theartsdesk in Paris: The Oldest Film Star of All | reviews, news & interviews

theartsdesk in Paris: The Oldest Film Star of All

theartsdesk in Paris: The Oldest Film Star of All

As it prepares for a facelift, we celebrate the Eiffel Tower's busy career on canvas and celluloid

The news that work is to begin in February on a major renovation of the 122-year-old Eiffel Tower reminds us that no other monument in the world, including the Statue of Liberty, the Houses of Parliament or the Coliseum, conjures up a city with such immediacy, and none with so much romance. According to Roland Barthes, “the Eiffel Tower is nothing but a place to visit.

During the 12 years I lived in Paris, I hardly ever went near the Tower nor was aware of its presence. Occasionally I saw it in the background but there was no point in visiting it unless one was a tourist. I was far more likely to see this urban icon in its multiform manifestations. For most people, seeing the Tower for the first time is both a familiar and an unfamiliar experience, the structure being so instantly recognisable from the extremes of cheap souvenirs to high art. It is impossible for tourists to come to the Eiffel Tower – the original “Iron Lady” - without bringing their cultural baggage with them.

The Tower could almost have been Chagall’s signature – a motif representing his overwhelming love for Paris

For many literary and artistic figures in the first decades of the 20th century, the Tower was a symbol of modernity. However, in the early days, there were a number of dissenting voices among artists. Maupassant called it an “ungracious giant skeleton”, yet ate at its restaurant every day because it was ‘the one place in Paris where you couldn’t see it”. The Paris Opera architect, Charles Garnier, spoke of the “odious shadow of the odious column built up of riveted iron plates”.

Much later, Jean Cocteau, born in the same year as the Tower, marked his fascination with “the beautiful giraffe in lace” in his libretto for the ballet Les Mariés de la tour Eiffel (The Eiffel Tower Wedding Party, 1921), with music by five of Les Six. An irreverent satire of bourgeois values, it extolled what Cocteau called “the spirit of the new”. Blaise Cendras, in his 1913 poem, saw it as an “Ancient God and Modern Beast”, while Raymond Queneau poeticised its “tibia stairways”.

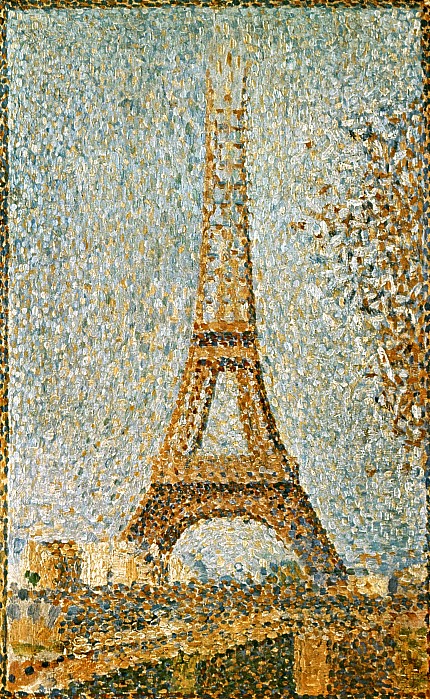

The Tower was painted by Seurat even before it was finished followed in the early part of the new century by Rousseau, Signac, Bonnard, Utrillo, Vuillard and Dufy, all of whom captured the monument in oils, each seeing it through their own individual prisms. The Tower could almost have been Chagall’s signature – a motif representing his overwhelming love for Paris. The Eiffel Tower was the subject of over 30 works by Robert Delaunay in which it was shown from several viewpoints at once, broken into multi-faceted and multicoloured surfaces. The paintings, which suggest the movement of the eye through space and time, are the equivalent of montage in the cinema. Walter Benjamin, in a 1929 essay, called the 12,000 metal fittings and 2.5 million rivets of the Tower “montage in architectural form”.

The Tower was painted by Seurat even before it was finished followed in the early part of the new century by Rousseau, Signac, Bonnard, Utrillo, Vuillard and Dufy, all of whom captured the monument in oils, each seeing it through their own individual prisms. The Tower could almost have been Chagall’s signature – a motif representing his overwhelming love for Paris. The Eiffel Tower was the subject of over 30 works by Robert Delaunay in which it was shown from several viewpoints at once, broken into multi-faceted and multicoloured surfaces. The paintings, which suggest the movement of the eye through space and time, are the equivalent of montage in the cinema. Walter Benjamin, in a 1929 essay, called the 12,000 metal fittings and 2.5 million rivets of the Tower “montage in architectural form”.

