theartsdesk Q&A: Musician Django Bates, Part 2 | reviews, news & interviews

theartsdesk Q&A: Musician Django Bates, Part 2

theartsdesk Q&A: Musician Django Bates, Part 2

The jazz musician and composer talks craftsmanship, critics and pop music without control filters

Django Bates ascribes the variety of musical influences at play in his work to his childhood - growing up listening to his father's remarkably eclectic record collection. In the first part of my conversation with Django, he talks about Loose Tubes, StoRMChaser and his new post at Bern University of the Arts.

PETER QUINN: Your father’s record collection included Romanian folk music, African music, jazz. I’m intrigued to know how that music crossed his radar.

DJANGO BATES: Well, good question. I’ve just seen him a few minutes ago - he lives here. I think someone should interview him, because I can never get the answers. I’d be fascinated to know. He listened to Louis Armstrong (pictured below left) as a child. I heard him describing that as a complete epiphany, to be growing up in Lancashire, in a working-class family without much around in the way of culture, books and sounds.

Whereabouts in Lancashire?

Whereabouts in Lancashire?

Kirkham, which is near Preston I think. The shock of hearing that sound: it was like somebody speaking to him. But how he got from there to broadening out, and how he ended up in London, all of that's a mystery to me. I shall ask.

Could you identify from that period any epiphanies you had in terms of listening to recorded music?

It was different for me because I didn’t grow up in a house without sound and then suddenly stumble on a 78 and all of that. It was the opposite. I didn’t know that life existed without music around you. I was born in that house in Beckenham and I can picture the room I was born in and I would be very sure that my father would have played that Charlie Parker record on that day at some point. So it really is from being inside the womb and hearing that music, it was right there at the very beginning. Parker was probably as contemporary as it got for jazz stuff, I think. No, Charles Mingus.

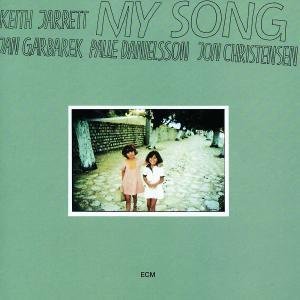

My Song was quite an eye opener because, especially with Jan Garbarek, it was playing in a jazz context but using a series of notes that didn’t remind me of anybody else I’d heard

But there have been epiphanies: Weather Report, for their textures. Steve Berry, the bass player, introduced me to Weather Report and that was round about the time I was realising that I needed to use keyboards as there were very few pianos around in the kind of gigs I was doing. Also the way that he encompassed folk and jazz and all of that - it was nice to see that it could be done. I suppose I had tried to do that but hadn’t felt that it had worked. And then Steve Berry also introduced me to the album My Song, Keith Jarrett and Jan Garbarek. And that was quite an eye opener because, especially with Jan Garbarek, it was playing in a jazz context but using a series of notes that didn’t remind me of anybody else I’d heard.

Was your mother a keen listener as well?

Was your mother a keen listener as well?

My mother was into the jazz scene, the kind of trad jazz or whatever it was meant to be called in London. More into that and the party vibe around that. She was less clear about what she got from music and it wasn’t her that put together a collection or went out and bought specific things. But she was very involved in a different way, which was to get me to lessons, so it was obviously important to her to hear me playing music, actually more than to buy other people’s music. I was in the London Schools Symphony Orchestra, playing trumpet, and she loved all that.

Were there any important pieces that you remember from that time?

It all had an impact, to be sitting in an orchestra. The things I remember would be Benjamin Britten’s Sea Interludes – just the power to illustrate things through music - and the Grieg Piano Concerto for its beautiful harmonies and textures. I enjoyed it all really. Just devouring sounds and learning.So that sensation of being surrounded by musicians stems from childhood?

Yes. I would have been about 11 when I got into that Concert Band as they called it, that was just brass instruments. And then it became the Training Orchestra and then the London Schools Symphony Orchestra. But when I came to write for orchestra, all of that made it much easier because I had some feeling of affinity with an orchestra and what it’s like to sit in the middle. What it’s like to be there when different sections are rehearsing stuff which is really difficult or challenging and to know why they’re difficult and challenging.

When people talk about your influences, you see the same names cropping up like Zawinul, Hermeto Pascoal, Jarrett. One name that I’ve never seen, who I feel is significant in terms of the way you layer your material, is Stravinsky. Is he an important touchstone for you?

