theartsdesk Q&A: Filmmaker Hou Hsiao-hsien | reviews, news & interviews

theartsdesk Q&A: Filmmaker Hou Hsiao-hsien

theartsdesk Q&A: Filmmaker Hou Hsiao-hsien

Plain talk from the great Taiwanese auteur behind 'The Assassin'

The mesmerising martial arts drama The Assassin consolidates the reputation of the Taiwanese filmmaker Hou Hsiao-hsien as one of world cinema’s pre-eminent artists. Every film he has made since the emergence of his mature aesthetic – grounded in long shots, narrative economy, and the kind of emotional reticence that characterises Yasujiro Ozu’s work – has the quality of a revelatory, almost sacred text.

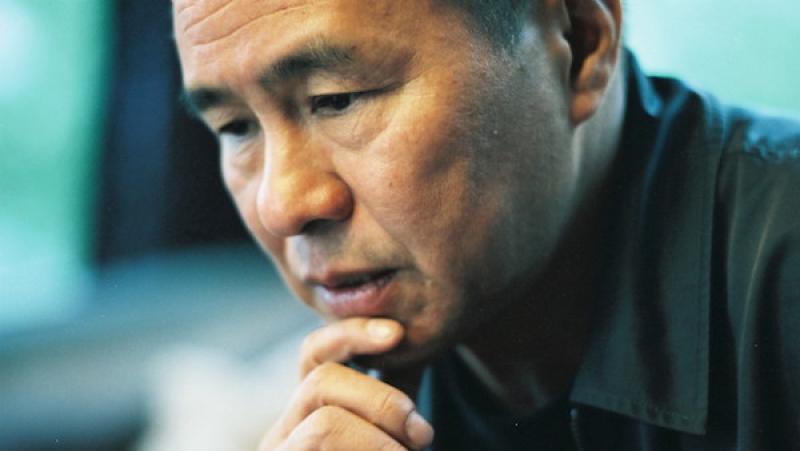

The 68-year-old director talked with theartsdesk in a Manhattan conference room last October, when The Assassin was screening at the New York Film Festival. He knows only a word or two of English, so a translator, occasionally helped by the three members of Hou’s Chinese party who sat with us, relayed his answers. They therefore have a slightly formal quality, though Hou spoke volubly in his authoritative undertone.

Graham Fuller: How did the film evolve as a complex, dynastic internecine story focused on an assassin reluctant to carry out certain killings?

Hou Hsiao-hsien: The original story’s not as complicated, actually. The film is based on a Tang Dynasty short story that’s about a girl who was taken away from her family and trained to be an assassin, but it continues on until she’s able to turn into a bug, and so it becomes fantastical. I didn’t want to tell the second half, but to concentrate on an origins-related story. I knew Shu Qi (pictured above) was the right actress to play the role, and that’s the main reason why I wanted to make it. Because of the amount of time I’ve spent working with her, I’m aware of the limitations of her performances, so, working within what I know of her and the story, I crafted what I thought she could do within the realm of the film. In terms of her not killing everyone she’s told to, maybe a story of a family exacting revenge for some reason is OK, but I don’t believe in people killing just to kill. From all these thoughts, the script slowly developed into what we’re now seeing on screen.

Hou Hsiao-hsien: The original story’s not as complicated, actually. The film is based on a Tang Dynasty short story that’s about a girl who was taken away from her family and trained to be an assassin, but it continues on until she’s able to turn into a bug, and so it becomes fantastical. I didn’t want to tell the second half, but to concentrate on an origins-related story. I knew Shu Qi (pictured above) was the right actress to play the role, and that’s the main reason why I wanted to make it. Because of the amount of time I’ve spent working with her, I’m aware of the limitations of her performances, so, working within what I know of her and the story, I crafted what I thought she could do within the realm of the film. In terms of her not killing everyone she’s told to, maybe a story of a family exacting revenge for some reason is OK, but I don’t believe in people killing just to kill. From all these thoughts, the script slowly developed into what we’re now seeing on screen.

Would the story have been very different if it had been set in the northern Five Dynasties period, say, or the southern Ten Kingdoms period [both 907-960], as opposed to during the Tang Dynasty [618-907]?

