying smell is the memory that endures.

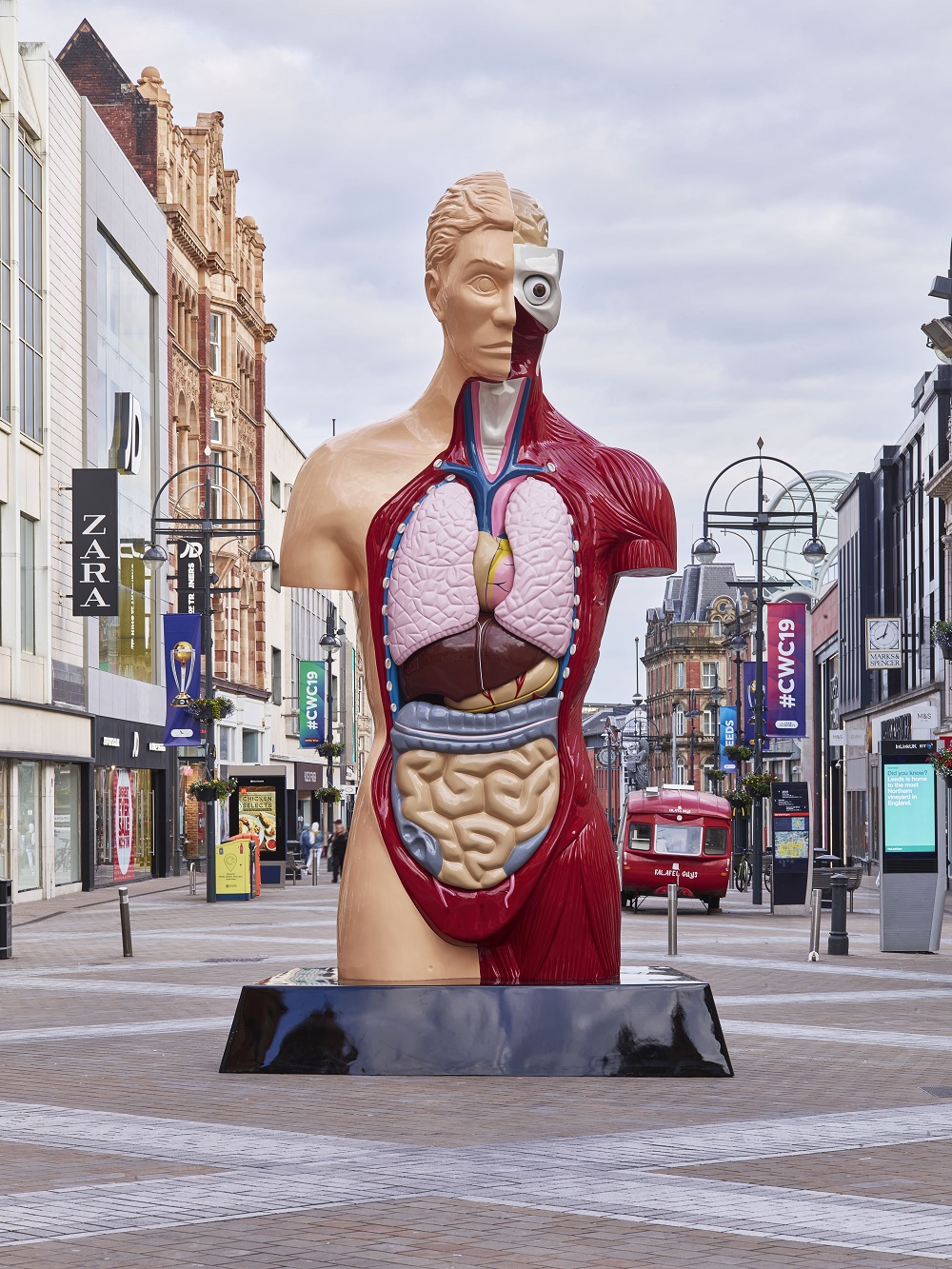

In Leeds and Wakefield city centres, Barlow’s statement might well have provided an opportunity – sadly wasted – for a re-evaluation of public sculpture and its role. Instead Leeds city centre hosts a self-serving homage to another of Yorkshire’s sons, Damien Hirst. Hymn, 1995-2005 (Pictured above right), a giant anatomical model in playschool colours towers over the city’s main shopping street, while inside the elegant Victoria Arcade, something similar bares its organs, as neatly packed and decorative as if they had been parceled up in one of the chichi boutiques nearby.

In Wakefield city centre, Receiver by Huma Bhabha is another dispiriting addition, the more so perhaps because it was specially commissioned. Vaguely humanoid, archly naive, the piece is an artist’s inadequate internal dialogue located in a civic space in a way that shows an extraordinary lack of judgement by both artist and curator. The piece shows no empathy with its location in the city’s fine and dignified square, eliciting well-deserved snorts of derision from passing youth on BMX’s.