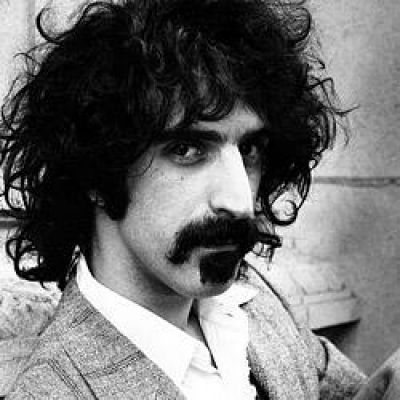

I see him as completely one of a kind and I can hear his music when you say his name. And he’s not part of a school, he’s just like Frank Zappa (pictured left), in a way. So from that point of view it’s in my musical vocabulary. I can’t think of any direct way. The way I feel is that everything I’ve heard is in the bank somewhere and at some point, if it’s useful, it comes out in some form or gets used, not re-created, but its effect is allowed out and that includes the kind of music that I don’t necessarily relate to particularly.

I see him as completely one of a kind and I can hear his music when you say his name. And he’s not part of a school, he’s just like Frank Zappa (pictured left), in a way. So from that point of view it’s in my musical vocabulary. I can’t think of any direct way. The way I feel is that everything I’ve heard is in the bank somewhere and at some point, if it’s useful, it comes out in some form or gets used, not re-created, but its effect is allowed out and that includes the kind of music that I don’t necessarily relate to particularly.

That’s interesting, I was expecting you to say “Stravinsky? Yes, of course”.

I think of that track “Delightful Precipice”.

Yes, exactly. Or “Food for Plankton” or “The Loneliness of Being Right” - all those superimposed layers and the irony of the music as well. It seems so Stravinskian to me.

The thing I like most about Zappa is his way of being an artist, his words and his steadfastness

Well, that’s good. No one’s mentioned that before. People quite often say Zappa and I say, well, I didn’t really ever hear him until very late on and I can see certain, slightly superficial, similarities maybe. The thing I like most about Zappa is his way of being an artist, his words and his steadfastness and all of that, it’s very interesting. And the fact he was able to survive doing something very anti-authoritarian in America at that time, required him to be very clever and on the case.

You're not someone who appears to agonise over artistic decisions. Is anything OK in your world?

That’s really hard to answer because it’s not a case of anything being OK, but it is the case that nothing is banned. I’ve got a set of principles about composing, some of which are probably quite clear and easy to describe and some which are maybe a bit obscure. Things like: I’m always aware how well crafted something is, either that I’m writing or working on, or something I hear of someone else’s.

I’m really interested in the idea of craftsmanship. Growing up, my Dad was doing a lot of carpentry and I was given a work bench as a young kid as a birthday present and some chisels and mallets - quite a dangerous gift, really. And my Dad taught me at that point: never cut towards yourself, that’s the one rule. And that's one of the few pieces of advice he’s ever given me and it’s bloody good! It works when cooking, you know, anything. I see making music as really quite similar to, actually, that [Django points to a wooden sculpture hanging on the wall]. You know, getting something out of wood and every single part of it will be noticed, will be seen and felt.So even at its most complex, where the textures are almost at breaking point, in your head you want all of those lines to be heard and to be parsed?

Making music was my most direct way of communicating with people, it felt like that to me anyway

It may be that the human ear can’t hear them all but I’ve got to be able to justify to myself all of them, all of the notes. The other element in all of this is the audience. At some point, quite early on, I decided that when I was writing music or playing music, the audience were to be involved in that process in a big way. In fact making music was my most direct way of communicating with people, it felt like that to me anyway. And so everything I’m writing, on some level I’m imagining what effect it has on someone who’s never heard it before – and getting to the end of a piece, there’s been that slight disappointment that I’ll never hear it the way it’s meant to be heard, ie, with a completely fresh set of ears and no knowledge of what it’s all about and how it works. But after a while you stop worrying about that and you just trust that you know how to play with the audience’s expectations and use those to make an exciting experience for them, or a moving experience for them. I’m also in the audience so it’s for me as well.

That seems so intuitive and yet not everyone does that.

Definitely not. I mean, I work with a lot of young composers who are studying composition and I can see often that isn’t yet part of the plan, it’s just a struggle to be making marks on paper really. I suppose you have to do a lot of it before you get past that physical stage of, oh, I’m making marks on paper and I wonder what they’re going to sound like, to a point where, let’s say, I’ve got a trio, we are going to record in a month’s time, there’s one certain kind of tempo that would be really nice to play in, we don’t have anything, so there’s my reason to write and I can sit down and I can fill the gap. That’s enough of a reason to write.

