Bridget Riley: The Stripe Paintings, David Zwirner | reviews, news & interviews

Bridget Riley: The Stripe Paintings, David Zwirner

Bridget Riley: The Stripe Paintings, David Zwirner

The more one looks the more one can admire rather than love the artist's passionate exactitude

Bridget Riley’s mural for St Mary’s Hospital in Paddington, which was unveiled in April this year, is something I’ve seen only in photographs. And on seeing it for the first time my reaction, I’m afraid, was, “Oh no". It obviously didn’t help that the photographer had wildly exaggerated the one-point perspective, so that the parallel lines of two facing walls converging sharply made you feel the vertiginous pull of a rabbit hole.

But that was a photograph. Riley’s paintings don’t reproduce at all well, though it’s usually the case that in reproduction they lose, rather than gain, their nausea-inducing potential. The optical effects employed in her canvases which make it very difficult for the eye to focus are another matter. You get a hint of their effects in reproduction, but it’s nothing like the experience of standing in front of an actual painting. Today she’s much more interested in colour as a way to flood the senses rather than disorientate them.

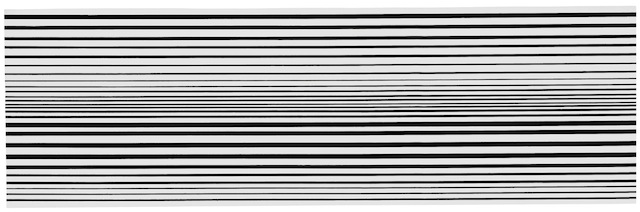

Riley has used an array of geometrical forms in her pursuit of vibrating movement. But the stripes – horizontal, vertical, diagonal – have been consistent throughout her long career (she’s a surprisingly youthful and energetic 83). This exhibition consists of 15 stripe paintings, as well as studies on paper, beginning, though it’s by no means a chronological hang, with the 1961 Horizontal Vibration (pictured below). This was painted in the year Riley abandoned figuration altogether, producing a number of black and white Op-art paintings, including the better-known Movement in Squares, whose black and white checks are painted as if the canvas is curving and dipping at the vertical point of the golden section.

In Horizontal Vibration a similar concertinaed effect is achieved by painting black bands in various densities and differing proximities to one another, creating a dense blur that runs horizontally through the centre of the canvas. The effect is literally dazzling, the lines undulating like a hypnotic sea current. One often thinks of things in nature for Riley’s abstractions, and she herself frequently titles her work with an eye on the natural world, though I admit I also can't help thinking of sweets – Humbugs, liquorice candies, a stick of that Blackpool Rock. Either way, your gaze searches for a resting point but there’s no purchase.

In Horizontal Vibration a similar concertinaed effect is achieved by painting black bands in various densities and differing proximities to one another, creating a dense blur that runs horizontally through the centre of the canvas. The effect is literally dazzling, the lines undulating like a hypnotic sea current. One often thinks of things in nature for Riley’s abstractions, and she herself frequently titles her work with an eye on the natural world, though I admit I also can't help thinking of sweets – Humbugs, liquorice candies, a stick of that Blackpool Rock. Either way, your gaze searches for a resting point but there’s no purchase.

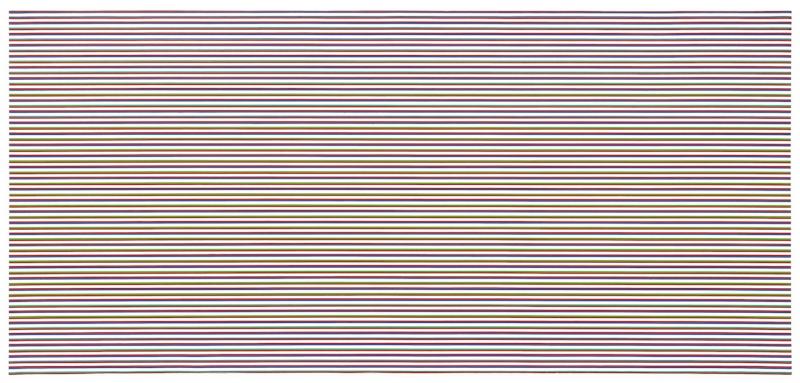

By 1967, Riley had moved into colour, beginning her soft transition via a series of paintings using subtle colours – gradations of grey. By the time she comes to paint her huge 1969 canvas Late Morning (Horizontal) (main picture) bright complementary colours, these separated by bars of blazing white in rhythmic formation, have fully superseded the smoky monochrome effect.

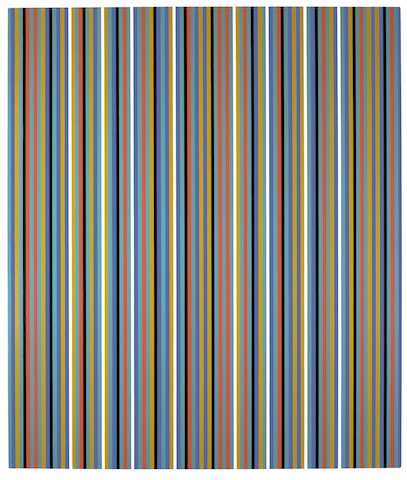

One thinks naturally of Dan Flavin’s fluorescent tubes when confronted by the diagonals (purple, green, orange, white) of the diptych Prairie, 2003/1973. And one thinks too of James Turrell, the Californian light artist, for what Riley achieves with paint others have only achieved with the immersive optical effects of coloured light. Her works seen in series feels less a display of individual paintings than an immersive installation which affects a build-up of physical responses. (Pictured right: Après Midi, 1981)

One thinks naturally of Dan Flavin’s fluorescent tubes when confronted by the diagonals (purple, green, orange, white) of the diptych Prairie, 2003/1973. And one thinks too of James Turrell, the Californian light artist, for what Riley achieves with paint others have only achieved with the immersive optical effects of coloured light. Her works seen in series feels less a display of individual paintings than an immersive installation which affects a build-up of physical responses. (Pictured right: Après Midi, 1981)

I’m not sure if I can ever be moved by Riley, but she’s an artist one can certainly deeply admire, in that way that Seurat, with his scientific investigations in to colour and his deep knowledge of the way spots and dashes of unmixed pigments interact by a process of optical mixing at an optimum distance, is deeply admired but just a little less loved. Though her colours shimmer and burn on the retina, she doesn’t produce the joy of a Matisse nor a kind of sublime transcendence of a color field painter like Rothko. But the more one looks the more one admires her passionate exactitude.

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Yoshitomo Nara, Hayward Gallery review - sickeningly cute kids

How to make millions out of kitsch

Yoshitomo Nara, Hayward Gallery review - sickeningly cute kids

How to make millions out of kitsch

Hamad Butt: Apprehensions, Whitechapel Gallery review - cool, calm and potentially lethal

The YBA who didn’t have time to become a household name

Hamad Butt: Apprehensions, Whitechapel Gallery review - cool, calm and potentially lethal

The YBA who didn’t have time to become a household name

Add comment