My Hero: Ben Miller on Tony Hancock, BBC One | reviews, news & interviews

My Hero: Ben Miller on Tony Hancock, BBC One

My Hero: Ben Miller on Tony Hancock, BBC One

Homage to a genius of yesteryear works despite flimsy telly tropes

Tony Hancock stopped producing the work on which his reputation rests the best part of half a century ago. He still casts a long old shadow. Many years before BBC Four embarked on its series of biodramas, a life of Hancock starring Alfred Molina captured some of that hulking self-disgust. More recently Paul Merton has become a one-man module in Hancock studies, even going so far as to re-enact some of the old Half Hours.

There is always the danger, when contemporary comics make reverential films about their heroes, of falling at just such a hurdle. For some of Ben Miller’s homage to Hancock, you rather wished the BBC had simply rummaged in the archive and stuck on The Blood Donor and The Radio Ham. Those bits mostly found Miller trying to put Hancock’s genius into words, often when driving a retro-motor to shabby bits of the provinces where his life had played out. “Ben’s setting out on a journey to find out more about his comic idol,” advised the voiceover. A little bit of you dies whenever television vouchsafes such a prospect. (The many clips, incidentally, offered a window into a more confident past when learning in an audience was assumed. No modern BBC One controller would allow knowing jokes about Bertrand Russell to dodge the blue pencil.)

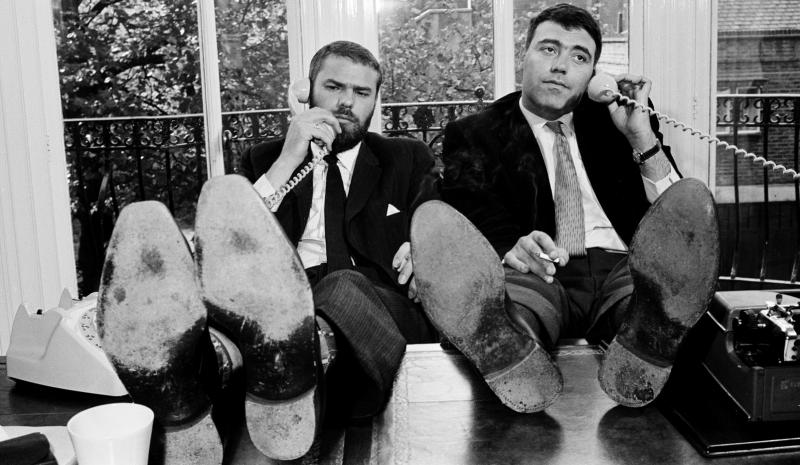

And yet if anyone hacks around in Hancock’s CV, they come across fun people to talk to. Not so much the dancing girls, now rather elderly, who remembered him as the comic turn on between the high-kicking limbs at the Windmill Theatre, nor the bloke who now lives in his old house and recycled stories of Hancock literally crawling home from the boozer. But Ray Galton and Alan Simpson (reachable by boat, for some risible non-reason) recounted their stories of working with a troubled talent as if for the first time. Their ear for his voice created a marriage that survived for 150 episodes. “Failure is much more interesting than success,” explained Simpson of Hancock’s harassed persona. (Pictured above right, Simpson, Hancock and Galton)

And yet if anyone hacks around in Hancock’s CV, they come across fun people to talk to. Not so much the dancing girls, now rather elderly, who remembered him as the comic turn on between the high-kicking limbs at the Windmill Theatre, nor the bloke who now lives in his old house and recycled stories of Hancock literally crawling home from the boozer. But Ray Galton and Alan Simpson (reachable by boat, for some risible non-reason) recounted their stories of working with a troubled talent as if for the first time. Their ear for his voice created a marriage that survived for 150 episodes. “Failure is much more interesting than success,” explained Simpson of Hancock’s harassed persona. (Pictured above right, Simpson, Hancock and Galton)

The partnership began to fray only after a car accident meant the star didn’t have enough time to learn their lines. Idiot boards off camera were intended as a temporary measure, but Hancock became almost as dependent on them as on alcohol – you could see both addictions doing their worst in his disastrous show at Royal Festival Hall a few years later. The prompt cards had the ruinous effect of immobilising his wonderfully rubbery face, like virtual Botox. (For a more detailed account of why Hancock split with the writers who served him so well, read Ray Galton overleaf).