And similarly, just as you’ve got the audience in your head when you’re composing, you’re fortunate to have amazing performers who you’ve worked with throughout your career. Do you also hear them playing the music in your head?

Yeah. I might also think: oh, this person isn’t getting much room in this band so far and they do a really nice thing on this area of their instrument. That seems like a gap. Let’s make a place where they can be heard more.

Something about my upbringing - which is gradually becoming clear to me and that I appreciate - is that any artistic pursuit was always about expressing yourself, and never talked about as being anything else

Just thinking about the agonising question. So the answer is, no, I don’t agonise. I’m very clear because I have reasons like that for writing the music, ie, the audience, the band, me, the album that I want to make which is meant to be like that piece of carved wood. It's a finished statement which has a meaning whether or not anybody knows about it. It's an object, like a sculpture in the middle of the Lake District that no one’s going to see, for instance.

Something about my upbringing - which is gradually becoming clear to me and that I appreciate - is that any artistic pursuit was always about expressing yourself, and never talked about as being anything else. Let’s take these days now that we live in as a contrast. If you’re a young person growing up and there’s a lot of television at home, you might think that one of the most important things about being a performer is to get on a big stage in front of some judges and win a competition. And that’s an enormous difference, those are real extremes.

Something about my upbringing - which is gradually becoming clear to me and that I appreciate - is that any artistic pursuit was always about expressing yourself, and never talked about as being anything else. Let’s take these days now that we live in as a contrast. If you’re a young person growing up and there’s a lot of television at home, you might think that one of the most important things about being a performer is to get on a big stage in front of some judges and win a competition. And that’s an enormous difference, those are real extremes.

I had no idea that musicians got paid, probably, for many years. The first book I read about a musician would have been about Charlie Parker (pictured above left) and I read that book and would have been left with the impression of a man who was driven by the possibilities of his instrument first of all, and then had some very difficult life challenges to deal with as well. And the whole thing being a big picture of an artist.

I went to school at a certain age, I guess from about seven till 11 years old. I went to a free school based on Summerhill. And roaming around those years, playing in mud and strumming a guitar, for a while I thought that was possibly a bit of a waste of time. But, actually, looking back I was thinking: God, all that time I was there I just played the blues on the guitar pretty much. I didn’t really develop anything or kind of hone my skills or have much teaching. But then I thought, actually, maybe there is a valuable lesson in there that I’ll understand one day. That you can just strum on one chord all day and if you get into it and other people are enjoying it then it’s not a bad use of the day.The Loose Tubes reissues do make quite a lot of the music around at the moment seem slightly monochromatic. What contemporary music do you really love?

The last thing I remember hearing and being excited and surprised by was a band called The Dirty Projectors (pictured right). They’ve probably been around for a while. New York, arty scene, pop music. I think it’s pop but it’s that kind of pop, like Björk, where it seems that she’s doing absolutely what she wants when she makes an album and I hope that’s true, that’s my belief. Unlike the vast majority of pop people who do sometimes do great things but you always have that feeling that there’s a control filter about what’s allowed out. The Dirty Projectors do some really odd things in the music but not in a prog rock way, in a much more organic, exciting way: lots of voices interlocking in a weird way like pigmy singing, with a guy at the front singing in a very strange voice - a naturally strange voice. And then odd things happening in the rhythm section, a very raw sound, quite a small band. So lots of interesting things about that.

The last thing I remember hearing and being excited and surprised by was a band called The Dirty Projectors (pictured right). They’ve probably been around for a while. New York, arty scene, pop music. I think it’s pop but it’s that kind of pop, like Björk, where it seems that she’s doing absolutely what she wants when she makes an album and I hope that’s true, that’s my belief. Unlike the vast majority of pop people who do sometimes do great things but you always have that feeling that there’s a control filter about what’s allowed out. The Dirty Projectors do some really odd things in the music but not in a prog rock way, in a much more organic, exciting way: lots of voices interlocking in a weird way like pigmy singing, with a guy at the front singing in a very strange voice - a naturally strange voice. And then odd things happening in the rhythm section, a very raw sound, quite a small band. So lots of interesting things about that.

Is there anything in the current jazz scene that excites you?

I’m trying to think. I go to jazz gigs and quite often it’ll be someone that I’ve been watching for 10 years or more who happens to be in town and it's a chance to see them again, rather than this is a brand-new thing I want to check out. The last jazz gig I saw would have been Craig Taborn, Lotte Anker and Gerald Cleaver. That’s like a band, they’ve been together a long time and I knew it was going to be a good gig full of careful development of free material.

