'The first thing I do when I wake up is write ' Hilary Mantel, 1952-2022 | reviews, news & interviews

'The first thing I do when I wake up is write.' Hilary Mantel, 1952-2022

'The first thing I do when I wake up is write.' Hilary Mantel, 1952-2022

An interview with the novelist the morning after she won the Man Booker Prize for the first time

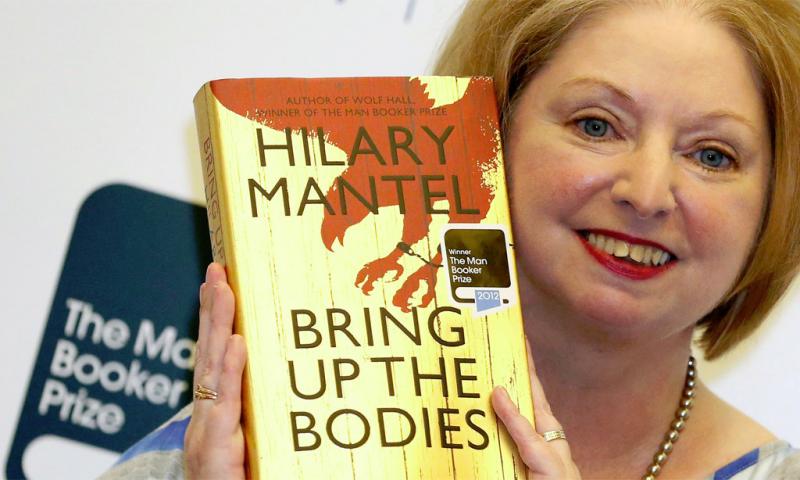

Hilary Mantel, who has died at the age of 70, was a maker of literary history. Wolf Hall, an action-packed 650-page brick of a book about the rise and rise of Thomas Cromwell, won the Man Booker Prize in 2009. Three years later its successor, Bring Up the Bodies, became the first sequel ever to win the prize in its 44-year history.

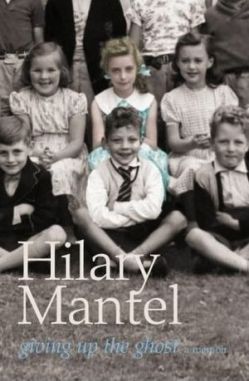

As she movingly described in her memoir, Giving Up the Ghost (2003), Mantel's life involved considerable struggle. Even without her health problems, she had a difficult enough childhood growing up in Derbyshire, whose accent she firmly retained. Her father was more or less ousted from the home when she was 11 and, taking her stepfather’s surname, she never saw him again.

A king who had six wives and cut the heads off two of them? It's outrageous

Mantel went on to suffer years of medical misdiagnosis, including mental illness. She married at 20. Her husband Gerald was a geologist whose job took them to Botswana. There, researching her own symptoms, she duly discovered that she had endometriosis, in which tissue lining the inside of the uterus begins to grow on the outside too. The cost was the loss of her womb and of the chance to have a child – the ghost of the title of her memoir. Steroid treatment encased the ghost of a svelte Mantel inside a larger frame.

Her debut novel, Every Day is Mother's Day, was published in 1985; its sequel, Vacant Possession, came the following year. Eight Months on Ghazzah Street, inspired by a period when her husband's work took them to Saudi Arabia, came out in 1988. A year later Fludd, set partly in a northern English village in the heady religious atmosphere of the 17th century, "bears some but not much resemblance," its author advised, "to the Roman Catholic Church in the real world, c. 1956." It won several awards. A Place of Greater Safety, an ambitious historical novel set in the French Revolution, appeared in 1992. A prolific decade also yielded A Change in Climate (1994), An Experiment in Love (1995) and The Giant, O'Brien (1998). Aside from the memoir and some short stories also provoked by childhood recollections, her only other novel until she embarked on the Wolf Hall trilogy about Cromwell was Beyond Black (2005). She was appointed a CBE in 2006 and a DBE in 2014.

This interview was conducted with Mantel the morning after she won the Booker Prize for the first time. It is reproduced here in full.

JASPER REES: The morning after the night before, one tabloid headline attributed your first Booker victory as if by divine right to the monarchy. "Booker Prize is won by Henry VIII," it said. What did you make of that?

JASPER REES: The morning after the night before, one tabloid headline attributed your first Booker victory as if by divine right to the monarchy. "Booker Prize is won by Henry VIII," it said. What did you make of that?

HILARY MANTEL: He’d have claimed it. That’s the thing about Henry. Wolsey warns Cromwell that he will take credit for all your successes and he will blame you for all your failures. And that is the prerogative of an absolute monarch. It’s a very odd thing because you prepare yourself for failure, so two of you go to the Booker dinner, the one who is going to win and the one who is going to lose. It really is a big thing and I would never try to deny that. I’m not going to play it cool. You know it is going to change your career. It may not change your writing, but your career is a different thing.

Presumably it also changed the future of the expected sequel?

People had been saying to me, “Hurry up.” One lady wrote to me and expressed a wish that the sequel would come along soon and put, “PS I am 94.” It made me feel very responsible. The wonderful thing for me was the warmth of the reception for Wolf Hall even before the Booker shortlisting. Because can you imagine how it would be if you wrote a big novel like this, looking to a sequel, and people were tepid in their reception? It wouldn’t really hearten you to get on with the next book.

