Listed: The Vikings - Life and Legend | reviews, news & interviews

Listed: The Vikings - Life and Legend

Listed: The Vikings - Life and Legend

The curator of the British Museum's landmark show picks 10 exhibits that tell the Viking story

The British Museum's exhibition The Vikings: Life and Legend promises to redefine the Viking age for a new generation. First seen at the National Mueum in Copenhagen, it has now travelled - much as the show's subjects once did - across the North Sea. It includes objects from 25 lending institutions spread across nine countries - 10 if you include Scotland, whose national law requires export licence.

1 Which exhibit says something new and unexpected about the Vikings?

A sorceress’s grave from Fyrkat in Denmark. One find in the grave is a pot which we know contained make-up. Most tend to have a view of the Vikings as not particularly well-kempt. We know from other evidence that they took a lot of care of their hair – combs are common. But make-up is unusual. We don’t know how this strong white make-up was applied. It was possibly for patterns and designs on the face and possibly a completely whited-out face. The other possibility is that, because of the role sorceresses seem to have had in society, it could be that one half was completely white and the other normal, representing Hel who was the goddess responsible for the afterlife of those not deemed worthy for Valhalla. That name seems to be where we get our name for Christian Hell from. An account from an Arab traveller who visited Denmark in the second half of the 10th century around the time Fyrkat was being built records the fact that Viking men and women wore makeup round the eyes to make their eyes bright.

2 ...underpins their reputation for bloodthirstiness?

A jawbone of a skull with filed front teeth. The idea of Vikings as raiders and warriors defines the Viking age, but it’s a small minority who give the whole society a reputation for atrocities, unpleasantness and antisocial behaviour. Viking meant pirate or marauder. In this jawbone the front teeth have been filed across. A number are found in warrior burials in Scandinavia. This comes from a mass grave in England. The view seems to be these fill marks were probably coloured in as well. It would have a very striking effect. If you either bared your teeth or grinned at someone in battle it’s distracting and also there’s that sense of "if you’re willing to do that to yourself, what are you willing to do to me?"

3 ...illustrates the exquisite craftsmanship?

3 ...illustrates the exquisite craftsmanship?

Hiddensee Hoard. One of the most splendid things in the exhibition includes a gold twisted neck ring, a large gold circular broach and a series of large gold pendants which would have been strung together in a necklace. Altogether the weight is 650g of solid gold. It’s decorated with really intricate gold filigree with stunning minute detail of animal heads. It was probably made in Denmark in the late 10th century but was found in Rügen, Germany. (Pictured above, Hoard of 14 filigree pendants, spacers, brooch and neck-ring © Jutta Grudziecki, Kulturhistorisches Museum der Hansestadt Stralsund)

4 ... highlights the cultural diversity existing under the umbrella term Viking?

A pendant found in Norway. Within Scandinavia we have a lot of peoples who would be related to the Finns and the modern Saami because they are nomadic peoples but we don’t have sites and therefore the finds that we have for the Nordic stereotype of the Vikings. But they crop up in the historical record. Though found in Norwary, the style is normally associated with the eastern Baltic - Finland and Estonia. It seems to be religious amulet. It has a pattern of interlace at the top and duck’s or swan’s feet dangling off the bottom. The argument is that this relates to what might be labelled today shamanism: animal spirits and shape-changing. The swan is significant within Finnish mythology. This is a reminder of the diversity of the Viking belief.

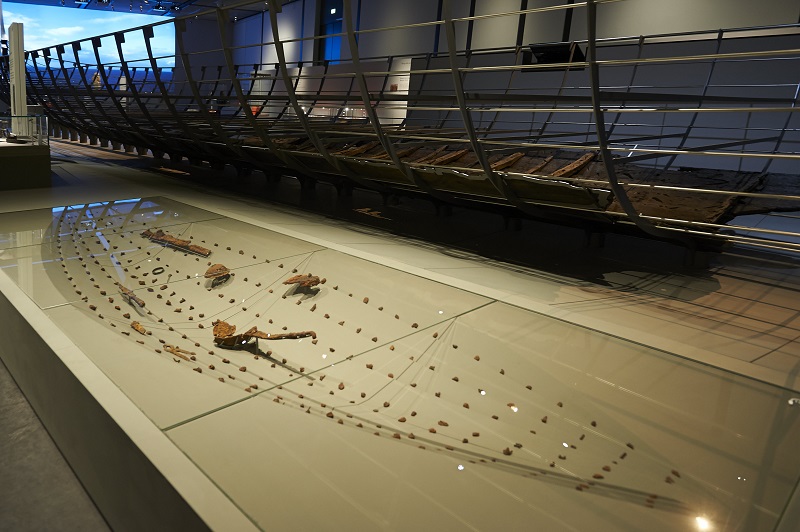

5... showcases the work of restoration presumably undertaken before the exhibition?

Roskilde 6. This is the largest ship ever found and probably one of the largest ever built. The process of restoring that was absolutely massive and indeed the full conservation only took place because the exhibition happening. It was found in 1997 along with eight others underneath the Viking ship museum in Roskilde. On the back of the exhibition, the Danish National Museum was able to get funding to carry out an extensive programme of conversation. That meant soaking all the timbers for several months, working out what shape they should have been, bending them back into the right shape, clamping them, soaking them in a chemical solution which replaced the water within the timber so that they would hold their shape without shrinkage. But it needed to a reversible process in the event that future conservations methods proved to be more suitable in the long term. Every timber had to be freeze-dried for six months, including timbers up to eight metres in length. Then a metal frame in the mean time had to be built that supports all the surviving timbers for display which at the same time suggests the shape of everything that’s missing. The whole thing has to be dismantlable so the whole thing can come in one container and flatpacked in true IKEA style. Altogether it was somewhere over three years. (Pictured above: installation of Roskilde 6 at the British Museum in the Sainsbury Exhibitions Gallery, January 2014 © Paul Raftery)

6 ... says something about the sheer magnitude of curatorial organisation involved?

