The Story of The Beatles' Last Song | reviews, news & interviews

The Story of The Beatles' Last Song

The Story of The Beatles' Last Song

Extract from a new Kindle single about the recording of 'Abbey Road'

Summer was nigh. In May 1969 the Lennons bought Tittenhurst Park, an 85-acre estate in the same stockbroker belt as John’s first Beatles home, Kenwood. It needed work and a while would pass before they moved in. At EMI, John and Yoko busied themselves with their resistible third LP, The Wedding Album. Heroin intake was vigorous.

There were many soi-disant Apple-Allen Klein business meetings through April and May, most of which went nowhere. One of them, however, at Olympic Studios in Barnes in south-west London (on 9 May), was overshadowed by three Beatles having, the previous day, pledged their signatures to management by ABKCO, and a fourth – Paul McCartney – now and forever withholding his, and confirming it. After the Klein-gang who wanted McCartney on board had marched off, Paul spent the rest of the evening at Olympic bashing drums and doing backing vocals for Steve Miller, who was there recording a song called “My Dark Hour”.

Beatles songs such as “Octopus’s Garden”, “Oh! Darling” and “Something” were taking shape. At Olympic, where producer Glyn Johns continued to chisel away at Twickenham’s “Get Back” sessions of January 1969, a medley beginning with a song about lack of cash-flow - brainchild of McCartney’s, this, oddly enough - began to germinate. At some point - no exact date in May (or June at the latest) has been nailed - McCartney rang George Martin and asked if the five could get back together. Could they make another LP just the way they used to? Martin agreed that was the only way they could do it.

Sometimes, miracles have happened for real.

There was no plan, contractually fixed and certain, or otherwise, for the next Beatles album. In the first quarter of 1969 it was probable there’d be no more Beatles music. The fluke of the single “The Ballad of John and Yoko”, recorded in April (and backed by Harrison’s rollicking “Old Brown Shoe”, a great and neglected B-side) was really down to there being no other Beatles around to record Lennon’s diary-rocker than McCartney; and who better than McCartney did Lennon have to do his bidding? The opposite of “band commitment”, however it might be characterised - absenteeism, ennui, anger - might have been emblematic of where The Beatles had arrived by the start of the year’s second quarter. But when it came to their going back into EMI, it was a matter of who-had-what and, Christ, let’s-see-what-we-can-make-of-it if we dare!

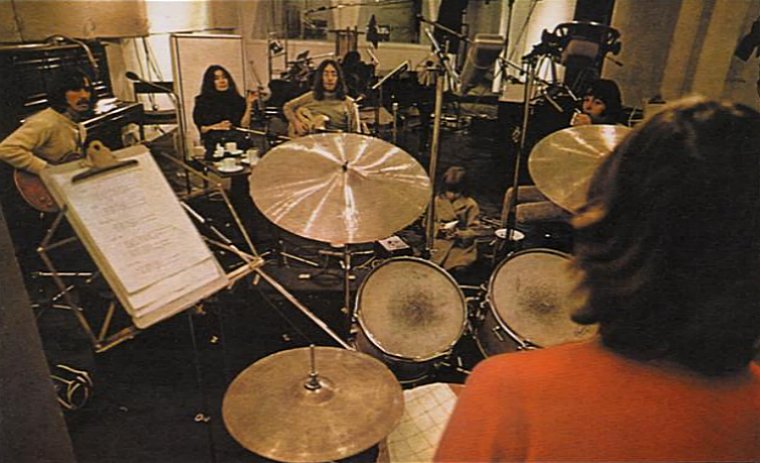

With any other outfit this would have led to more or less a mess, however forgiveable, languishing no doubt for sessions super-experts to pick through in the years ahead. This outfit was The Beatles. They’d had nothing to prove since 1965. Now, they preferred the company of their wives, families, girlfriends and other musicians; more or less anyone except each other. The staying power the four found as they sought to work together in EMI’s large house in St John’s Wood that last summer was, with a bit of help from George Martin, as epic as anything they’d pulled from the hat since Hamburg.

With any other outfit this would have led to more or less a mess, however forgiveable, languishing no doubt for sessions super-experts to pick through in the years ahead. This outfit was The Beatles. They’d had nothing to prove since 1965. Now, they preferred the company of their wives, families, girlfriends and other musicians; more or less anyone except each other. The staying power the four found as they sought to work together in EMI’s large house in St John’s Wood that last summer was, with a bit of help from George Martin, as epic as anything they’d pulled from the hat since Hamburg.