If misplaced self-importance is the scourge of public sculpture, self-searching work by west Yorkshire artist Rosanne Robertson brings insight and feeling to big topics. Her casts of rock formations, made on long walks in the countryside near her studio in Hebden Bridge, test the natural states of fluidity and solidity with dedication and originality. For her, these interrogations serves as a means to consider the nature of gender and sexuality: beautiful to look at, sensitive and responsive to the artistic antecedents that surround it in the gallery at Hepworth Wakefield, Robertson’s work combines sculpture and performance in works that are both personal and universal.

In a similar vein, Jamaican-Canadian sculptor Tau Lewis’s work is infused with the power of memory. Pieced together from fabrics collected from different places and people, Lewis’s handsewn sculptures of sea creatures and others are envisaged as reincarnations of victims of the slave trade, lost at sea but perpetuated through private and public acts of remembrance (Pictured above: Tau Lewis, installation image).

In a similar vein, Jamaican-Canadian sculptor Tau Lewis’s work is infused with the power of memory. Pieced together from fabrics collected from different places and people, Lewis’s handsewn sculptures of sea creatures and others are envisaged as reincarnations of victims of the slave trade, lost at sea but perpetuated through private and public acts of remembrance (Pictured above: Tau Lewis, installation image).

The highlight of the offering from the Yorkshire Sculpture Park, and perhaps of the festival overall, is an exhibition dedicated to David Smith (1906-1965), an American sculptor little known outside the USA, with few works in European collections. Though he died very young, he was prolific, and sculptures dating from 1932 until his death seen both outside and in, present a sustained dialogue with sculptural developments of the 20th century.

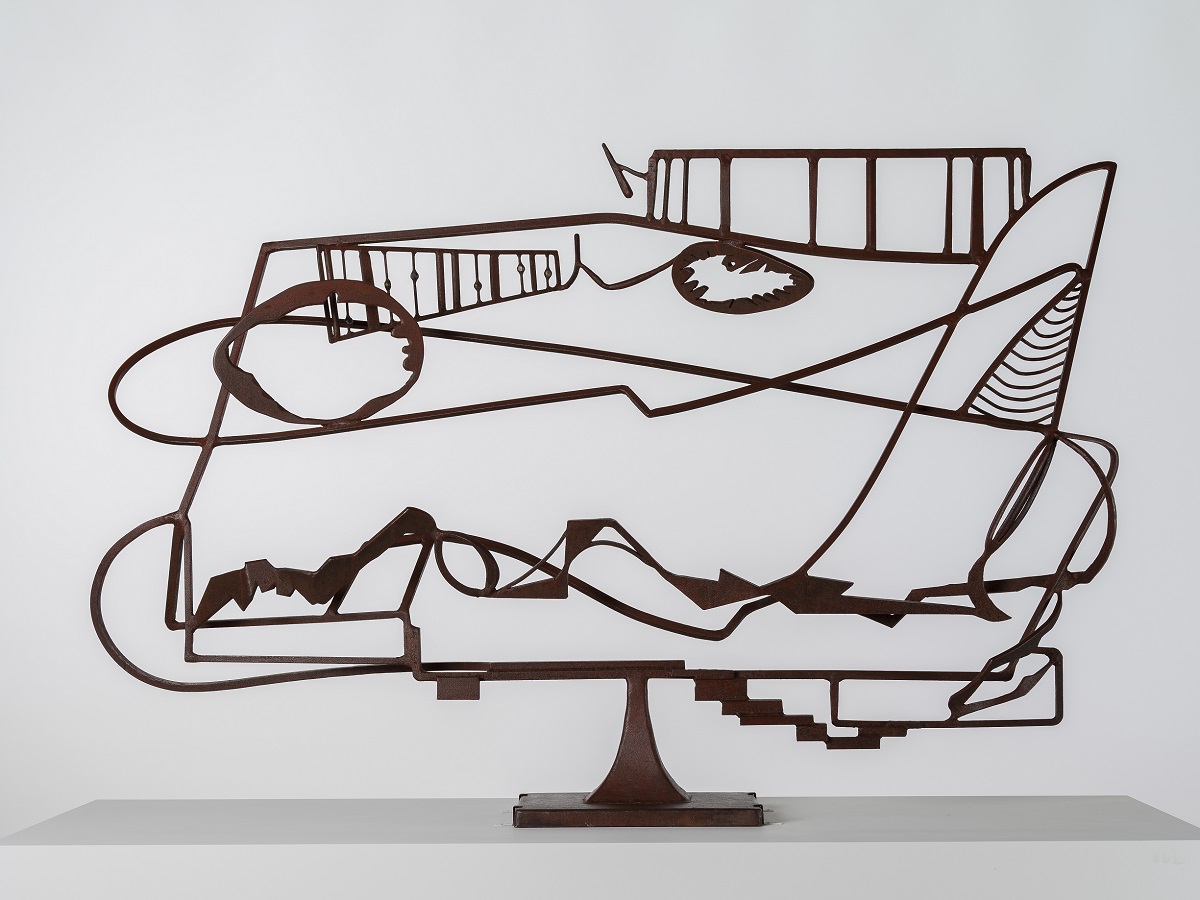

Though Smith can clearly be seen responding to surrealism and kinetic art, for example, it was industrial practices rather than artistic ones that motivated him in the first place. Works from the 1930s and 1940s recall the surrealist constructions of Giacometti, the erotic casts of Duchamp and Louise Bourgeois’s cells, while a piece such as Hudson River Landscape, 1951 (Pictured below), a drawing in metal, relates to the work of his friend Alexander Calder.