I can see how the music irritates some people, but I can’t do anything about that and I’m not going to change the music, because it has to have the elements in it that it has

Going back to the point you made earlier about soaking up all this different music and how it may or may not come out in your own compositions. Do you think it’s that element of nostalgia that some critics have a slight problem with? The sentiment combined with the humour seems to make some critics uneasy.

I think it comes back to something I was saying a while ago about being brought up: that an artistic statement is everything, it's complete. It stands alone, it doesn’t require stilts and props and comments, really. And I know it’s unusual but I never question anything that I do – that’s not right: the questions are for me to ask and for me to answer, so I ask a lot of questions and I answer them. But outside of that I don’t give it much thought. I can see how the music irritates some people, but I can’t do anything about that and I’m not going to change the music, because it has to have the elements in it that it has. I have to accept, and I have accepted, that there are people around who will always think I'm being naughty on purpose and all of that. And I think, beyond accepting it, there’s nothing more to do.

Listen to "Three Architects Called Gabrielle":

I’ve gone through different phases with this. In the Loose Tubes phase I would get really wound up and write to critics and write things about them, lyrics and stuff like that. Then I went through another phase of gradually realising that it didn’t matter. And now I’m in a phase of perhaps thinking that this is Lost Marble 006, I think, and the longer it goes on without being altered in any way by any commentary the stronger it becomes as a statement, to the point where you just really can’t knock it any more.

I’ll give you an example. Jack Massarik has quite a difficult relationship with this band, the trio Belovèd Bird, because of his affinity with Charlie Parker. Sometimes he’s not sure if we’re serious in all of that. We did a gig where Evan Parker (pictured above left) was a guest and it was a gig that Jack Massarik really didn’t like. Sometimes he has liked gigs but this one he didn’t like, so he kind of knocked it from every angle, hated it - really hated it - and then just reserved the last comment for the unquestionable genius of Evan Parker. And I thought, well, at least it ends with that, a positive comment. And so it should. Evan Parker is sixtysomething years old, he’s pursued his line doggedly and not been pushed off track by anything or anybody. And it’s a good reminder, in a way, that there’s a point where people can’t shoot you down, even if they’re hating the gig. They have to accept: God, he’s still here doing it or she’s still doing it, with none of the normal establishment support.

I’ll give you an example. Jack Massarik has quite a difficult relationship with this band, the trio Belovèd Bird, because of his affinity with Charlie Parker. Sometimes he’s not sure if we’re serious in all of that. We did a gig where Evan Parker (pictured above left) was a guest and it was a gig that Jack Massarik really didn’t like. Sometimes he has liked gigs but this one he didn’t like, so he kind of knocked it from every angle, hated it - really hated it - and then just reserved the last comment for the unquestionable genius of Evan Parker. And I thought, well, at least it ends with that, a positive comment. And so it should. Evan Parker is sixtysomething years old, he’s pursued his line doggedly and not been pushed off track by anything or anybody. And it’s a good reminder, in a way, that there’s a point where people can’t shoot you down, even if they’re hating the gig. They have to accept: God, he’s still here doing it or she’s still doing it, with none of the normal establishment support.

I think some people question how you get from this point of the music to this point, and why this point is so far away from that point. It’s too broad to believe that it isn’t over-thought-out in a way, too broad to believe that it’s just an organic statement. Having said that, I really respect some kinds of music which are very minimal. It’s not that I think everyone has to be doing that.Who are you thinking of?

I love playing with my trio, but if I had to say, this is it now, it's just going to be this, I couldn’t do that

Evan Parker, Bill Evans... You know, I sometimes think about Bill Evans having a piano trio and that’s pretty much all he’s known for. OK, he once or twice played with Miles, but there’s a kind of strength you get from that kind of focus as well. I can appreciate it and be impressed by it, but I just have to accept that’s not me to do that. I love playing with my trio, but if I had to say, this is it now, it's just going to be this, I couldn’t do that.

Given that every Eighties band that you’ve ever heard of has come back together: ABC, Spandau Ballet...

...What are the chances of a Loose Tubes reunion in time for the Olympics?

