Hough, Hallé, Elder, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - film music flows | reviews, news & interviews

Hough, Hallé, Elder, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - film music flows

Hough, Hallé, Elder, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - film music flows

A symphony of icy wastes finds new life … and contrasts

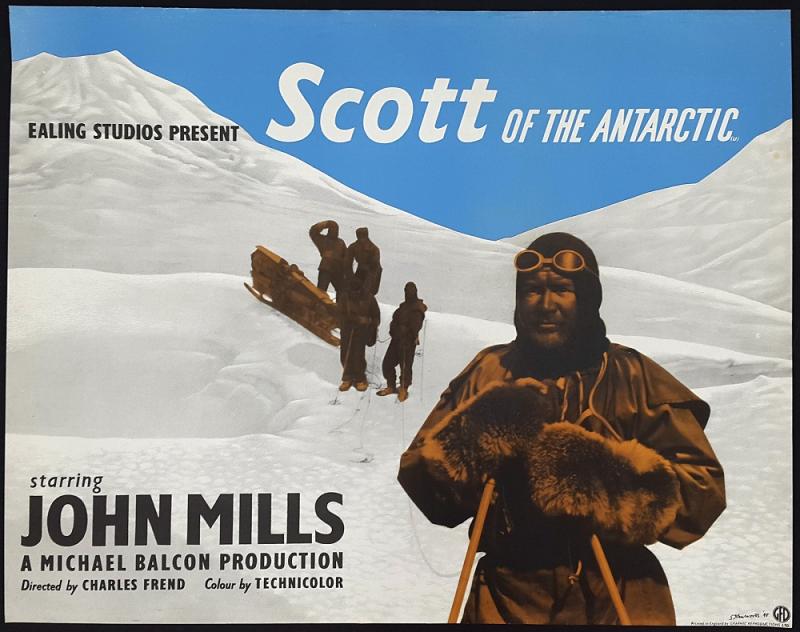

No one worried about melting icecaps and homeless penguins when Vaughan Williams wrote his score for the film Scott of the Antarctic around 70 years ago. (They do now, as a new music theatre piece by Laura Bowler to be premiered by Manchester Camerata next week will show). It was the challenge of the frozen continent and a heroic effort to reach its heart that counted.

The film, starring John Mills, tells the story of Captain Robert Scott’s expedition to the South Pole in 1912, which ended in the deaths of all his team. Vaughan Williams provided music depicting tragedy amid the icy wastes with great vividness, and he extracted much of it to make his Seventh Symphony, the Sinfonia Antartica [sic], which followed in 1953. It’s part of the Hallé’s heritage, as they gave its first performance, under Barbirolli, in Manchester, and, almost on the button of that day 65 years ago, they played it for the man often seen as his true successor in our day, Sir Mark Elder.

I wasn’t old enough to witness that first performance in 1953, though I do remember the Coronation later the same year, with its rousing setting of the Old Hundredth psalm tune provided by the same octogenarian composer. His signature use of sequential triads and big, bold themes is there in the seventh symphony, as is also his ear for tuned percussion (celesta, glockenspiel, vibraphone and xylophone all employed to create atmospheric colours in the orchestra) and his smooth writing for voices – there’s a wordless women’s chorus and a soprano soloist (Sophie Bevan, singing nobly though unseen) whom Sir Mark placed out of sight, along with the wind machine, the better to evoke a sense of distance and eerie remoteness.

There’s powerful writing for brass – powerfully delivered by the Hallé players alongside drum rumbles from their colleagues in the percussion – and in the big central movement, with scary crescendos, the reedy full chorus of the Bridgewater Hall’s organ was added to the sonic mix.

There’s powerful writing for brass – powerfully delivered by the Hallé players alongside drum rumbles from their colleagues in the percussion – and in the big central movement, with scary crescendos, the reedy full chorus of the Bridgewater Hall’s organ was added to the sonic mix.

It all worked very well indeed. The music remains filmic, because its "symphonic" structure relies mainly on a return in the final movement to the thematic material and soundworld of the opening one. But Sir Mark endowed that reprise with considerable dynamic charge, making it the emotional climax of the work as it was undoubtedly meant to be … and moving to a gaspingly drawn-out final niente as the symphony, like its subjects, finally expires. The first part of the concert had been a bright and brilliant contrast of French music. Berlioz’s Benvenuto Cellini Overture swept into life with a splendid attack and glorious string tone for its big opening theme, no skimping on the big-drum-cymbal crashes, some telling rubato in its tenderer moments (and lovely oboe playing from Stéphane Rancourt), and a great animato leading to its brassy culmination.

