Schnittke Festival, Jurowski, Royal College of Music | reviews, news & interviews

Schnittke Festival, Jurowski, Royal College of Music

Schnittke Festival, Jurowski, Royal College of Music

Satire and tragedy meet in celebration of Russia's greatest late 20th-century composer

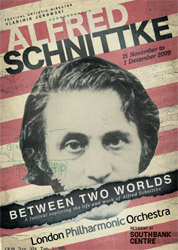

Whether or not you rate Vladimir Jurowski among the top 10 hardest-working, most inspirational conductors in the business – I do – you have to award him the palm for enterprise. His passionate involvement in youth projects of various kinds, and a quest for innovative programming that would send most concert managements running, combined in the launch of his latest festival centred around the work of a single composer.

He could have begun his exploration of Alfred Schnittke, Russia’s greatest maverick composer after Shostakovich, with full pomp in the Royal Festival Hall with the orchestra he has turned into the capital’s most challenging, the London Philharmonic. Instead he chose to raise the game of students at the Royal College of Music beyond their wildest dreams.

With Jurowski’s unique match of lyric flexibility and a rhythmic discipline manifest in the visual style of his conducting, the RCM Symphony and Chamber Orchestras could face comparison with the very best. Indeed, the shattering, iron-fist-in-velvet-glove interpretation of one of the 20th century’s most painful symphonies, Prokofiev’s Sixth, had far more to say than the puzzling reticence of Gergiev’s performance in a fitfully brilliant LSO Prokofiev series several seasons back.

It took the symphony to knit the strands of capricious satire and monochrome tragedy divided between the two Schnittke works of the first half. The Gogol Suite pieced together from an early theatre score by conductor Gennady Rozhdestvensky probably needed the narratives punctuating it from the Ukrainian master’s Dead Souls, The Overcoat and a devastating last will and testament. Sir Timothy Ackroyd’s low-key delivery, unhelpfully miked, froze audience and players into undue sobriety.

While the final obloquy moved us with its sombre poetic prose, the earlier passages were perhaps too long a diversion too soon in the evening. Jurowski was more successful in drawing from his bizarre ensemble the skull beneath Schnittke’s comic, pastiche skin. A waltz grinds frighteningly into the lower depths; a bizarre 19th-century ball scene breaks into galops, even a tango, with sounds that include the flailing metal bars of the flexatone. Even a few ringtones going off around the hall would not have been inappropriate; the more the merrier – which in Schittke’s case ultimately means the grimmer.

This is his celebrated "polystylism", a seemingly anarchic fusion of the serious and the popular which he puts together with underlying strength of purpose. Only the darker side remains in many of the later works, written between strokes and hanging on through sheer tenacity. It’s not easy to warm to the Monologue for viola and strings of 1989. Written for Yuri Bashmet, it follows the line of Shostakovich’s great Shakespearean monologues for Oistrakh and Rostropovich. By playing to Jurowski and his intense string colleagues in the RCM Chamber Orchestra rather than to the audience, Alexander Zemtsov emphasised the teamwork but seemed reticent in taking the spotlight, like an actor delivering his lines upstage. The final, desperate surges towards the light balanced the lower-register rumblings of the Gogol Suite but seemed like a long time in coming.

For those willing or able to keep faith with the tireless Jurowski and to stay on after the official end of the concert, the reward came with a true Schnittke masterpiece, the Concerto Grosso No 1 of 1977 which first converted many to the Russian’s frenetic genius. It was offered here as a generous bonus for the students to hear their colleagues’ work-in-progress before the official performance in the Southbank’s big Schnittke marathon next Sunday. Here was searing teamwork between violinists Hun-Ouk Park and the elfin Agata Darashkaite, able to smile when fierce pizzicato broke a string and a colleague quickly swapped violins with her. Their ultimate Corelli-on-speed duelling which breaks into another tango could only end in collapse and the same treated piano sounds - powerfully taken by Kumi Matsuo - we had heard at the end of the Suite.

For those willing or able to keep faith with the tireless Jurowski and to stay on after the official end of the concert, the reward came with a true Schnittke masterpiece, the Concerto Grosso No 1 of 1977 which first converted many to the Russian’s frenetic genius. It was offered here as a generous bonus for the students to hear their colleagues’ work-in-progress before the official performance in the Southbank’s big Schnittke marathon next Sunday. Here was searing teamwork between violinists Hun-Ouk Park and the elfin Agata Darashkaite, able to smile when fierce pizzicato broke a string and a colleague quickly swapped violins with her. Their ultimate Corelli-on-speed duelling which breaks into another tango could only end in collapse and the same treated piano sounds - powerfully taken by Kumi Matsuo - we had heard at the end of the Suite.

The Prokofiev symphony, like Schnittke’s late works, is the product of a composer debilitated by years of oppression and ill health. Here too the spirit shone through. If the inexorable goose steps and brass eruptions of the first movement flatten bittersweet introspection, and result in what the composer called the "asthmatic wheezing" of the horns – terrifyingly done here – then the Wagnerian breadth of the Largo allows the wounds to breathe. Jurowski heightened an almost unbearable emotion by linking its opening screams to the unquiet end of the first movement. He understands that if Prokofiev consciously evokes the agony of Wagner’s Amfortas, Tristan and love are here, too: tenderness and tension meet in the composer’s greatest slow movement.