The Olympics are in about two weeks, aren’t they? I don’t think we’ve been invited, it’s not that kind of band – it's not establishment. It’s funny to think that the answer to that question is much more logistic than artistic or personality based. Since Dancing on Frith Street came out I haven’t noticed any promoter calling up and saying, "Hey, I’d like to put on Loose Tubes, are you interested?" That’s the first thing that needs to happen. Someone needs to actually ask the question. Which is quite good in a way: until that question’s asked we don’t even have to try and put the bits and pieces together. If that question ever is asked, various questions come up from that point on, like of the 32 people who played in the band at different points which of them are the band? Which represent the band? Or do you have all 32 on stage for a kind of party vibe?

The next thing would be a person who takes on that responsibility of organising and making artistic decisions. I wouldn’t mind doing the set list, I’m up for that

It couldn’t be done on the same lines, it being a democratic band, it would never happen because there’d be no one saying, “OK, this is the date of the gig,” because you couldn’t even say that. So the next thing would be a person who takes on that responsibility of organising and making artistic decisions. I wouldn’t mind doing the set list, I’m up for that. And then it would take some time to rehearse the band and that’s the thing which I think if a promoter did call they would probably forget that there should be four days of rehearsing beforehand for which people have to be paid if they've got jobs or if they don’t live in London – all of those factors.

That’s not a flat no.

No, no. I can see it as being quite fun, but I can’t imagine the where and why.

Watch a clip of Django Bates performing "This Feels Like the End":

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more New music

Album: Molly Tuttle - So Long Little Miss Sunshine

The US bluegrass queen makes a sally into Swift-tinted pop-country stylings

Album: Molly Tuttle - So Long Little Miss Sunshine

The US bluegrass queen makes a sally into Swift-tinted pop-country stylings

Music Reissues Weekly: Chip Shop Pop - The Sound of Denmark Street 1970-1975

Saint Etienne's Bob Stanley digs into British studio pop from the early Seventies

Music Reissues Weekly: Chip Shop Pop - The Sound of Denmark Street 1970-1975

Saint Etienne's Bob Stanley digs into British studio pop from the early Seventies

Album: Mansur Brown - Rihla

Jazz-prog scifi mind movies and personal discipline provide a... complex experience

Album: Mansur Brown - Rihla

Jazz-prog scifi mind movies and personal discipline provide a... complex experience

Album: Reneé Rapp - Bite Me

Second album from a rising US star is a feast of varied, fruity, forthright pop

Album: Reneé Rapp - Bite Me

Second album from a rising US star is a feast of varied, fruity, forthright pop

Album: Cian Ducrot - Little Dreaming

Second album for the Irish singer aims for mega mainstream, ends up confused

Album: Cian Ducrot - Little Dreaming

Second album for the Irish singer aims for mega mainstream, ends up confused

Album: Bonniesongs - Strangest Feeling

Intriguing blend of the abstract, folkiness, grunge and shoegazing from Sydney

Album: Bonniesongs - Strangest Feeling

Intriguing blend of the abstract, folkiness, grunge and shoegazing from Sydney

Album: Debby Friday - The Starrr of the Queen of Life

Second from Canadian electronic artist and singer offers likeable, varied EDM

Album: Debby Friday - The Starrr of the Queen of Life

Second from Canadian electronic artist and singer offers likeable, varied EDM

Music Reissues Weekly: The Pale Fountains - The Complete Virgin Years

Liverpool-born, auteur-driven Eighties pop which still sounds fresh

Music Reissues Weekly: The Pale Fountains - The Complete Virgin Years

Liverpool-born, auteur-driven Eighties pop which still sounds fresh

Album: Indigo de Souza - Precipice

US singer's fourth ups the pop ante but doesn't sacrifice lyrical substance

Album: Indigo de Souza - Precipice

US singer's fourth ups the pop ante but doesn't sacrifice lyrical substance

Album: Mádé Kuti - Chapter 1: Where Does Happiness Come From?

Lively new album from the third generation of Nigeria's first musical family

Album: Mádé Kuti - Chapter 1: Where Does Happiness Come From?

Lively new album from the third generation of Nigeria's first musical family

The Human League/Marc Almond/Toyah, Brighton Beach review - affable 1980s-themed seaside package

Retro pop extravaganza bolstered by a (mostly) balmy evening

The Human League/Marc Almond/Toyah, Brighton Beach review - affable 1980s-themed seaside package

Retro pop extravaganza bolstered by a (mostly) balmy evening

Album: Alice Cooper - The Revenge of Alice Cooper

The original Alice Cooper band are back to fly the flag for all the weirdos

Album: Alice Cooper - The Revenge of Alice Cooper

The original Alice Cooper band are back to fly the flag for all the weirdos

Add comment