Wild Thing: Epstein, Gaudier-Brzeska, Gill, Royal Academy | reviews, news & interviews

Wild Thing: Epstein, Gaudier-Brzeska, Gill, Royal Academy

Wild Thing: Epstein, Gaudier-Brzeska, Gill, Royal Academy

The riveting force of British Modernist sculpture

By all accounts Eric Gill had a shocking private life.

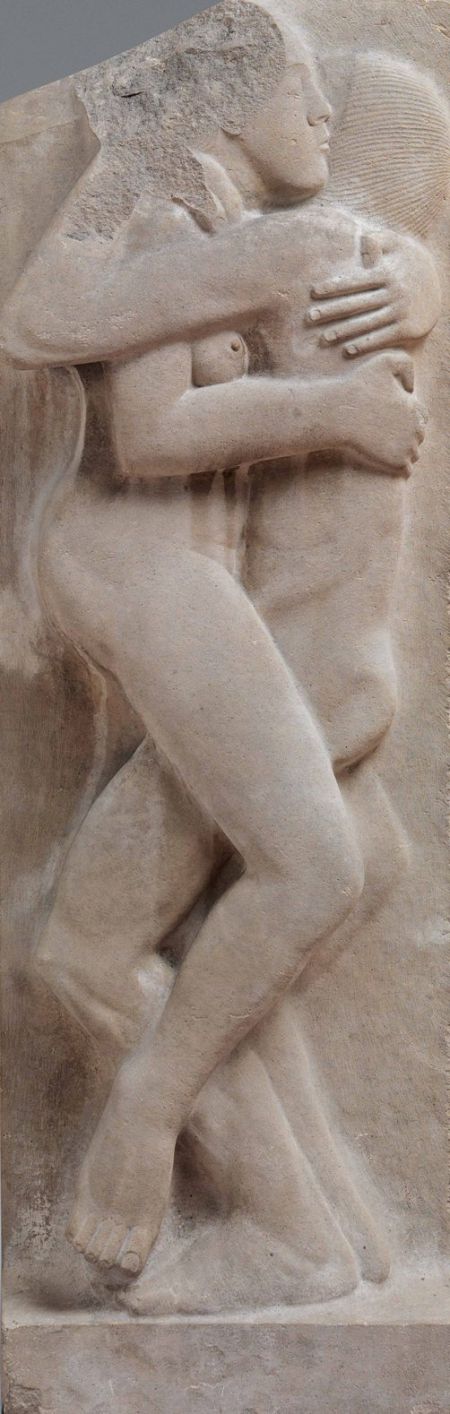

But as much as Gill’s personal life appals and fascinates, we are schooled to separate the artist from the person, and this is what the Royal Academy’s riveting exhibition of three modernist masters of British sculpture achieves. Ignoring salacious detail, we’re given only a sober account of Ecstasy (1910-11, picture right), which depicts in Portland stone relief, and with elegant simplicity, Gill’s sister Gladys making love to her husband, portrayed from a life "sitting". Unsurprisingly shocking for its time, Gill’s London gallery, the Chenil Gallery in Chelsea, decided against putting the sculpture on display for his first solo exhibition in 1911, though the it did not languish in obscurity: it was bought by Edward Warren, an English collector who’d commissioned Rodin’s The Kiss some years earlier.

But as much as Gill’s personal life appals and fascinates, we are schooled to separate the artist from the person, and this is what the Royal Academy’s riveting exhibition of three modernist masters of British sculpture achieves. Ignoring salacious detail, we’re given only a sober account of Ecstasy (1910-11, picture right), which depicts in Portland stone relief, and with elegant simplicity, Gill’s sister Gladys making love to her husband, portrayed from a life "sitting". Unsurprisingly shocking for its time, Gill’s London gallery, the Chenil Gallery in Chelsea, decided against putting the sculpture on display for his first solo exhibition in 1911, though the it did not languish in obscurity: it was bought by Edward Warren, an English collector who’d commissioned Rodin’s The Kiss some years earlier.

The first gallery in the RA’s exhibition is devoted to Gill, with the second to Jacob Epstein and the third to Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, the trio of young, radical sculptors – the latter two émigrés from New York and Orléans, respectively – who transformed British sculpture in the decade leading up to the First World War. This they did by returning to the art of carving directly in stone in a manner that evoked primitive and ethnographic art. And what strikes you about this first room, which belies anything you might assume of Gill as monstrous abuser, is the sensual tenderness, the almost sweetly sentimental eroticism that pervades much of his work, from the explicitly sexual to the overtly religious. Austere in their economy of execution but voluptuous in form, his numerous free-standing Mother and Child figures, for instance, convey both a sense of the devoutly holy and the earthily seductive.

Gill’s carvings are executed with a pared-down economy that make him truly modern, yet they possess none of the charged aggression and forceful energy of the work of either Epstein or Gaudier-Brzeska. They are objects of stillness and serenity, and even in Boxers (1913), a relief in which we see two young naked boys engaged in the tense embrace of two fighters, there is a sense of a sombre, slow, ritualised dance, which is more suggestive of tender foreplay than of sweaty physical combat.