After that, the jolly Soviet galop of the finale is only an illusion. Highlighting the threat of the underlying rhythms and passing discords, Jurowski drew dazzling articulation from the student string body, picking up with lightning reflexes on any slight lapse in ensemble. The overwhelming conclusion drives the galumphing rhythms to disaster. It’s the hardest of symphonic mood-swings to manage, but in the pauses between two more, climactic screams and in the silence he commanded from the audience after the final disastrous crash, Jurowski drove home the tragedy more powerfully than any conductor I have ever heard in this work. How wonderful that he had an adoring student orchestra to share the adventure.

- 'Between Two Worlds: Exploring the life and work of Alfred Schnittke' continues until 1 December. More information here.

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Classical music

Classical CDs: Hamlet, harps and haiku

Epic romantic symphonies, unaccompanied choral music and a bold string quartet's response to rising sea levels

Classical CDs: Hamlet, harps and haiku

Epic romantic symphonies, unaccompanied choral music and a bold string quartet's response to rising sea levels

Kolesnikov, Tsoy / Liu, NCPA Orchestra, Chung, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - transfigured playing and heavenly desire

Three star pianists work wonders, and an orchestra dazzles, at least on the surface

Kolesnikov, Tsoy / Liu, NCPA Orchestra, Chung, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - transfigured playing and heavenly desire

Three star pianists work wonders, and an orchestra dazzles, at least on the surface

BBC Proms: Láng, Cser, Budapest Festival Orchestra, Ivan Fischer review - idiomatic inflections

Bartók’s heart of darkness follows Beethoven’s dancing light

BBC Proms: Láng, Cser, Budapest Festival Orchestra, Ivan Fischer review - idiomatic inflections

Bartók’s heart of darkness follows Beethoven’s dancing light

Weilerstein, NYO2, Payare / Dueñas, Malofeev, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - youthful energy and emotional intensity

Big-boned Prokofiev and Shostakovich, cacophonous López, plus intense violin/piano duo

Weilerstein, NYO2, Payare / Dueñas, Malofeev, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - youthful energy and emotional intensity

Big-boned Prokofiev and Shostakovich, cacophonous López, plus intense violin/piano duo

theartsdesk at the Three Choirs Festival - Passion in the Cathedral

Cantatas new and old, slate quarries to Calvary

theartsdesk at the Three Choirs Festival - Passion in the Cathedral

Cantatas new and old, slate quarries to Calvary

BBC Proms: Estonian Philharmonic Chamber Choir, Kaljuste review - Arvo Pärt 90th birthday tribute

Stillness and contemplation characterise this well sung late-nighter

BBC Proms: Estonian Philharmonic Chamber Choir, Kaljuste review - Arvo Pärt 90th birthday tribute

Stillness and contemplation characterise this well sung late-nighter

BBC Proms: Kholodenko, BBCNOW, Otaka review - exhilarating Lutosławski, underwhelming Rachmaninov

Polish composers to the fore in veteran conductor’s farewell

BBC Proms: Kholodenko, BBCNOW, Otaka review - exhilarating Lutosławski, underwhelming Rachmaninov

Polish composers to the fore in veteran conductor’s farewell

theartsdesk at the Pärnu Music Festival 2025 - Arvo Pärt at 90 flanked by lightness and warmth

Paavo Järvi’s Estonian Festival Orchestra still casts its familiar spell

theartsdesk at the Pärnu Music Festival 2025 - Arvo Pärt at 90 flanked by lightness and warmth

Paavo Järvi’s Estonian Festival Orchestra still casts its familiar spell

BBC Proms: Batsashvili, BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra, Ryan Wigglesworth review - grief and glory

Subdued Mozart yields to blazing Bruckner

BBC Proms: Batsashvili, BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra, Ryan Wigglesworth review - grief and glory

Subdued Mozart yields to blazing Bruckner

Classical CDs: Hens, Hamburg and handmaids

An unsung French conductor boxed up, plus Argentinian string quartets and baroque keyboard music

Classical CDs: Hens, Hamburg and handmaids

An unsung French conductor boxed up, plus Argentinian string quartets and baroque keyboard music

BBC Proms: McCarthy, Bournemouth SO, Wigglesworth review - spring-heeled variety

A Ravel concerto and a Walton symphony with depth but huge entertainment value

BBC Proms: McCarthy, Bournemouth SO, Wigglesworth review - spring-heeled variety

A Ravel concerto and a Walton symphony with depth but huge entertainment value

BBC Proms: First Night, Batiashvili, BBCSO, Oramo review - glorious Vaughan Williams

Spirited festival opener is crowned with little-heard choral epic

BBC Proms: First Night, Batiashvili, BBCSO, Oramo review - glorious Vaughan Williams

Spirited festival opener is crowned with little-heard choral epic

Add comment