Horde from Gnezdovo. This in itself is not that complicated a group of objects – a horse of silver containing Slavic and Viking material which shows the mix of cultures within Viking-age Russia. It comes from the State Historical Museum in Moscow. But it’s a reminder of how far we’ve had to go to find all the objects. Altogether we’ve got 25 lending institutions from different countries including Scotland, whose laws require an export licence. It’s been a logistical nightmare getting everything together. We could have had fantastic material from many other lenders but every lender adds to the cost.

7... underpins the idea that the Vikings are still with us?

Coin in the name of the last Viking king in the kingdom of Northumbria, Eric Bloodaxe. A lot of the evidence isn’t object-based - place names, personal names, dialect and even DNA. But we have the coin with the name of the last Viking king of Northumbria. Eric Bloodaxe is just such a great name. He’s one of the few Vikings that people have heard of by name because the Jorkik Centre, the Viking museum in York, for years had a whole load of merchandising around him. He did issue coins, minted in York between 952 and 954, and despite his name he was a dreadful king, a henpecked husband and very indecisive: great on the battlefield; but lost outside it. (Pictured above right: Penny of Eric Bloodaxe of Northumbria (c.952-4). England. © The Trustees of the British Museum)

Coin in the name of the last Viking king in the kingdom of Northumbria, Eric Bloodaxe. A lot of the evidence isn’t object-based - place names, personal names, dialect and even DNA. But we have the coin with the name of the last Viking king of Northumbria. Eric Bloodaxe is just such a great name. He’s one of the few Vikings that people have heard of by name because the Jorkik Centre, the Viking museum in York, for years had a whole load of merchandising around him. He did issue coins, minted in York between 952 and 954, and despite his name he was a dreadful king, a henpecked husband and very indecisive: great on the battlefield; but lost outside it. (Pictured above right: Penny of Eric Bloodaxe of Northumbria (c.952-4). England. © The Trustees of the British Museum)

8 ...points to the Viking presence in the British Isles?

Boat burial from Ardnamurchan. There is a lot of material from Viking Britain. One of the images we have of Vikings’ grand funerals, burials or burnings within boats. This is the first one to turn up within the British mainland, as recently as 2012. It doesn’t yet belong to any one museum and hasn’t yet been fully conserved. We have to get permission from the Scottish administrators to get a temporary export to display it in London. It’s lovely to have it beside the main ship. Roskidle 6’s timbers are preserved but all the iron rivets have rusted away. In a different type of soilm the timber has rotted way but the iron has been preserved. (Pictured below: Ardnamurchan boat burial, late 9th/early 10th century AD. Iron rivets and grave finds. © The Trustees of the British Museum.)

9 ...tells about the Viking attitude to money and/or women and/or the afterlife?

Keys from female graves from Denmark. Although in some ways Vikings has a sexist society, they weren’t shy about giving control to women. They had a lot more freedom than most contemporary Christian women. They could sue for divorce and own property in their own rights. juWhat’s important about these is burial goods are common prior to Christianisation. They symbolise the role of the deceased during life. One of the things that are very common in female grave is the keys because the woman held the keys to the strong room of the household. The men might be going out raiding or trading. Once they’d found the money, the woman had charge of household finances, making sure it isn’t just feasted away. Household finance was central to keeping going over the long winters.

10 ...predicts the end of the Viking age?

Manuscript featuring King Cnut. A manuscript that we borrowed from the British Library shows that Cnut the Great became king of England, went on very shortly afterwards to become king of Denmark and later conquered Norway and ruled part of Sweden. He was far and away the most powerful rule of the Viking age, creating this powerful empire. This manuscript has a picture of him. Although he’s Viking in origin it shows him very much as an Anglo-Saxon king with his wife presenting a cross to the new minster at Winchester. The manuscript is a book of people to be prayed for by religious houses. Although he’s Danish by background, what we see is a Christian European mainstream king at the end of the Viking age, when the Vikings stopped being distinctly Viking.

- Vikings: Life and Legend at the British Museum from 6 March to 22 June

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Photo Oxford 2025 review - photography all over the town

At last, a UK festival that takes photography seriously

Photo Oxford 2025 review - photography all over the town

At last, a UK festival that takes photography seriously

![SEX MONEY RACE RELIGION [2016] by Gilbert and George. Installation shot of Gilbert & George 21ST CENTURY PICTURES Hayward Gallery](https://theartsdesk.com/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail/public/mastimages/Gilbert%20%26%20George_%2021ST%20CENTURY%20PICTURES.%20SEX%20MONEY%20RACE%20RELIGION%20%5B2016%5D.%20Photo_%20Mark%20Blower.%20Courtesy%20of%20the%20Gilbert%20%26%20George%20and%20the%20Hayward%20Gallery._0.jpg?itok=7tVsLyR-) Gilbert & George, 21st Century Pictures, Hayward Gallery review - brash, bright and not so beautiful

The couple's coloured photomontages shout louder than ever, causing sensory overload

Gilbert & George, 21st Century Pictures, Hayward Gallery review - brash, bright and not so beautiful

The couple's coloured photomontages shout louder than ever, causing sensory overload

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Comments

We were there, It was

We were there, It was wonderfull!