Yes, it would have been different visually. At the time it’s set in, there was a lot of political unrest between different kingdoms. If it had been set in a less turbulent era, everybody’s motives would have been different, requiring a different visual treatment. Because the story had been written during the Tang Dynasty, there was never any thought given to pushing it into a different era. And because it’s set in the middle of the Tang era, when all these small counties were wanting to gain independence by making military alignments, it was an interesting moment, like when America wanted to gain independence from Britain. Tang was a very different dynasty to the others for these reasons.

Is Yinniang’s lack of ruthlessness – her compassion – attributable to her being female, or not?

No, it’s not a gender thing. Men might not kill somebody for the same reason she doesn’t. And just as there are evil men, there are evil women, too. As in the original story, Yinniang succeeds in assassinating somebody the first time, but on the second round a child is there, and she can’t do it, which shows her humanity. But when she goes back to her master, she is reprimanded.

Is it known there were female assassins at the time of the Tang Dynasty?

Yes. It’s on record that there were women assassins during all the dynasties, and even after the 1911 Revolution [which established the Republic of China].

There’s no conscious correlation between those things and what’s going on with her internally. Even the flowing curtains that conceal her [in the governor Tian Ji’an’s rooms at the Weibo military garrison] are simply stirred by natural winds coming in. I just liked the way it looked. In terms of the mists in the mountains, that’s what was there, naturally, at an altitude of 2,700 feet. They would just build and dissipate. Again, I liked the way they looked.

Can you specify how you were influenced by [Akira] Kurosawa’s samurai movies?

As a kid, I watched a lot of samurai films, so naturally The Assassin would look like an homage to them. What I mainly took from Japanese cinema was the realism and the crafting of the art of fighting. It was so passionate that people are still learning it in Japan, whereas sword fighting in Chinese films these days has more of a dance quality. There’s no craft to it, so it has none of the power of fights in Japanese films. Yinniang uses a short sword, which dictated the type of fighting we would show. At the end of the day, it always translated into the power I see in samurai fighting motions. Realism was the main rule.

You frequently subordinate the story to evoking the atmosphere of places, while distancing yourself from incidents through your familiar use of long shots. And since there are gaps in the narrative, the characters’ identities, and their relationships to each other, aren’t always clear. Does it bother you that Western viewers in particular might not appreciate this distanced, elliptical way of telling a story?

When I’m on set, or working outdoors in a specific place, capturing the mood is the most important thing to me. I like using the long shot rather than shooting a scene from different angles or from closer in. Hollywood does the best kinds of movies like that because it has the resources for it, including the actors. In Asia, there are limitations on the kinds of actors I want to work with. Anyway, there are other ways to tell a story. Telling a story in a more straightforward way doesn’t feel right to me, and because of the rules I have for myself, I’m not sure that if I was given the opportunity to make such a film that I could even do it. If Western viewers maybe do not appreciate the way I feel I have to make a film, that’s their prerogative.

Do you see The Assassin as an historical film primarily, or is it more mythical?

Do you see The Assassin as an historical film primarily, or is it more mythical?

Neither. It’s just my view of humanity captured with my version of realism, and it doesn’t really matter which era it is. I was more focused on creating limitations for myself in terms of establishing Yinniang’s origins, as I mentioned, and once those limitations were set I felt totally free to create anything I wanted within that realm.

Your film A City of Sadness (pictured above) deals explicitly with the Chinese Kuomintang’s brutal oppression of the Taiwanese in 1947. I wondered if you intended the tense relationship between the Chinese Imperial Court and the Weibo garrison in The Assassin to mirror the current state of affairs between China and Taiwan?

I don’t think this is a political film and, if one steps back, I think you can see it doesn’t reflect the relationship between China and Taiwan. I wasn’t interested in using The Assassin as an allegory for anything – I just wanted to tell the story of this woman. Of course, when I did A City of Sadness, I was a lot younger and I had a lot of issues with the way the Kuomintang had come in and set Taiwan on the path to where it is today. If it hadn’t won the Golden Lion [at the Venice Film Festival], it never would have been released in Taiwan. Actually. the government requested some cuts, and it wasn’t until journalists made a big fuss about it that the film could be shown as it was. But that was many years ago and I no longer have the same… you know, if I wanted to make a political statement now, I would make a political film.

