Interview: 10 Questions for LFF Director Clare Stewart | reviews, news & interviews

Interview: 10 Questions for LFF Director Clare Stewart

Interview: 10 Questions for LFF Director Clare Stewart

The London Film Festival's director wants to reshape the way October's annual jamboree engages with its audience

Clare Stewart arrived in London from Australia a year ago this month, into one of the biggest jobs in the UK film industry. For film buffs, it might seem like she entered a giant playground, a job to die for.

It’s a massive remit, but one for which Stewart’s 17 years in the film business makes her unusually well-suited. Immediately prior to coming to London she was the director of the Sydney Film Festival, for five years; before that, she was the first head of film programs at the Australian Centre for the Moving Image, in Melbourne. So she’s effectively done both sides of her current job; any questions about how she could possibly combine them evaporate when meeting someone whose passion is contagious.

Stewart is a woman with a mission, to reshape the way in which film festivals engage with the audience. During her time in Sydney she introduced an official competition for films that are “courageous, audacious and cutting-edge”, as well as a documentary prize. She also scaled down the length of the festival and the number of films shown (novel in itself, in an environment that tends towards excess), while presenting the selection in a new way, through snappily titled and accessible themes rather than national or genre categories. As a result, 31percent of the festival’s audience in 2009 and 2010 attended the festival for the first time, with a substantial growth in younger audiences.

She’s attempting a similar shake-up in London, with films clustered around the themes of Love, Debate, Dare, Laugh, Thrill, Cult, Journey, Sonic and Family, with each strand featuring its own gala screening. As BFI chief executive Amanda Neville declared at the launch of the programme, Stewart has shown “a wonderful disregard for the rule book.” It’s not without its risk, of course; habit is a tough thing to break.

She was born in the Melbourne suburb of Moonee Ponds, which she cheerfully tells me is the home of a certain Dame Edna Everage, but grew up in Korumburra, also in Victoria.

DEMETRIOS MATHEOU: Can you recall the film, or films, that inspired you to pursue a career in cinema?

CLARE STEWART: I grew up in a small town without a cinema, and my dad would frequently banish the television to the garden shed, so it wasn’t until university that I discovered my grand passion. I can’t remember the precise order, but it was discovering Dziga Vertov’s Man with a Movie Camera and Howard Hawks’ His Girl Friday in Cinema Studies 101, at the same time as falling in love with Eric Rohmer’s Boyfriends and Girlfriends at my local arthouse cinema. These films and many others started to shape my understanding that I’d found something that I never wanted to abandon. But it was probably E.T. at the Leongatha Drive-In that awakened me to the power of film.

CLARE STEWART: I grew up in a small town without a cinema, and my dad would frequently banish the television to the garden shed, so it wasn’t until university that I discovered my grand passion. I can’t remember the precise order, but it was discovering Dziga Vertov’s Man with a Movie Camera and Howard Hawks’ His Girl Friday in Cinema Studies 101, at the same time as falling in love with Eric Rohmer’s Boyfriends and Girlfriends at my local arthouse cinema. These films and many others started to shape my understanding that I’d found something that I never wanted to abandon. But it was probably E.T. at the Leongatha Drive-In that awakened me to the power of film.

You were running the Sydney Film Festival, very successfully. What compelled you to leave Australia and tackle London?

Geography is limiting, it closes choices down to special interest

I had a great and very productive time at Sydney, but when the programme for my fifth festival came back from the printer I could sense a certain level of satisfaction and comfort sneaking in. So it was time to invite change. Spookily, I saw the ad for the BFI job the night before we announced I was stepping down as Sydney’s festival director. I was on the plane to London for the interview two days after Sydney’s closing night.

It was the role itself that attracted me, since it combines both festival direction and year-round venue programming, which comes with the chance to engage with the audience every day and different kinds of creative opportunity. London was a pretty decent bonus of course, that and the fact that the BFI is like a film culture magnet, which I’d been drawn to since the days I was a research assistant filing tatty old copies of Monthly Film Bulletin at the Australian Film Institute’s library in South Melbourne.

If this were football, I’d imagine a degree of outrage at the choice of an Australian manager! Would you say your being Australian is irrelevant? Or can you bring a different and valuable cultural perspective to bear?

But everybody knows Australians are good at football, right?! If there’s any benefit to being an outsider, I’d say that my positivity for the future of film in the UK is undiluted and raw. As for being Australian, I frequently get described as "direct" or, my personal favourite, "bubbly and no-bullshit". Perhaps it’s easier to take risks and create change because of that; or perhaps it has nothing to do with anything.

You’ve been here for a year now. So what have you learned about London audiences? Is there something that marks them out from filmgoers in Melbourne or Sydney or anywhere else in the world?

You’ve been here for a year now. So what have you learned about London audiences? Is there something that marks them out from filmgoers in Melbourne or Sydney or anywhere else in the world?