The result of their split with Hancock was a forgotten film called The Punch and Judy Man. Sylvia Sims, playing Hancock’s wife in a dead marriage, explained that it was “about a man trying to tell you about the awfulness of comedy”. Hancock, like many a gifted comic who despises his talent, wanted to be a dramatic actor and quizzed Sims about “working with Johnny Mills and Anthony Quayle”. A far cry from taking feeds from Sid James and Richard Wattis.

The result of their split with Hancock was a forgotten film called The Punch and Judy Man. Sylvia Sims, playing Hancock’s wife in a dead marriage, explained that it was “about a man trying to tell you about the awfulness of comedy”. Hancock, like many a gifted comic who despises his talent, wanted to be a dramatic actor and quizzed Sims about “working with Johnny Mills and Anthony Quayle”. A far cry from taking feeds from Sid James and Richard Wattis.

A tragedy wrapped in a comedian: the old story. There was little investigation into the cause of Hancock’s relationship with the bottle, whose contents withered those hangdog features way beyond 44 years, his age when he died in a Sydney bedroom in 1968. But perhaps there was no need.

Overleaf: Ray Galton on the split with Tony Hancock

Ray Galton, who with Alan Simpson wrote Hancock's Half Hour and Hancock, recalls the reason for the split

Ray Galton, who with Alan Simpson wrote Hancock's Half Hour and Hancock, recalls the reason for the split

We split over Hancock’s second film. He obviously wanted to be successful internationally and that really meant in America. He had the idea about a Punch and Judy man performing on the south coast in winter time. We said, “That’s not really an international subject, is it?” We played around with it for a while, we had a week down in the south of France with him talking about it. We let that go and started coming up with ideas for the second film instead of that. I think we did two and a half scripts and he turned them all down. He said, “Look, you go away and write television" and went ahead and did this film of the Punch and Judy man. That was effectively the break.

Tony apart from making that film did television as well for ITV and he didn’t get the writers. I think by that time he had stopped performing as such and memorising the lines. Because of a crash that he had in a motor car that rendered him unconscious for a few days and not able to learn his lines, and that was apparent on the week that we did The Blood Donor – he had idiot boards up – you can see his eyes in the wrong places, but he did it well. He was so relieved at not having to learn a script every week that he deliberately chose that path. So that was a downfall. And not having anyone to really understand what the character was about. People used to say he was aggressive but he was never aggressive unless he was kicked first. Or rebuked. But they weren’t very good scripts, and the drinking started going on and on and on. We all know what the end was eventually. I think Alan heard from him early in the morning once from Heathrow. He was on his way to Australia, he was pissed out of his mind. He said, “When I get back we’ll get together and do something and knock their eyes out.” Why he thought we would get together again I don’t know.

In the middle of all this Lesley Bricusse had got in touch with us and said, “I’ve written this play, would you write a book for it?” So we did. He had already written the music. And we wrote this and he flipped over and said, “God, you know what you’ve done here, don’t you? Every word of this is Hancock.” We said, “No it isn’t, every word of this is us. Hancock can’t sing and can’t dance and he hates the stage and he won’t want to do this.” He said, “Let me show it to him.” And Hancock can’t wait to do it. He starts taking singing lessons and dance lessons. We had a reconciliation meeting at the restaurant and unbeknown to us he had invited the press, who had buggered off by the time he got there because he was so late. That was the end of the possible reconciliation. Bricusse didn’t even bother to pursue the idea with someone else. So that was the last time we saw him.

- This extract is taken from Jasper Rees's interview with Ray Galton in 2005

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

Add comment