Cinema and the Tower made a legitimate couple, both being offsprings of mechanical art and having a relation with riveted architecture - one with its bolts and the other with its splicing. It should be remembered that the Eiffel Tower is only six years older than the cinema, and that the birth and growth of cinema were almost immediately parallel to the birth and growth of modernism in the other arts. It is fitting, therefore, that La Ville-Lumière (of which the Tower is the beacon) should have played host to the first public performance of the Cinématographe on 28 December 1895 at the Salon Indian in the Grand Café in the Boulevard des Capucines presented by the brothers Auguste and Louis Lumière. There is a poetic congruity of their name and profession. Let there be Light! And lo there was Cinema! And the Eiffel Tower was featured almost immediately in the new art. In 1897, the Lumière brothers spotlighted it in Panorama pendant l’ascension de la Tour Eiffel (Panorama Whilst Climbing the Eiffel Tower) while Georges Meliès, filmed the Tower in Images of the 1900 Exhibition.

The Lumière brothers film Paris from on high

René Clair, whose adopted surname means light and bright and whose films have the same reputation for gaiety as Paris, was another movie director to give the Tower a leading role. Paris qui dort (The Crazy Ray, 1925) opens with the young nightwatchman of the Eiffel Tower waking up in the morning and, from his vantage point at the highest point in Paris, discovering that the whole city is at a standstill. On descending (the camera following him dizzily as he runs down the spiral stairway), he finds the streets are filled with stationary cars and motionless people (an effect created with stop-motion photography). They have been victims of a mad doctor who has frozen them with a magic ray. Those people unaffected, having just arrived in Paris by plane, and the watchman, loot the city and go and live in luxury on the Eiffel Tower, which becomes a magical safe place up in the sky. Clair treats the Tower in a Realist, Surrealist and Cubist manner, giving it its first recognition on film as a modernist work of art. Clair also made a vividly composed 14-minute documentary, La Tour (1928), as abstract as it is factual.

Many years later, Louis Malle paid homage to Paris qui dort in Zazie dans le métro (1960): a vertiginous sequence on the Tower uses slow and speeded-up motion. In Charles Crichton’s Ealing comedy, The Lavender Hill Mob (1950), it is used as a setting for a madcap chase down the stairs by two bank robbers (Alec Guinness and Stanley Holloway) who have smuggled the stolen gold bullion into France in the form of Eiffel Tower paperweights. It’s a case of kitsch souvenir Eiffel Towers meeting the real Eiffel Tower.

The Eiffel Tower in Zazie dans le métro

In Hollywood, it was a rare Paris-set movie where the Eiffel Tower was not visible from someone’s hotel room or apartment. (Actually, since restrictions limit the height of most buildings in Paris to 7 stories, only a very few of the taller buildings have a clear view of the tower.) An establishing shot of the Tower (with a few bars of La Marseillaise to labour the point) was all that was needed to explain where the action was taking place. In Hollywood musicals, no Parisian production number, which always had as much oo-la-la as tra-la-la, could do without it, even if Doris Day in April in Paris (1952) sings of the “Awful awful Eiffel Tower!” in the song “That’s What Makes Paris Paree”.

In Stanley Donen’s Funny Face (1957), actually shot on location, Fred Astaire, Audrey Hepburn and Kay Thompson on first arriving in Paris go their different ways seeing the sights and singing “Bonjour Paris”, until all three suddenly realise, “There’s something missing. There’s still one place I’ve got to go.” Naturally, they end up to that “monument to chic” – the Eiffel Tower. Judy Garland in George Cukor’s A Star is Born (1954), using everyday objects around her in the living room, and singing “Somewhere There’s a Someone”, sends up a huge production number in which she is “discovered on top of the Eiffel Tower”.

In Stanley Donen’s Funny Face (1957), actually shot on location, Fred Astaire, Audrey Hepburn and Kay Thompson on first arriving in Paris go their different ways seeing the sights and singing “Bonjour Paris”, until all three suddenly realise, “There’s something missing. There’s still one place I’ve got to go.” Naturally, they end up to that “monument to chic” – the Eiffel Tower. Judy Garland in George Cukor’s A Star is Born (1954), using everyday objects around her in the living room, and singing “Somewhere There’s a Someone”, sends up a huge production number in which she is “discovered on top of the Eiffel Tower”.