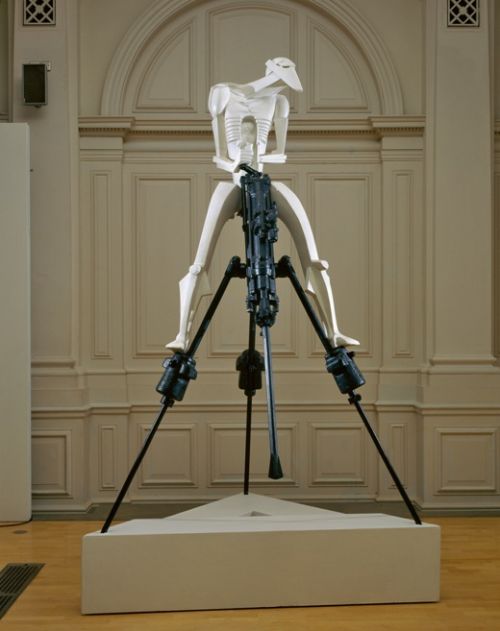

As bold as Gill was, Epstein was bolder and more radical still, and it is he, rather than Gill, with his traditional, return-to-medieval craftsmanship, who can be said to be the true father of British Modernist sculpture. In the second gallery we are confronted by the striking figure of the Rock Drill (picture left), seen here in its original full-length form (recreated in the 1970s). A sinister, helmet-faced robotic figure straddles a real rock drill, and in a perversion of the traditional theme of mother and child that Gill was so attached to, this dehumised figure carries within its open abdominal cavity an upright foetus. It is a breathtakingly audacious piece of work, more powerful and fearsomely majestic than the slightly later truncated figure of the Rock Drill we see beside it, cast in bronze and minus legs and drill. The original was completed in 1915. No other British sculpture of the period conveys such a brutal sense of the technological armeggedon of the First World War.

As bold as Gill was, Epstein was bolder and more radical still, and it is he, rather than Gill, with his traditional, return-to-medieval craftsmanship, who can be said to be the true father of British Modernist sculpture. In the second gallery we are confronted by the striking figure of the Rock Drill (picture left), seen here in its original full-length form (recreated in the 1970s). A sinister, helmet-faced robotic figure straddles a real rock drill, and in a perversion of the traditional theme of mother and child that Gill was so attached to, this dehumised figure carries within its open abdominal cavity an upright foetus. It is a breathtakingly audacious piece of work, more powerful and fearsomely majestic than the slightly later truncated figure of the Rock Drill we see beside it, cast in bronze and minus legs and drill. The original was completed in 1915. No other British sculpture of the period conveys such a brutal sense of the technological armeggedon of the First World War.

It was a war that, earlier that year, had killed his 23-year-old friend Gaudier-Brzeska, whom he had met in 1911 and for whom he acted as a mentor. The gallery devoted to Gaudier-Brzeska recalls the primitivist and totemic work of Brancusi, yet with even greater animalistic energy. His Portrait of Ezra Pound (1914) portrays the poet as an abstracted totem carved in rough-hewn wood that suggests a overpowering and brutish individual, and his iconic Red Stone Dancer (c.1913) radiates a kind of orgiastic force.

Both Epstein and Gaudier-Brzeska were the true revolutionaries of British sculpture, but never for a moment does their work in this exhibition overshadow the subtle work of Gill, an artist who is rarely exhibited in their company. The exhibition does, in fact, strikingly illustrate the divergent forces of British Modernism, but in a way that is beautifully and mutually complementary.

Wild Thing: Epstein, Gaudier-Brzeska, Gill continues at the Royal Academy until 24 January 2010. More information here.

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Photo Oxford 2025 review - photography all over the town

At last, a UK festival that takes photography seriously

Photo Oxford 2025 review - photography all over the town

At last, a UK festival that takes photography seriously

![SEX MONEY RACE RELIGION [2016] by Gilbert and George. Installation shot of Gilbert & George 21ST CENTURY PICTURES Hayward Gallery](https://theartsdesk.com/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail/public/mastimages/Gilbert%20%26%20George_%2021ST%20CENTURY%20PICTURES.%20SEX%20MONEY%20RACE%20RELIGION%20%5B2016%5D.%20Photo_%20Mark%20Blower.%20Courtesy%20of%20the%20Gilbert%20%26%20George%20and%20the%20Hayward%20Gallery._0.jpg?itok=7tVsLyR-) Gilbert & George, 21st Century Pictures, Hayward Gallery review - brash, bright and not so beautiful

The couple's coloured photomontages shout louder than ever, causing sensory overload

Gilbert & George, 21st Century Pictures, Hayward Gallery review - brash, bright and not so beautiful

The couple's coloured photomontages shout louder than ever, causing sensory overload

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Add comment