After spending nearly a decade making such an elaborate period film in places like Inner Mongolia and Kyoto, are you now inclined to do another modern urban film again, something like Millennium Mambo (pictured left, Shu Qi) or Café Lumière?

After spending nearly a decade making such an elaborate period film in places like Inner Mongolia and Kyoto, are you now inclined to do another modern urban film again, something like Millennium Mambo (pictured left, Shu Qi) or Café Lumière?

I feel my next film is actually going to be harder than The Assassin. When the Japanese occupied Taipei, the land they used was mostly farmland and they dug all these ditches as part of the irrigation system that supplied the water for agriculture. When they left, they didn’t fill up the ditches, but covered them, so a lot of water still flows underneath the city. The story will be about two young people who are researching this and, in some weird way, they may awaken a being – like a mythical creature – that exists within this world. I’m not quite sure how I’m going to shoot it yet, but it’s definitely the film I want to make next.

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Lady Gaga, The Mayhem Ball, O2 review - epic, eye-boggling and full of spirit

One of the year's most anticipated tours lives up to the hype

Lady Gaga, The Mayhem Ball, O2 review - epic, eye-boggling and full of spirit

One of the year's most anticipated tours lives up to the hype

Get Down Tonight, Charing Cross Theatre review - glitz and hits from the 70s

If you love the songs of KC and the Sunshine Band, Please Do Go!

Get Down Tonight, Charing Cross Theatre review - glitz and hits from the 70s

If you love the songs of KC and the Sunshine Band, Please Do Go!

Nick Helm, Touring review - brash comic shows his vulnerable side

Matters of the heart and heavy metal

Nick Helm, Touring review - brash comic shows his vulnerable side

Matters of the heart and heavy metal

Slovenian avant-folk outfit Širom’s 'In the Wind of Night, Hard-Fallen Incantations Whisper' opens the door to inner space

Unconventional folk-based music which sounds like nothing else

Slovenian avant-folk outfit Širom’s 'In the Wind of Night, Hard-Fallen Incantations Whisper' opens the door to inner space

Unconventional folk-based music which sounds like nothing else

One Battle After Another review - Paul Thomas Anderson satirises America's culture wars

Leonardo DiCaprio, Teyana Taylor, and Sean Penn star in a rollercoasting political thriller

One Battle After Another review - Paul Thomas Anderson satirises America's culture wars

Leonardo DiCaprio, Teyana Taylor, and Sean Penn star in a rollercoasting political thriller

Black Rabbit, Netflix review - grime and punishment in New York City

Jude Law and Jason Bateman tread the thin line between love and hate

Black Rabbit, Netflix review - grime and punishment in New York City

Jude Law and Jason Bateman tread the thin line between love and hate

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

First Person: Manchester Camerata's Head of Artistic Planning Clara Marshall Cawley on questioning the status quo

Five days of free events with all sorts of audiences around Manchester starts tomorrow

First Person: Manchester Camerata's Head of Artistic Planning Clara Marshall Cawley on questioning the status quo

Five days of free events with all sorts of audiences around Manchester starts tomorrow

The Hack, ITV review - plodding anatomy of twin UK scandals

Jack Thorne's skill can't disguise the bagginess of his double-headed material

The Hack, ITV review - plodding anatomy of twin UK scandals

Jack Thorne's skill can't disguise the bagginess of his double-headed material

Punch, Apollo Theatre review - powerful play about the strength of redemption

James Graham's play transfixes the audience at every stage

Punch, Apollo Theatre review - powerful play about the strength of redemption

James Graham's play transfixes the audience at every stage

Cinderella/La Cenerentola, English National Opera review - the truth behind the tinsel

Appealing performances cut through hyperactive stagecraft

Cinderella/La Cenerentola, English National Opera review - the truth behind the tinsel

Appealing performances cut through hyperactive stagecraft

Add comment