Yet it’s as well to realise that there was by 1969 little or no chronological method to how The Beatles were recording. Ideas would form and takes be taped, sometimes dozens of them, sometimes performed by only one or two Beatles present. Overdubs would follow that would be reduced to a master. Further instrumentation and vocals could and would be added to that. The Beatles were using each other to have a go with songs they each had, and unity was really no longer an issue. And tempting as it might be to think of Abbey Road’s track order as the one the band must surely have started out with – mainly because it seems, and for over four decades has seemed perfectly sequential – it didn’t happen that way at all.

“Maxwell’s Silver Hammer” (3), “Oh! Darling” (4) and “Octopus’s Garden” (5) had basic life before and/or during Twickenham. “I Want You” (6) came immediately after, at Apple, as did “She Came in Through the Bathroom Window” (13). “Something” (2) was first taped the day after the “I Want You” edit of its three favoured takes of 23 February. Then, with over a month’s gap, came first signs of a medley, just alluded to, with McCartney’s “You Never Give Me Your Money” (9), on 6 May.

Much of the content of this caressing, gladdening track was provided by Ono

Nearly two more months passed, with holidays and time off from the studio at least (if not from Klein matters), before the meat of the album was tackled. Lennon and Ono, John’s son Julian and Yoko’s daughter Kyoko with them, had a car accident while trying to holiday in Scotland at the start of July; hospitalised, the two of them didn’t appear at EMI until the 9th. Record tells us that the first week of work back at Abbey Road without them was uncommonly light and breezy.

Every weekday from 1 July to 29 August, 2.30-10.00 pm, the Abbey Road studios were booked for The Beatles. First track to be finished was “Her Majesty” (17), recorded by McCartney on 2 July. That same session also saw “Golden Slumbers” (14) and “Carry That Weight” (15) come to life. Harrison’s “Here Comes the Sun” (7) emerged - without Lennon - on the 7th. When Lennon did arrive (Ono, now pregnant and still suffering injuries from the crash, was enthroned in a double bed and provided with a microphone into which she should, and did, simper her wisdom about what was being played in the studios), “Maxwell…” was in progress and remained so until the 15th.

On the 21st Lennon eagerly unleashed “Come Together”. Because it is first on the album it has become almost Abbey Road’s signature tune. It was another free-associating riddle, Lennon’s voice more expectorating and ethereal than it had ever been, the title lifted from a recent Timothy Leary political campaign in California. Ono is in there too, adjectivally a “sideboard” and as the other half of “Bag Productions”, a company the Lennons had formed in April for their art marvels, with Apple naturally at its service. A couple of days later The Beatles were still working on “Come Together” and taping what would become “The End” (16). Within a few days of that came the unmistakably Lennon side-two sequence from “Sun King” to “Polythene Pam” (10-12) and, right at the beginning of August, his “Because” (8).

Much of the content of this caressing, gladdening track was provided by Ono. Lennon had been listening to her play on the piano the opening of Beethoven’s “Moonlight Sonata”. What lodged in his mind was a sequence of D-minor notes that mirrored exactly the arpeggio in “I Want You”. On “Because” the Beethoven notes were reversed. When the track emerged, George Martin played the intro on an electric Baldwin spinet harpsichord; these arpeggios were then picked up by Lennon’s electric guitar, and three Beatles - John, Paul and George - chimed in together in close, three-part harmony, in one of their tightest ever bits of vocalese.

Much of the content of this caressing, gladdening track was provided by Ono. Lennon had been listening to her play on the piano the opening of Beethoven’s “Moonlight Sonata”. What lodged in his mind was a sequence of D-minor notes that mirrored exactly the arpeggio in “I Want You”. On “Because” the Beethoven notes were reversed. When the track emerged, George Martin played the intro on an electric Baldwin spinet harpsichord; these arpeggios were then picked up by Lennon’s electric guitar, and three Beatles - John, Paul and George - chimed in together in close, three-part harmony, in one of their tightest ever bits of vocalese.

