Sargent and the Sea, Royal Academy | reviews, news & interviews

Sargent and the Sea, Royal Academy

Sargent and the Sea, Royal Academy

The great portraitist honed his craft on sea paintings

There’s a little-known side to the 19th-century American artist John Singer Sargent, and it is as far removed from the razzle-dazzle of his glittering career as a high-society portraitist as you can imagine. The artist who was famously described by Rodin as “the Van Dyck of our times” started his career emulating that great master of the seas, J M W Turner. He diligently honed his craft by painting dramatic seascapes, gentle coastlines and noble fishing folk. And if the 20-year-old Sargent couldn’t quite manage the roiling waves and lowering skies with quite the same level of brilliance as the English painter, he nonetheless possessed a quite remarkable artistic maturity. Turner, by contrast, couldn’t paint a convincing human figure for love nor money.

Born in Florence to Europhile, expat parents, Sargent’s early life seemed to consist of one perpetual grand European tour: France, Germany, Italy, Switzerland, all provided temporary homes for the cultured and quadralingual young artist. But it was the artistic centre of Paris that remained a base. And although his father had hoped for a naval career for his son – a love of ships and the sea, as well as of boisterous adventure, evident from an early age – Sargent remained in Paris to pursue his artistic training. Degas, Monet and Whistler would become artists to emulate, though clearly it was a boyhood passion for the drama of the waves that Turner, Sargent’s first great inspiration, satisfied.

The Royal Academy’s illuminating exhibition begins in 1874, with Sargent aged just 18. It focuses on the five years that he worked diligently on his marine paintings, painting and sketching first on the Normandy and Brittany coasts, then in Capri and various Mediterranean ports. It is the year of the Impressionist’s first exhibition, but Sargent would have known little if anything at all of this avant-garde movement. His own paintings are denser, darker, more polished, in the Salon style, but with touches of the bravura brilliance that would seduce and dazzle in his later portraits.

The Royal Academy’s illuminating exhibition begins in 1874, with Sargent aged just 18. It focuses on the five years that he worked diligently on his marine paintings, painting and sketching first on the Normandy and Brittany coasts, then in Capri and various Mediterranean ports. It is the year of the Impressionist’s first exhibition, but Sargent would have known little if anything at all of this avant-garde movement. His own paintings are denser, darker, more polished, in the Salon style, but with touches of the bravura brilliance that would seduce and dazzle in his later portraits.It would be a full 10 years before his most famous painting, the portrait of that bare shouldered siren Madame X, would scandalise Parisian high society, making a scarlet woman of its subject and persuading Sargent to leave Paris for London for good. (Perhaps, finding that success had come too easily, and not immune to the charges of superficiality that his glamorous portraits excited, he later condemned portraiture as “a pimp’s profession” and returned to his safe and beloved coastal scenes.)

But this was all to come. Here, a sketch of a shipwreck in 1876, shows an exuberant copy of Turner’s 1805 painting of that name, while, in Atlantic Storm, c 1876 (main picture), the vertiginous dip of a steamship’s deck as it makes its way through the high seas, was painted while Sargent was crossing the Atlantic for the first time to visit America. Two shadowy passengers attempt to make their way up the sloping deck - the precocious Sargent always had an eye for narrative drama.