BFI Southbank and both festivals – the LFF and the London, Lesbian & Gay Film Festival – have extremely loyal and savvy audiences. The committed cinephile craves depth, and the BFI is superbly placed to provide great context around the films we screen, especially through our archive. But we also attract a lot of casual moviegoers who dip into the programme more occasionally. The decision to take the LFF out to more borough venues was informed by the fact that London is a city with many bustling centres, and we want to open up the festival for people who are more inclined to venture to their local cinema.

For me, a film festival is like temporary housing for a swarm of restless spirits

What are the biggest changes we can expect to see this year? What is the Stewart stamp?

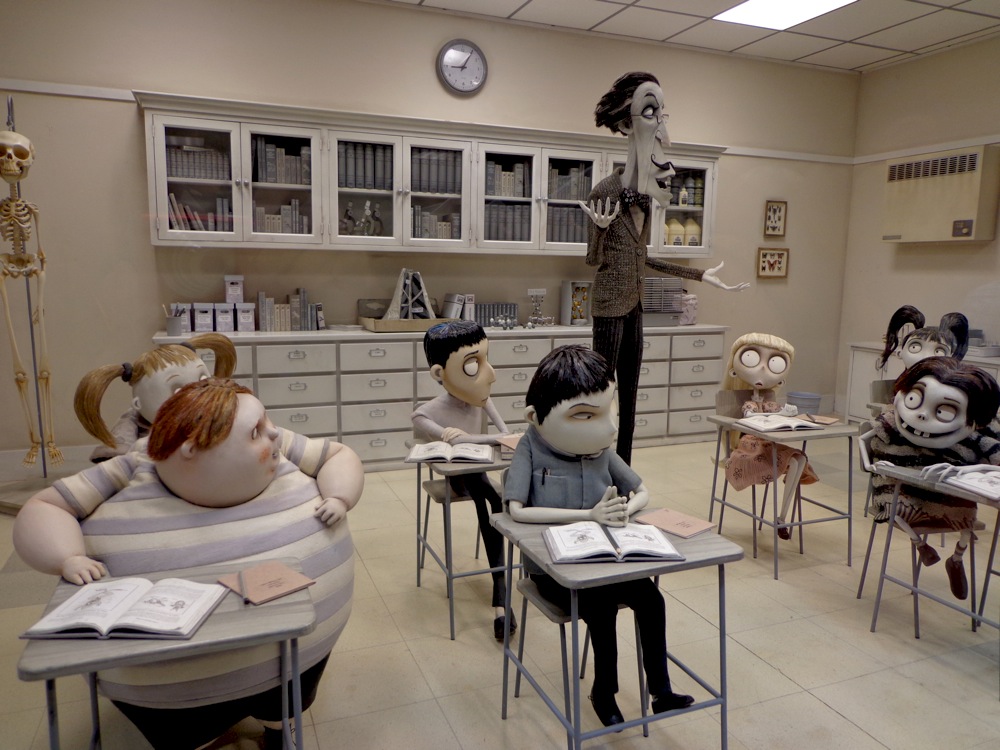

We have made four big changes to the programme and festival structure, all aimed at growing our audience and increasing our profile in the UK and internationally: the introduction of official competition sections for the best film, best first feature and best documentary; the introduction of new programme categories, moving away from geographical borders towards thematic sections; cine-casting our opening night premiere of Frankenweenie (pictured above) and our American Express Gala of Brett Morgen’s documentary Crossfire Hurricane to screens across the UK, with live links, respectively, to Tim Burton and his cast, and the Rolling Stones; shortening the festival to 12 days and taking it out to more screens across London.

Watch the trailer to Crossfire Hurricane

Tell me about the thinking behind these new sections. Is the traditional method of grouping films geographically past its sell-by date in our increasingly global environment?

What excites me about what I do is connecting films and filmmakers with audiences. So I’m interested in what influences choice, and in how to make the selection of over 200 films navigable in a way that is enticing and unexpected for both committed festival goers and new audiences. Geography is limiting, it closes choices down to special interest, gives us only one point of entry; in contrast, thinking of how and what we experience when we go to the movies is much more expansive and provides more scope to be playful, and also serious with the programming mix.

Audience research shows that “what the film is about” and genre inform our choices more than which stars are in it, word-of-mouth and reviews. So the idea with this approach is to open that up, invent categories that appeal without being reductive, and that provide enough scope to be textured and surprising. In Love, for example, you can see Michael Haneke’s Palme d’Or winner Amour (pictured above left) alongside Liz Garbus’s wonderful documentary Love, Marilyn about Marilyn Munroe and the gentle and surprising Danish film Teddy Bear, about a 38-year-old body builder who lives at home with his manipulative mother.

Audience research shows that “what the film is about” and genre inform our choices more than which stars are in it, word-of-mouth and reviews. So the idea with this approach is to open that up, invent categories that appeal without being reductive, and that provide enough scope to be textured and surprising. In Love, for example, you can see Michael Haneke’s Palme d’Or winner Amour (pictured above left) alongside Liz Garbus’s wonderful documentary Love, Marilyn about Marilyn Munroe and the gentle and surprising Danish film Teddy Bear, about a 38-year-old body builder who lives at home with his manipulative mother.

