What Is Beauty?, BBC Two | reviews, news & interviews

What Is Beauty?, BBC Two

What Is Beauty?, BBC Two

Matthew Collings dissects beauty only to find the process provides the answer

As questions go, "What is beauty?" is quite possibly only second to "What do women want?" in the frequency of its asking and in the difficulty of its answer. As the first programme in BBC Two and BBC Four’s Modern Beauty season, What Is Beauty? features Matthew Collings skirting around the edges of an answer and in doing so inadvertently hitting upon one.

Collings tries to identify ten different components of beauty with reference to some of his favourite artworks. Piero della Francesca’s Madonna del Parto from Monterchi is beautiful because of its simplicity, Robert Rauschenberg’s Charlene because its components are carefully selected, Norman Foster’s Millau Bridge because it returns to nature.

He travels around Europe (presumably the recession put paid to an American jaunt), from the new Brandhorst Museum in Munich to the gilded Norman Monreale Cathedral in Sicily, to illustrate these points.

From a technical perspective, there is not much wrong with the show, although he does tend to over-address the viewer ("you" should do this, "you" can do that), as if we actively need to be engaged.

But it is his argument which is pointed in the wrong direction. When Socrates asked people, "What is bravery?" and they responded (according to Plato) with examples like "running into a burning building to save a child" or "fighting well in battle", he pointed out that they were giving him accidents of bravery, not a definition of it. It is exactly the same here: Collings’s ten factors are accidents of beauty, not a definition of beauty.

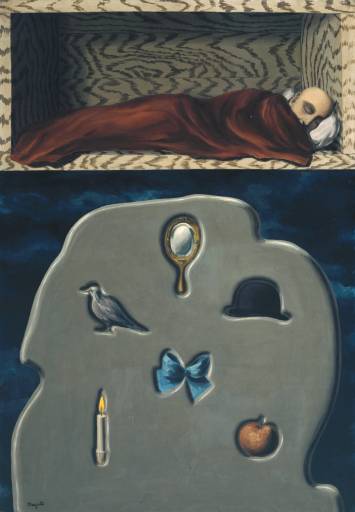

So Magritte’s Reckless Sleeper (in the Tate) may be beautiful because it is surprising (another factor), with its sleeping man and the banal tokens of everyday life in an amorphous grey dream below, but what about a work that is not surprising (eg a still life of fruit)? Collings says something is beautiful because it tries to (or just does) imitate nature, but what about the unnatural idea of acceleration? Art Deco is concerned with mechanics, rejecting the natural.

So Magritte’s Reckless Sleeper (in the Tate) may be beautiful because it is surprising (another factor), with its sleeping man and the banal tokens of everyday life in an amorphous grey dream below, but what about a work that is not surprising (eg a still life of fruit)? Collings says something is beautiful because it tries to (or just does) imitate nature, but what about the unnatural idea of acceleration? Art Deco is concerned with mechanics, rejecting the natural.

The problem is that for every factor Collings suggests is beautiful, its absence or its opposite can be equally beautiful. He implicitly admits this too. At the end of the programme, he urges you to make your own list of what is beautiful, but what I find beautiful may not fit into his categories, or if it does, it may be entirely opposed to them. There are limitless categories, and we all find different things beautiful. Collings does not address or even seem to understand that we will not all agree with him: beauty, if it is anything, is relative.

Despite the relativity of these factors, Collings does help us to answer "What is beauty?" What he is doing is asking questions, which in turn cause us to know more and thus gain a greater appreciation, which is surely what makes something beautiful: our understanding of it. The more you know about the technique Monet used or the subject of Guernica or the materials of the Parthenon, the more likely you are to understand the work and find it beautiful because you comprehend its complexity and the intelligence behind it.

So, instead of saying that something which adheres to nature is beautiful, he should say, "What was the artist intending to say about nature with this work?" The answer could be something or nothing, but in asking it, we learn a little more and will think more about the picture. Don’t ask "Is this Jackson Pollock patterned?" (as he does) but "Why was Jackson Pollock trying to create (or avoid) pattern?"

So, instead of saying that something which adheres to nature is beautiful, he should say, "What was the artist intending to say about nature with this work?" The answer could be something or nothing, but in asking it, we learn a little more and will think more about the picture. Don’t ask "Is this Jackson Pollock patterned?" (as he does) but "Why was Jackson Pollock trying to create (or avoid) pattern?"

The answers to these questions cannot necessarily be found in the pictures – a study of history and biography and art history and psychology and pop culture will help us answer them. This then leads to the perhaps perverse conclusion that the question "What is beauty?" is best answered not by looking at beautiful things (such as in a TV documentary) but by reading: the surface becomes deeper when you know more.

But what about when one first looks at a picture and is struck dumb by its beauty? For example, new artists I know nothing about can stop me in my tracks with the appearance of their work. A Raphael Christ made me cry. If this is anything, it is art touching our emotions. We do not consider its spontaneity (another factor) or relationship with nature but there is an almost atavistic reaction: this is emotional, mental, psychological – not words which get much play in Collings’ film. His factors try to intellectualise these emotional experiences, but their intellectual dimension is not quite enough either.

One further complaint is that he also hardly touches on any art form but painting: there is the Laocoon sculpture and Matisse’s paper snail, but what about photography and film? Do these have their own kinds of beauty? If we follow Collings, we could find different types of beauty in them: the truth of a photo (but a staged one can be beautiful too), a film of a meadow (but not one of a city?).

Collings sets out to answer "What is beauty?" but the best answer to this that he provides is implicit in his questioning, not explicit in his answers.

Comments

...

...

...

...

...

...

...

...

...

...

...

...

...

...