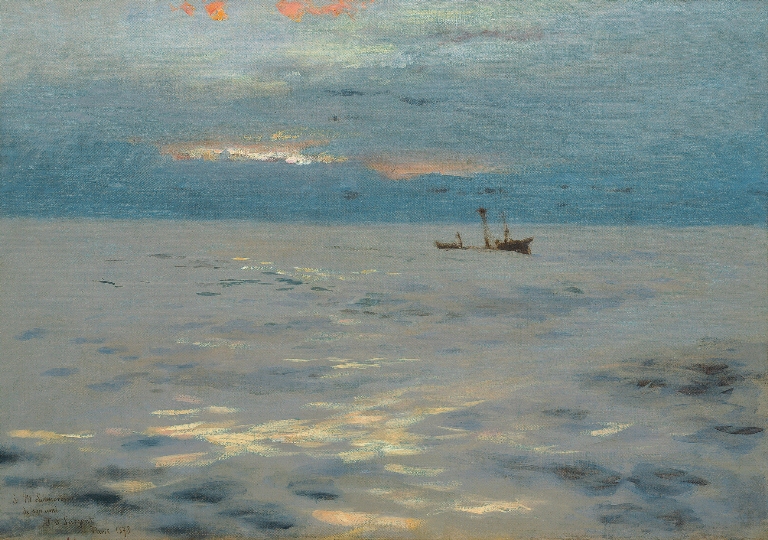

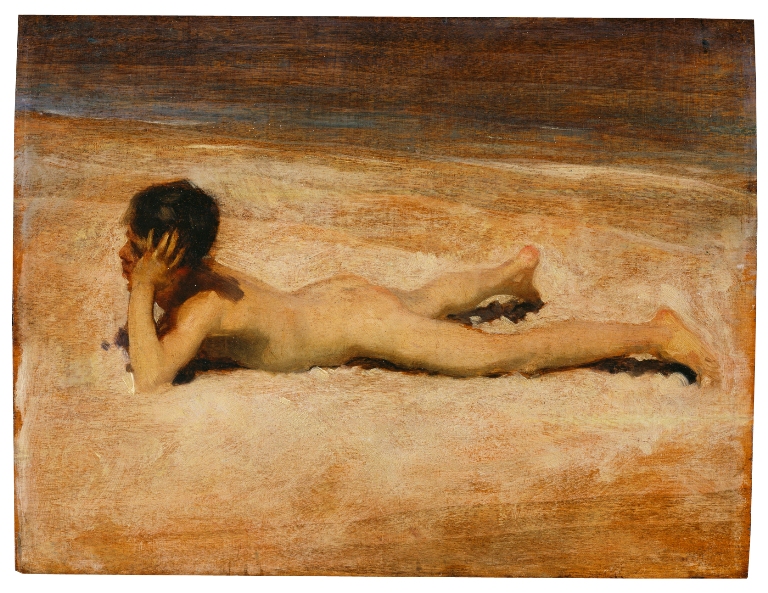

There is, of course, little to scandalise here, though we might easily detect a hint of the homoerotic in Sargent’s Capri paintings of carefree Neapolitan boys bathing nude (pictured left: A Nude Boy on a Beach, 1878). But, apart from those displayed in a few notebook sketches, his first few years show surprisingly little interest in the human figure. Instead we find sketches of marine life: a painting executed in dark brown hues of two glistening octopi, tentacles entwined; tumultuous seas unbounded by land, with a ship tossed by waves viewed at a distance, so that we may be awed by the power of nature (pictured above right: Atlantic Sunset, c 1876); and quiet little harbours with sailing boats all at anchor.

There is, of course, little to scandalise here, though we might easily detect a hint of the homoerotic in Sargent’s Capri paintings of carefree Neapolitan boys bathing nude (pictured left: A Nude Boy on a Beach, 1878). But, apart from those displayed in a few notebook sketches, his first few years show surprisingly little interest in the human figure. Instead we find sketches of marine life: a painting executed in dark brown hues of two glistening octopi, tentacles entwined; tumultuous seas unbounded by land, with a ship tossed by waves viewed at a distance, so that we may be awed by the power of nature (pictured above right: Atlantic Sunset, c 1876); and quiet little harbours with sailing boats all at anchor. What may seem surprising is that Sargent painted the working coast, not the newly popular resorts and fashionable promenades bought to vivid life by the fresh palette of the Impressionists. And, like Millet, Sargent’s ordinary working folk, particularly in his large-scale En Route pour la pêche, 1878 (pictured right), possess an idealised dignity: far from the fleeting impression, he attempts to give a sense of monumentality to ordinary human endeavour. In doing so, his paintings of oyster catchers in Cancale, on the Brittany Coast, are Sargent’s greatest achievement of this period. Knowing just how to arrange these figures in relation to one another, our eyes are drawn in, captivated by the whole. Finally he has focused on the human.

What may seem surprising is that Sargent painted the working coast, not the newly popular resorts and fashionable promenades bought to vivid life by the fresh palette of the Impressionists. And, like Millet, Sargent’s ordinary working folk, particularly in his large-scale En Route pour la pêche, 1878 (pictured right), possess an idealised dignity: far from the fleeting impression, he attempts to give a sense of monumentality to ordinary human endeavour. In doing so, his paintings of oyster catchers in Cancale, on the Brittany Coast, are Sargent’s greatest achievement of this period. Knowing just how to arrange these figures in relation to one another, our eyes are drawn in, captivated by the whole. Finally he has focused on the human.His palette was to brighten, his paintwork to achieve a more impressionistic looseness, but here is where it started. One can catch glimpses of his greatness right here.

- Sargent and the Sea at the Royal Academy until 26 September

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Photo Oxford 2025 review - photography all over the town

At last, a UK festival that takes photography seriously

Photo Oxford 2025 review - photography all over the town

At last, a UK festival that takes photography seriously

![SEX MONEY RACE RELIGION [2016] by Gilbert and George. Installation shot of Gilbert & George 21ST CENTURY PICTURES Hayward Gallery](https://theartsdesk.com/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail/public/mastimages/Gilbert%20%26%20George_%2021ST%20CENTURY%20PICTURES.%20SEX%20MONEY%20RACE%20RELIGION%20%5B2016%5D.%20Photo_%20Mark%20Blower.%20Courtesy%20of%20the%20Gilbert%20%26%20George%20and%20the%20Hayward%20Gallery._0.jpg?itok=7tVsLyR-) Gilbert & George, 21st Century Pictures, Hayward Gallery review - brash, bright and not so beautiful

The couple's coloured photomontages shout louder than ever, causing sensory overload

Gilbert & George, 21st Century Pictures, Hayward Gallery review - brash, bright and not so beautiful

The couple's coloured photomontages shout louder than ever, causing sensory overload

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Comments

Astonishing, breathtaking,