Can you give a few examples from the programme, including events, which somehow epitomise the spirit of this year’s festival?

For me, a film festival is like temporary housing for a swarm of restless spirits – any attempt to reduce it to the singular would prove elusive and unrewarding. You could say this year’s festival has the glamorous intensity of Marion Cotillard, the political acuity of [Oscar-winning documentary maker] Alex Gibney, the storytelling virtuosity of Salman Rushdie, the daring demeanour of Viggo Mortensen and the intellectual rigour of Slavoj Zizek. Since they are all participating in Screen Talks or In Conversation events at the festival, that would actually be true.

One of the biggest thrills of attending a film festival is that of discovery: the movie that has arrived unheralded, out of nowhere, and astounds you. Can you think of one or two of your own? Your most electric film festival moments, as a punter?

Funnily enough, one of my favourite discoveries occurred during the Melbourne International Film Festival, but it wasn’t a festival screening. After I’d seen six films already that day, a friend suggested we go to a midnight screening at Chinatown Cinemas. We had no idea what we were going to see, we were just cinema addicts looking for a late-night fix. The film was Wong Kar-wai’s Days of Being Wild, and it remains one of my favourite films of all time.

This year, that kind of moment was experienced by an entire audience, I think, when Beasts of the Southern Wild (pictured right) premiered in Sundance. I’m thrilled we are presenting its UK premiere in the extraordinary line-up for our first feature competition. It still feels so rare to behold a film that exceeds your sense of cinema, a film that escapes you and embraces you at the same time.

This year, that kind of moment was experienced by an entire audience, I think, when Beasts of the Southern Wild (pictured right) premiered in Sundance. I’m thrilled we are presenting its UK premiere in the extraordinary line-up for our first feature competition. It still feels so rare to behold a film that exceeds your sense of cinema, a film that escapes you and embraces you at the same time.

What’s your biggest fear? What’s the worst thing that can happen in the next fortnight?

That I will forget to set my alarm. Seriously though, it is essential to be fearless, otherwise something will go wrong.

Any tips for London filmgoers on navigating and getting the best out of the 56th edition?

Go to every film in one section, or one film in every section.

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Film

Can I get a Witness? review - time to die before you get old

Ann Marie Fleming directs Sandra Oh in dystopian fantasy that fails to ignite

Can I get a Witness? review - time to die before you get old

Ann Marie Fleming directs Sandra Oh in dystopian fantasy that fails to ignite

Happyend review - the kids are never alright

In this futuristic blackboard jungle everything is a bit too manicured

Happyend review - the kids are never alright

In this futuristic blackboard jungle everything is a bit too manicured

Robert Redford (1936-2025)

The star was more admired within the screen trade than by the critics

Robert Redford (1936-2025)

The star was more admired within the screen trade than by the critics

Blu-ray: The Sons of Great Bear

DEFA's first 'Red Western': a revisionist take on colonial expansion

Blu-ray: The Sons of Great Bear

DEFA's first 'Red Western': a revisionist take on colonial expansion

Spinal Tap II: The End Continues review - comedy rock band fails to revive past glories

Belated satirical sequel runs out of gas

Spinal Tap II: The End Continues review - comedy rock band fails to revive past glories

Belated satirical sequel runs out of gas

Downton Abbey: The Grand Finale review - an attemptedly elegiac final chapter haunted by its past

Noel Coward is a welcome visitor to the insular world of the hit series

Downton Abbey: The Grand Finale review - an attemptedly elegiac final chapter haunted by its past

Noel Coward is a welcome visitor to the insular world of the hit series

Islands review - sunshine noir serves an ace

Sam Riley is the holiday resort tennis pro in over his head

Islands review - sunshine noir serves an ace

Sam Riley is the holiday resort tennis pro in over his head

theartsdesk Q&A: actor Sam Riley on playing a washed-up loner in the thriller 'Islands'

The actor discusses his love of self-destructive characters and the problem with fame

theartsdesk Q&A: actor Sam Riley on playing a washed-up loner in the thriller 'Islands'

The actor discusses his love of self-destructive characters and the problem with fame

Honey Don’t! review - film noir in the bright sun

A Coen brother with a blood-simple gumshoe caper

Honey Don’t! review - film noir in the bright sun

A Coen brother with a blood-simple gumshoe caper

The Courageous review - Ophélia Kolb excels as a single mother on the edge

Jasmin Gordon's directorial debut features strong performances but leaves too much unexplained

The Courageous review - Ophélia Kolb excels as a single mother on the edge

Jasmin Gordon's directorial debut features strong performances but leaves too much unexplained

Blu-ray: The Graduate

Post #MeToo, can Mike Nichols' second feature still lay claim to Classic Film status?

Blu-ray: The Graduate

Post #MeToo, can Mike Nichols' second feature still lay claim to Classic Film status?

Add comment