Ernst Lubitsch, who directed around a dozen films set in Paris, once remarked, “I’ve been to Paris, France, but Paris Paramount is better.” Lubitsch’s Ninotchka (1939) – actually Paris, MGM – has a scene where stern Russian commissar Nina Ivanoff (Greta Garbo) first meets playboy aristocrat Leon d'Algout (Melvyn Douglas). (See clip below after one minute 50 seconds)

Ninotchka: I’m looking for the Eiffel Tower.

Leon: Good heavens, is that thing lost again?... Oh, are you interested in a view?

Ninotchka: I’m interested in the Eiffel Tower from a technical standpoint.

Leon: Technical? No, no, I’m afraid I couldn’t be of much help from that angle. You see, a Parisian only goes to the tower in moments of despair to jump off.

Ninotchka: How long does it take a man to land?

Soon the Tower becomes the locus of their love affair. Billy Wilder, co-screenwriter on Ninotchka, expressed how Hollywood imitated Lubitsch’s fade in - fade out from a champagne bottle to the Eiffel Tower every time a film had a scene in Paris.

It is rare in films for the Tower to be connected with anything dark or pessimistic. The engineering marvel (the signifier) evoked frivolity, gaiety and sybaritism (the signified). One of the few exceptions is The Man on the Eiffel Tower (1949), a film noir in Technicolor, which has Charles Laughton as Inspector Maigret investigating a murder. The film, which gives the “City of Paris” fifth billing in the credits, has a climactic chase on the Eiffel Tower (pictured), reminiscent of the finale of Alfred Hitchcock’s Saboteur (1942) atop the Statue of Liberty.

It is rare in films for the Tower to be connected with anything dark or pessimistic. The engineering marvel (the signifier) evoked frivolity, gaiety and sybaritism (the signified). One of the few exceptions is The Man on the Eiffel Tower (1949), a film noir in Technicolor, which has Charles Laughton as Inspector Maigret investigating a murder. The film, which gives the “City of Paris” fifth billing in the credits, has a climactic chase on the Eiffel Tower (pictured), reminiscent of the finale of Alfred Hitchcock’s Saboteur (1942) atop the Statue of Liberty.

Sometimes, the absence of the Tower is as noticeable as its presence. There is no way it could make an appearance in the poetic realist Paris of Marcel Carné. When Arletty, standing on a bridge on the Canal St Martin in Hôtel du Nord (1938), cries “Atmosphere! Atmosphere! Est-ce que j’ai une gueule d”atmosphère?” one of the most celebrated lines in French cinema, the Eiffel Tower could be in another city.

The French New Wave directors, who set out to capture the life of early 1960s France, especially Paris as it was lived by its young people, were not afraid to include the Tower in a fresh manner. In 1957, François Truffaut wrote a script for a 25-minute film called Autour de la Tour Eiffel (Around the Eiffel Tower), about persons obsessed with getting to the tower, which they can see easily, but can never reach. In one version, a peasant finally reaches the top and sees “a Parisian Paris down to the fingertips”. The film was never made, but two years later, in the credits for Les quatre cents coups (The 400 Blows), Truffaut’s first feature, the camera scanning the streets of Paris comes to a halt at the foot of the Tower. Truffaut would collect replicas of the Tower in all sizes, which he displayed in his apartment in the 16th arrondisement, from which the Tower itself was visible. (Pictured above, Truffaut filming Baisers Volés in 1968.) In the last scene of Jacques Rivette’s Out One: Spectre (1972), Jean-Pierre Léaud plays obsessively with a tiny Eiffel Tower reproduction, as if to destroy it.