In his Medals for Dishonor series, 1939, Smith’s antecedents reach back still further. The series of 15 large scale reliefs recall Renaissance medals, their theme of protest against the horrors of war echoing Goya’s print series, The Disasters of War, 1810-20

In his Medals for Dishonor series, 1939, Smith’s antecedents reach back still further. The series of 15 large scale reliefs recall Renaissance medals, their theme of protest against the horrors of war echoing Goya’s print series, The Disasters of War, 1810-20

Much as fine art provides an intellectual and formal backdrop for Smith’s work, his training as a welder was every bit as influential, a stint at the Studebacker car factory while a student proving formative. A decade or so later, in 1934, Smith rented workspace at the Terminal Iron Works in Brooklyn, so that he was in the remarkable and surely at that time unique position of prdoucing sculptures surrounded by industrial metalworkers.

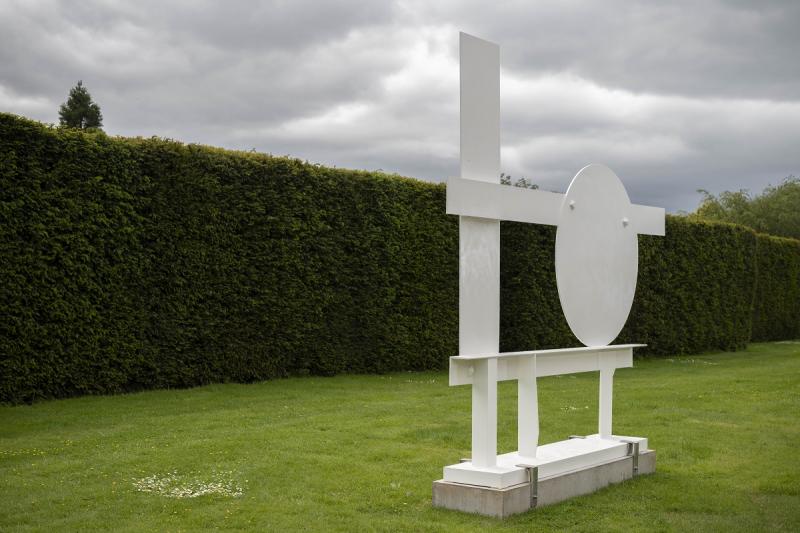

Works from the 1950s and 1960s combine an industrial aesthetic with fields of colour reminiscent of the paintings of that era. In fact, Smith’s work often challenges the very fundamentals of sculpture itself, insisting on flatness and rejecting mass and volume, traditionally the very essence of sculpture (Main picture: Primo Piano III, 1962).

Long-awaited, difficult to stage, and including the rare chance to see Smith’s sculptures out of doors, this exhibition is by far and away the high point of the inaugural Yorkshire Sculpture Festival, and a reason to go in itself. Smith’s works add a further, enlivening dimension to the possibly rather overawing dual presence of Hepworth and Moore. Along with an impressive outreach project that is not only supporting early careers of promising young artists like Roseanne Robertson, but also introducing school children to sculpture, this is what will be remembered from this first edition of a festival that has every reason to grow into an annual monument.

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Photo Oxford 2025 review - photography all over the town

At last, a UK festival that takes photography seriously

Photo Oxford 2025 review - photography all over the town

At last, a UK festival that takes photography seriously

![SEX MONEY RACE RELIGION [2016] by Gilbert and George. Installation shot of Gilbert & George 21ST CENTURY PICTURES Hayward Gallery](https://theartsdesk.com/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail/public/mastimages/Gilbert%20%26%20George_%2021ST%20CENTURY%20PICTURES.%20SEX%20MONEY%20RACE%20RELIGION%20%5B2016%5D.%20Photo_%20Mark%20Blower.%20Courtesy%20of%20the%20Gilbert%20%26%20George%20and%20the%20Hayward%20Gallery._0.jpg?itok=7tVsLyR-) Gilbert & George, 21st Century Pictures, Hayward Gallery review - brash, bright and not so beautiful

The couple's coloured photomontages shout louder than ever, causing sensory overload

Gilbert & George, 21st Century Pictures, Hayward Gallery review - brash, bright and not so beautiful

The couple's coloured photomontages shout louder than ever, causing sensory overload

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Add comment