Dennis Hopper: The Lost Album, Royal Academy | reviews, news & interviews

Dennis Hopper: The Lost Album, Royal Academy

Dennis Hopper: The Lost Album, Royal Academy

Actor's black and white images are a bustling Sixties time capsule

From Apocalypse Now to Blue Velvet to Speed, as a screen presence Dennis Hopper grew ever more scary. Lately gallery-goers have got to know another side of Hopper via his painting. Now there is a belated run-out for his work as a photographer, although work is maybe the wrong word. He spent much of the Sixties with a camera slung round his neck, but didn’t make a dime from any of his pictures.

The photographs on show at the Royal Academy have a strong flavour of the time capsule. There are 400 of them shot between 1961 and 1967, almost all of them prints unearthed after his death in 2010, and they fall across two main categories. A busload of famous faces crops up in his viewfinder, mainly actors encountered on set and artists he met in the burgeoning art scene of LA. A tour of Hopper’s world is like entering an elegant if breathless gossip column through whose pages the likes of Hockney and Lichtenstein, Warhol and the dashing Ruscha wander. He also seems to have popped up at all the important moments in Sixties iconography. That’s Hopper tagging along on the Selma-Montgomery civil rights march, snapping riots in LA or hanging with Timothy Leary’s flower children or Hell’s Angels encrusted in leather (see gallery overleaf). All the way through he’s hunting for the humanity, which explains his particular affinity for children who have not yet learned to pose.

Hopper may have shot as he found, but he evidently did a lot of looking first. Across all the images the predominant obsession is with light. Hence his abjuring of colour. A mesh of shadows falls across Paul Newman’s face (pictured right), and you just have to imagine the famous blue of those irises. A series of still lifes observe the play of light on wood grains in close-up, or monumental masonry in a Mexican graveyard. A shot of the surface of the moon as seen on TV is the ultimate destination in his pursuit of texture. The sun is a supporting player throughout, constantly on his shoulder. There are very few umbrellas in Hopper’s line of vision, even when he snaps the orators of Speaker’s Corner. Indeed an image titled Hopper House (Porch with Chiaroscuro) is a rarity, offering only flat light. Perhaps the title is a joke at the photographer’s expense.

Hopper may have shot as he found, but he evidently did a lot of looking first. Across all the images the predominant obsession is with light. Hence his abjuring of colour. A mesh of shadows falls across Paul Newman’s face (pictured right), and you just have to imagine the famous blue of those irises. A series of still lifes observe the play of light on wood grains in close-up, or monumental masonry in a Mexican graveyard. A shot of the surface of the moon as seen on TV is the ultimate destination in his pursuit of texture. The sun is a supporting player throughout, constantly on his shoulder. There are very few umbrellas in Hopper’s line of vision, even when he snaps the orators of Speaker’s Corner. Indeed an image titled Hopper House (Porch with Chiaroscuro) is a rarity, offering only flat light. Perhaps the title is a joke at the photographer’s expense.

He called himself a Duchampian finger-pointer (one of the figures at whom he pointed his finger was Duchamp himself). But while this feels like a pop-up portrait of a decade, Hopper’s own personal weirdness would thrust itself into the lens. He was creepily keen on shooting dolls and mannequins, a somehow unnatural extension of his all-American passion for airbrushed lovelies on billboards. He also had a wit’s eye for the unusual – a yard full of identical clown figures, a man standing on a set of scales in the street.

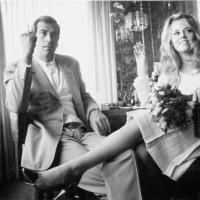

The narrative of the show’s hang suggests he outgrew a young man’s interest in persuading women to take their clothes off. For a decade in which sexual intercourse is said to have been invented, there is very little of that going on. The most erotic image finds Jane Fonda’s leg draped across the lap of her new husband Roger Vadim. The flower children look as if sex is the last thing on their innocent minds.

Overleaf: view a gallery of images from the exhibition

Click on the thumbnails to enlarge

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Add comment