The French New Wave directors, who set out to capture the life of early 1960s France, especially Paris as it was lived by its young people, were not afraid to include the Tower in a fresh manner. In 1957, François Truffaut wrote a script for a 25-minute film called Autour de la Tour Eiffel (Around the Eiffel Tower), about persons obsessed with getting to the tower, which they can see easily, but can never reach. In one version, a peasant finally reaches the top and sees “a Parisian Paris down to the fingertips”. The film was never made, but two years later, in the credits for Les quatre cents coups (The 400 Blows), Truffaut’s first feature, the camera scanning the streets of Paris comes to a halt at the foot of the Tower. Truffaut would collect replicas of the Tower in all sizes, which he displayed in his apartment in the 16th arrondisement, from which the Tower itself was visible. (Pictured above, Truffaut filming Baisers Volés in 1968.) In the last scene of Jacques Rivette’s Out One: Spectre (1972), Jean-Pierre Léaud plays obsessively with a tiny Eiffel Tower reproduction, as if to destroy it.

The Tower, whether seen as phallic or feminine, has been the subject of tower-envy. How else can one explain its wanton destruction in several Hollywood films from The War of the Worlds (1953) to Mars Attacks! (1996) and Armageddon (1998). But it still remains inviolable. There are not many film stars who are still going at the age of 122, a facelift notwithstanding.

- Ronald Bergan’s latest book is The Film Book: A Complete Guide to the World of Cinema (Dorling Kindersley)

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Film

Anemone review - searching for Daniel Day-Lewis

The actor resurfaces in a moody, assured film about a man lost in a wood

Anemone review - searching for Daniel Day-Lewis

The actor resurfaces in a moody, assured film about a man lost in a wood

Train Dreams review - one man's odyssey into the American Century

Clint Bentley creates a mini history of cultural change through the life of a logger in Idaho

Train Dreams review - one man's odyssey into the American Century

Clint Bentley creates a mini history of cultural change through the life of a logger in Idaho

Palestine 36 review - memories of a nation

Director Annemarie Jacir draws timely lessons from a forgotten Arab revolt

Palestine 36 review - memories of a nation

Director Annemarie Jacir draws timely lessons from a forgotten Arab revolt

Relay review - the method man

Riz Ahmed and Lily James soulfully connect in a sly, lean corporate whistleblowing thriller

Relay review - the method man

Riz Ahmed and Lily James soulfully connect in a sly, lean corporate whistleblowing thriller

Die My Love review - good lovin' gone bad

A magnetic Jennifer Lawrence dominates Lynne Ramsay's dark psychological drama

Die My Love review - good lovin' gone bad

A magnetic Jennifer Lawrence dominates Lynne Ramsay's dark psychological drama

Bugonia review - Yorgos Lanthimos on aliens, bees and conspiracy theories

Emma Stone and Jesse Plemons excel in a marvellously deranged black comedy

Bugonia review - Yorgos Lanthimos on aliens, bees and conspiracy theories

Emma Stone and Jesse Plemons excel in a marvellously deranged black comedy

theartsdesk Q&A: director Kelly Reichardt on 'The Mastermind' and reliving the 1970s

The independent filmmaker discusses her intimate heist movie

theartsdesk Q&A: director Kelly Reichardt on 'The Mastermind' and reliving the 1970s

The independent filmmaker discusses her intimate heist movie

Blu-ray: Wendy and Lucy

Down-and-out in rural Oregon: Kelly Reichardt's third feature packs a huge punch

Blu-ray: Wendy and Lucy

Down-and-out in rural Oregon: Kelly Reichardt's third feature packs a huge punch

The Mastermind review - another slim but nourishing slice of Americana from Kelly Reichardt

Josh O'Connor is perfect casting as a cocky middle-class American adrift in the 1970s

The Mastermind review - another slim but nourishing slice of Americana from Kelly Reichardt

Josh O'Connor is perfect casting as a cocky middle-class American adrift in the 1970s

Springsteen: Deliver Me From Nowhere review - the story of the Boss who isn't boss of his own head

A brooding trip on the Bruce Springsteen highway of hard knocks

Springsteen: Deliver Me From Nowhere review - the story of the Boss who isn't boss of his own head

A brooding trip on the Bruce Springsteen highway of hard knocks

The Perfect Neighbor, Netflix review - Florida found-footage documentary is a harrowing watch

Sundance winner chronicles a death that should have been prevented

The Perfect Neighbor, Netflix review - Florida found-footage documentary is a harrowing watch

Sundance winner chronicles a death that should have been prevented

Blu-ray: Le Quai des Brumes

Love twinkles in the gloom of Marcel Carné’s fogbound French poetic realist classic

Blu-ray: Le Quai des Brumes

Love twinkles in the gloom of Marcel Carné’s fogbound French poetic realist classic

Add comment