Blu-ray: Henri-Georges Clouzot's Inferno | reviews, news & interviews

Blu-ray: Henri-Georges Clouzot's Inferno

Blu-ray: Henri-Georges Clouzot's Inferno

Clouzot's famously unfinished film, dissected with affection

Watching what remains of Henri-Georges Clouzot’s Inferno (L’Enfer) serves to remind us just how good his earlier work was. Inferno marked the beginning of the end, its shambolic production beginning Clouzot’s descent into obscurity.

The hugely anticipated Inferno was started in 1964, four years after Clouzot’s previous film, the Brigitte Bardo-starrer La vérité, which had been a huge box-office success. What was potentially an intimate thriller about a jealous husband and his younger wife became a casualty of directorial hubris. Columbia Pictures recklessly gave Clouzot an unlimited budget, allowing him to hire three crews and 150 technical staff. Meticulously detailed storyboards were drawn up, with colour-coded notes signalling levels of characters’ emotional stress. Weeks were spent creating eye-popping test footage intended to suggest the husband’s mental collapse.

These sequences make the documentary mandatory viewing, a parade of unhinged psychedelic visuals which enthral as much as they bewilder. We get backwards shots of a luminous Romy Schneider (pictured right) exhaling smoke, and extraordinary footage of her and co-star Serge Reggiani illuminated with rotating lights, their faces seemingly melting and reassembling. Schneider even gets to explore the erotic potential of a Slinky. Leading avant-garde composers assisted with the sound design, and Clouzot’s immaculate graphic notation is a joy to behold.

These sequences make the documentary mandatory viewing, a parade of unhinged psychedelic visuals which enthral as much as they bewilder. We get backwards shots of a luminous Romy Schneider (pictured right) exhaling smoke, and extraordinary footage of her and co-star Serge Reggiani illuminated with rotating lights, their faces seemingly melting and reassembling. Schneider even gets to explore the erotic potential of a Slinky. Leading avant-garde composers assisted with the sound design, and Clouzot’s immaculate graphic notation is a joy to behold.

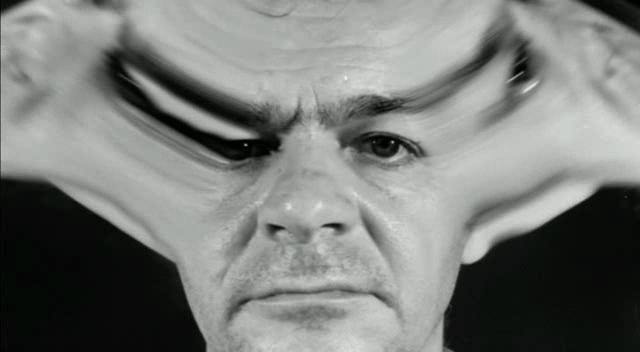

Exterior scenes on a lake would have had their colours reversed, turning the water blood-red – meaning that the actors had to wear blue make-up and lipstick. You sense that the famously well-organised Clouzot was out of his depth. One collaborator recalls the director seeming “a bit Hollywood”, lamenting that “he used to be so efficient.” It’s a miracle that the collapse didn’t come sooner: poor Reggiani (pictured, distorted, below left), presumably exhausted after being made to run for miles each day in blazing heat, exited after a few weeks, allegedly suffering from "Maltese fever". Clouzot vainly tried to secure a replacement, shooting endless retakes in the knowledge that the lake was about to be drained for a hydroelectric scheme. The final blow came when he was hospitalised with a severe heart attack.

The rushes were seized by the insurers, passing to the French National Archives in the 1970s. Clouzot’s career never recovered; a series of documentaries made with conductor Herbert von Karajan and 1968’s La prisonnière were all he produced before his death in 1977. It’s a sorry tale, but Inferno’s fate feels somehow right. What’s described as “the sort of film that could have been shot in eight weeks” would more likely have been a heroic flop, Clouzot’s colourful experimental material at odds with his earthy subject matter.

The rushes were seized by the insurers, passing to the French National Archives in the 1970s. Clouzot’s career never recovered; a series of documentaries made with conductor Herbert von Karajan and 1968’s La prisonnière were all he produced before his death in 1977. It’s a sorry tale, but Inferno’s fate feels somehow right. What’s described as “the sort of film that could have been shot in eight weeks” would more likely have been a heroic flop, Clouzot’s colourful experimental material at odds with his earthy subject matter.

Generous extras include a talk by Clouzot expert Lucy Mazdon and They Saw Inferno, a documentary containing useful interviews with crew members. The introduction and extended interview with the infectiously upbeat Bromberg are both fun, especially when he explains exactly how he was able to gain access to the 185 cans of surviving footage.

rating

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Film

Can I get a Witness? review - time to die before you get old

Ann Marie Fleming directs Sandra Oh in dystopian fantasy that fails to ignite

Can I get a Witness? review - time to die before you get old

Ann Marie Fleming directs Sandra Oh in dystopian fantasy that fails to ignite

Happyend review - the kids are never alright

In this futuristic blackboard jungle everything is a bit too manicured

Happyend review - the kids are never alright

In this futuristic blackboard jungle everything is a bit too manicured

Robert Redford (1936-2025)

The star was more admired within the screen trade than by the critics

Robert Redford (1936-2025)

The star was more admired within the screen trade than by the critics

Blu-ray: The Sons of Great Bear

DEFA's first 'Red Western': a revisionist take on colonial expansion

Blu-ray: The Sons of Great Bear

DEFA's first 'Red Western': a revisionist take on colonial expansion

Spinal Tap II: The End Continues review - comedy rock band fails to revive past glories

Belated satirical sequel runs out of gas

Spinal Tap II: The End Continues review - comedy rock band fails to revive past glories

Belated satirical sequel runs out of gas

Downton Abbey: The Grand Finale review - an attemptedly elegiac final chapter haunted by its past

Noel Coward is a welcome visitor to the insular world of the hit series

Downton Abbey: The Grand Finale review - an attemptedly elegiac final chapter haunted by its past

Noel Coward is a welcome visitor to the insular world of the hit series

Islands review - sunshine noir serves an ace

Sam Riley is the holiday resort tennis pro in over his head

Islands review - sunshine noir serves an ace

Sam Riley is the holiday resort tennis pro in over his head

theartsdesk Q&A: actor Sam Riley on playing a washed-up loner in the thriller 'Islands'

The actor discusses his love of self-destructive characters and the problem with fame

theartsdesk Q&A: actor Sam Riley on playing a washed-up loner in the thriller 'Islands'

The actor discusses his love of self-destructive characters and the problem with fame

Honey Don’t! review - film noir in the bright sun

A Coen brother with a blood-simple gumshoe caper

Honey Don’t! review - film noir in the bright sun

A Coen brother with a blood-simple gumshoe caper

The Courageous review - Ophélia Kolb excels as a single mother on the edge

Jasmin Gordon's directorial debut features strong performances but leaves too much unexplained

The Courageous review - Ophélia Kolb excels as a single mother on the edge

Jasmin Gordon's directorial debut features strong performances but leaves too much unexplained

Blu-ray: The Graduate

Post #MeToo, can Mike Nichols' second feature still lay claim to Classic Film status?

Blu-ray: The Graduate

Post #MeToo, can Mike Nichols' second feature still lay claim to Classic Film status?

Add comment