Then there was Saint-Saëns’ Piano Concerto No. 5, with Stephen Hough (pictured above by Sim Canetty-Clarke) the soloist. It’s called the "Egyptian" concerto because it was written mainly on a winter holiday in Luxor and has a simple tune in its middle movement apparently borrowed from the singing of a Nile boatman. But Saint-Saëns was too much a Frenchman not to keep to traditional form, European cool and elegant decoration in his writing, and even when he uses "eastern" melodic inflexions he westernises their presentation pretty thoroughly.

Stephen Hough gracefully drew every bit of poetry there was from the somewhat workaday themes of the opening – and found drama a-plenty in his solo role – and ended the concerto with glitter and aplomb in its helter-skelter finale. In between there are passages of "mysterious East" effects that would not have disgraced a film score themselves, had David Lean been around to make use of them. All très exotique and beautifully played – as was the little encore from the soloist, of Debussy’s La fille aux cheveux de lin from his first book of Preludes.

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Classical music

Presteigne Festival 2025 review - new music is centre stage in the Welsh Marches

Music by 30 living composers, with Eleanor Alberga topping the bill

Presteigne Festival 2025 review - new music is centre stage in the Welsh Marches

Music by 30 living composers, with Eleanor Alberga topping the bill

Lammermuir Festival 2025 review - music with soul from the heart of East Lothian

Baroque splendour, and chamber-ensemble drama, amid history-haunted lands

Lammermuir Festival 2025 review - music with soul from the heart of East Lothian

Baroque splendour, and chamber-ensemble drama, amid history-haunted lands

BBC Proms: Steinbacher, RPO, Petrenko / Sternath, BBCSO, Oramo review - double-bill mixed bag

Young pianist shines in Grieg but Bliss’s portentous cantata disappoints

BBC Proms: Steinbacher, RPO, Petrenko / Sternath, BBCSO, Oramo review - double-bill mixed bag

Young pianist shines in Grieg but Bliss’s portentous cantata disappoints

theartsdesk at the Lahti Sibelius Festival - early epics by the Finnish master in context

Finnish heroes meet their Austro-German counterparts in breathtaking interpretations

theartsdesk at the Lahti Sibelius Festival - early epics by the Finnish master in context

Finnish heroes meet their Austro-German counterparts in breathtaking interpretations

Classical CDs: Sleigh rides, pancakes and cigars

Two big boxes, plus new music for brass and a pair of clarinet concertos

Classical CDs: Sleigh rides, pancakes and cigars

Two big boxes, plus new music for brass and a pair of clarinet concertos

Waley-Cohen, Manchester Camerata, Pether, Whitworth Art Gallery, Manchester review - premiere of no ordinary violin concerto

Images of maternal care inspired by Hepworth and played in a gallery setting

Waley-Cohen, Manchester Camerata, Pether, Whitworth Art Gallery, Manchester review - premiere of no ordinary violin concerto

Images of maternal care inspired by Hepworth and played in a gallery setting

BBC Proms: Barruk, Norwegian Chamber Orchestra, Kuusisto review - vague incantations, precise laments

First-half mix of Sámi songs and string things falters, but Shostakovich scours the soul

BBC Proms: Barruk, Norwegian Chamber Orchestra, Kuusisto review - vague incantations, precise laments

First-half mix of Sámi songs and string things falters, but Shostakovich scours the soul

BBC Proms: Alexander’s Feast, Irish Baroque Orchestra, Whelan review - rapturous Handel fills the space

Pure joy, with a touch of introspection, from a great ensemble and three superb soloists

BBC Proms: Alexander’s Feast, Irish Baroque Orchestra, Whelan review - rapturous Handel fills the space

Pure joy, with a touch of introspection, from a great ensemble and three superb soloists

BBC Proms: Moore, LSO, Bancroft review - the freshness of morning wind and brass

English concert band music...and an outlier

BBC Proms: Moore, LSO, Bancroft review - the freshness of morning wind and brass

English concert band music...and an outlier

Willis-Sørensen, Ukrainian Freedom Orchestra, Wilson, Cadogan Hall review - romantic resilience

Passion, and polish, from Kyiv's musical warriors

Willis-Sørensen, Ukrainian Freedom Orchestra, Wilson, Cadogan Hall review - romantic resilience

Passion, and polish, from Kyiv's musical warriors

BBC Proms: Faust, Gewandhausorchester Leipzig, Nelsons review - grace, then grandeur

A great fiddler lightens a dense orchestral palette

BBC Proms: Faust, Gewandhausorchester Leipzig, Nelsons review - grace, then grandeur

A great fiddler lightens a dense orchestral palette

BBC Proms: Jansen, Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, Mäkelä review - confirming a phenomenon

Second Prom of a great orchestra and chief conductor in waiting never puts a foot wrong

BBC Proms: Jansen, Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, Mäkelä review - confirming a phenomenon

Second Prom of a great orchestra and chief conductor in waiting never puts a foot wrong

Add comment