The song still had two sessions more before it was done: voices, and overdubs by Moog synthesiser, heard at just over a minute-and-a-half in, played by Harrison on a machine he’d acquired in Hollywood the previous November. The wondrousness of the music a given, the dreamy words reflecting benign infinity were also very much Ono’s imprimatur. In a peculiar way that exceeds most normal human relationships, husband was now practically being “written” by wife.

Rather a brilliant move, which wouldn’t take place until 20 August when Abbey Road’s song order was finalised, was to separate “Because” from “I Want You” by only one track, “Here Comes the Sun”. In the old days of the LP, the act of flipping the record would have delayed in the unconscious the exact relationship between sides one and two, but delay made recognition all the more exciting. Though it seemed that a strange and abrupt finality had been reached by the end of track six, where it cuts out, a simple arpeggio gave linkage and continuity. This effect can be heard much more quickly today, which perhaps makes it sound contrived where it once wasn’t; either way, musicologically Abbey Road was and is more of a piece than not, even outside the side-two medley.

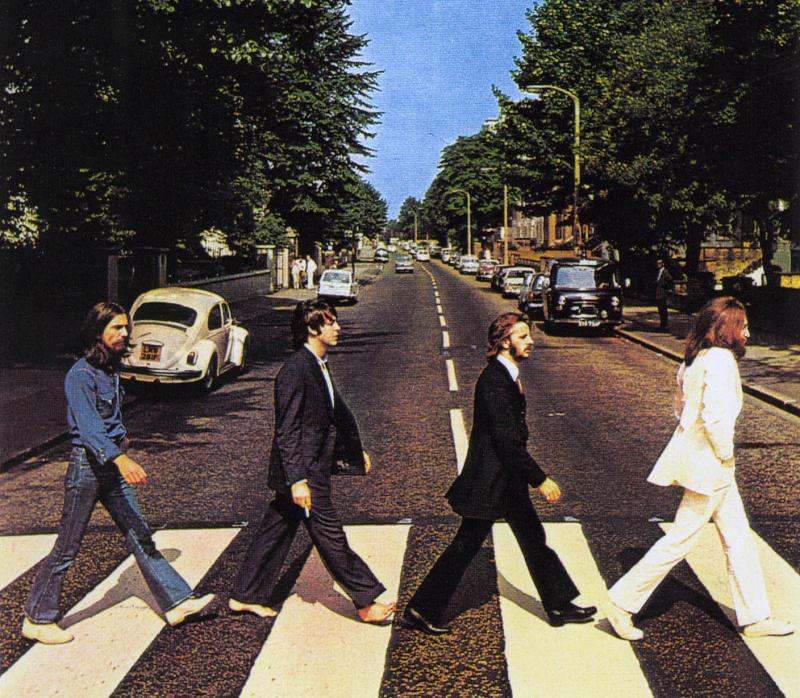

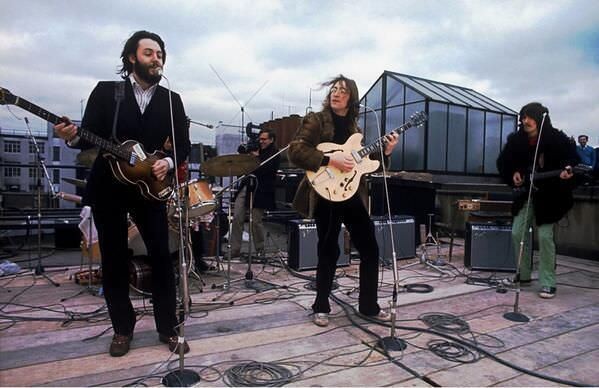

They were nearly there. On the seventh day of August, John, Paul and George abandoned themselves to the frenetic guitar solos of the end of “The End” (“like they had gone back in time, like they were kids again, playing together for the sheer enjoyment of it”, wrote engineer Geoff Emerick in 2006), which follow Ringo’s only Beatles drum solo. The next day, bright and sunny, they were in earlier than usual to be photographed. Iain Macmillan shot, from a ladder, a few on his film of the four walking over a zebra crossing outside Abbey Road Studios. One image - just one - was needed for the album’s front cover.

The day after that Lennon took to the Moog and, with Starr on an Abbey Road white-noise machine, proceeded to overdub the whirring and whooshing on to the remaining three minutes of the 18 April reduction of “I Want You”. The song was building into a thing of geological immensity but still didn’t know where to stop. Perhaps because of its weight, the following Monday, when more voice work was done, the “(She’s So Heavy)” parenthesis was appended to “I Want You”.

The Lennons moved into Tittenhurst Park in the second half of August. Further engineering, editing and mixing were done to Abbey Road; George Martin brought in orchestration. On the 20th, The Beatles spent a long evening and night in studios three and two deciding how “I Want You” should end and Abbey Road be ordered. For the latter, the two sides were reversed. For a time it was possible the record would end with Lennon’s huge track but, rightly, to finish with “The End” (“Her Majesty” aside) made the only sense.

On “I Want You”, Emerick was instructed by Lennon to snip the tape of the track, with no rhyme or reason - just where he (Lennon) deemed it should happen (at seven minutes 44 seconds, as it turned out). So that’s what Emerick did. That’s where it stopped. The randomness of it was in keeping with Lennon’s Ono-inspired aesthetic of anything-can-happen, one of the driving forces behind The White Album. The Beatles were at least being artistically more consistent than might have been apparent on that date.

After it, the four would never meet at Abbey Road again.

- The Story of The Beatles' Last Song is available as a Kindle single on Amazon for £1.99

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more New music

Pop Will Eat Itself's 'Delete Everything' is noisy but patchy

Despite unlovely production, the Eighties/Nineties unit retain rowdy ebullience

Pop Will Eat Itself's 'Delete Everything' is noisy but patchy

Despite unlovely production, the Eighties/Nineties unit retain rowdy ebullience

Music Reissues Weekly: The Earlies - These Were The Earlies

Lancashire and Texas unite to fashion a 2004 landmark of modern psychedelia

Music Reissues Weekly: The Earlies - These Were The Earlies

Lancashire and Texas unite to fashion a 2004 landmark of modern psychedelia

Odd times and clunking lines in 'The Life of a Showgirl' for Taylor Swift

A record this weird should be more interesting, surely

Odd times and clunking lines in 'The Life of a Showgirl' for Taylor Swift

A record this weird should be more interesting, surely

Waylon Jennings' 'Songbird' raises this country great from the grave

The first of a trove of posthumous recordings from the 1970s and early 1980s

Waylon Jennings' 'Songbird' raises this country great from the grave

The first of a trove of posthumous recordings from the 1970s and early 1980s

Lady Gaga, The Mayhem Ball, O2 review - epic, eye-boggling and full of spirit

One of the year's most anticipated tours lives up to the hype

Lady Gaga, The Mayhem Ball, O2 review - epic, eye-boggling and full of spirit

One of the year's most anticipated tours lives up to the hype

Slovenian avant-folk outfit Širom’s 'In the Wind of Night, Hard-Fallen Incantations Whisper' opens the door to inner space

Unconventional folk-based music which sounds like nothing else

Slovenian avant-folk outfit Širom’s 'In the Wind of Night, Hard-Fallen Incantations Whisper' opens the door to inner space

Unconventional folk-based music which sounds like nothing else

'The Art of Loving': Olivia Dean's vulnerable and intimate second album

Neo soul Londoner's new release outgrows her debut

'The Art of Loving': Olivia Dean's vulnerable and intimate second album

Neo soul Londoner's new release outgrows her debut

Music Reissues Weekly: The Peanut Butter Conspiracy - The Most Up Till Now

Definitive box-set celebration of the Sixties California hippie-pop band

Music Reissues Weekly: The Peanut Butter Conspiracy - The Most Up Till Now

Definitive box-set celebration of the Sixties California hippie-pop band

Doja Cat's 'Vie' starts well but soon tails off

While it contains a few goodies, much of the US star's latest album lacks oomph

Doja Cat's 'Vie' starts well but soon tails off

While it contains a few goodies, much of the US star's latest album lacks oomph

Mariah Carey is still 'Here for It All' after an eight-year break

Schmaltz aplenty but also stunning musicianship from the enduring diva

Mariah Carey is still 'Here for It All' after an eight-year break

Schmaltz aplenty but also stunning musicianship from the enduring diva

Album: Solar Eyes - Live Freaky! Die Freaky!

Psychedelic indie dance music with a twinkle in its eye

Album: Solar Eyes - Live Freaky! Die Freaky!

Psychedelic indie dance music with a twinkle in its eye

Add comment