To promote the book you used a particular phrase several times. When did you first mint the idea of the Tudor period as “our national soap opera"?

It may not even have originated with me. I couldn’t tell you. It’s a real cliché but you’re under the pressure to get to the point quickly and something like that comes out. But I think it’s true, because I sometimes think we must be the envy of other nations. A king who had six wives and cut the heads off two of them? It’s outrageous. It doesn’t seem like real life. It seems like a novel. And what we have to remember is that Henry didn't know he was going to have six wives. Even when he married number five he didn’t know it. The temptation is to view it from a distance and think it was all predetermined. And it wasn’t. I’m trying to catch people as they’re moving forwards through their lives.

But I think the reason we keep going back and back to this story is because of its archetypal quality. You’ve got his great lecherous brute who won’t accept that he’s aging. He’s always got his eye out for a prettier and younger girl. You’ve got a first wife in Catherine of Aragon, saintly but obstinate; we’ve all known a wife like that. She was a professional wife, that’s what Catherine was, as well as a queen. And that was absolutely how she defined her role and she wasn’t going to give up the status of wife. We’ve all known people who hang on to dead marriages. And Anne Boleyn - who hasn’t known the mistress on the make? And then you have this situation: he marries his mistress, he creates a vacancy. It’s all so recognisable in terms of modern family dynamics, and yet it’s all so much nearer the bone because the stakes are so high.

Wolf Hall is about the dismantling of the Catholic apparatus. Did your own relationship with Catholicism in your youth help you to revel in the telling of this story?

Wolf Hall is about the dismantling of the Catholic apparatus. Did your own relationship with Catholicism in your youth help you to revel in the telling of this story?

I’m a contrary sort of person and I think by my middle childhood I was heartily sick of saints. I was obviously brought up as a Roman Catholic, as you say. I’m not hostile to Catholicism, as some people think. Or not necessarily to the theology, although I haven’t got much time for the modern church. But I think some people have seen the novel as an outrageous attack on the reputation of Thomas More and as a travesty of the facts. But the truth is I have not discovered anything new about More. Every biographer however friendly to him has to include his record as a heresy-hunter. Perhaps what I have done slightly differently is to look at Thomas More from the point of view of the London evangelical community and Thomas Cromwell who is embedded in that community. People have said to me, “He only burned six people.” Only! But it’s not just a matter of that. It’s the martyrs who stick in our head. We may remember their names. But there were other people whose lives he comprehensively wrecked. And maybe it’s this part of the story that perhaps takes people by surprise. What you notice about Thomas More is the glee and relish with which he goes about it.

The idea for a book about Cromwell was 20 years in the making. Could I do some archaeology and dig back to the foundations of the book?

Absolutely. When I started writing I started writing a historical novel. It was what later became A Place of Greater Safety and it was published as my fifth novel. And that was how I saw myself, as a historical novelist. And I think as I moved towards the end of that book – I’m talking about the book in its first incarnation, so I was finishing in 1979 - there was just that thought at the back of my mind: one day I’ll do Thomas Cromwell.

Why?

Well, once you’ve tackled Robespierre and his reputation, Thomas Cromwell seems almost cosy. I had the sense of another era in which the politics would be fascinating and with a fascinating man at the centre of it. In those days my thinking about Cromwell was I suppose fairly orthodox. I had him cast as a villain, but an interesting villain, and I wanted to know what was motivating him. I didn't know a lot about it in those days. All I knew was popular history. And really I was going back to what I’d been taught at school. I was seeing Cromwell as the demon in the Reformation, but it remained at that level for a long time.

And then I suppose about seven years ago, just roughly speaking, I went to Spain to the university at Alcalá outside Madrid – it’s one of those really old 16th-century universities - and one of the academics was taking me around the town and pointed out a grim-looking tower and he said, “That’s where Catherine of Aragon was born.” And my reaction was gratifying: “Wonderful!” And he said, “You know, all the English do that? And to us she’s just a really obscure princess who got married and went abroad. What is all this with the English and Catherine of Aragon?" And I think at that moment it took a move forward in my mind. I thought, yeah, people are still fascinated. It is a story. He said, “What does she mean to you?” And I had to think about it. But I had things to write, I was in the middle of the other projects. And then the time comes. Pictured: Ben Miles and Lydia Leonard in the RSC's Wolf Hall

Pictured: Ben Miles and Lydia Leonard in the RSC's Wolf Hall

Could this project only have happened after you’d written your memoir, Giving Up the Ghost?

I think writing the memoir was a freeing process in some ways. Although I’ve still got a lot of problems with my health, things have improved. And I think the memoir was saying, “Well, that was my past.” And hanging on to the hope that things would be better. You see, I think what a book like this needs is a huge amount of energy, and physical and mental energy feed off one another. And I don’t think I could have done it when I was really ill. The writing of Beyond Black, my last novel, took me a long time. I had a gruelling few years and it held the book back. And then we began to climb up the other side, and I thought that I probably did have the energy to tackle it. It’s all about your internal economy, in a way. How much can you afford to spend?

Is winning good for your health?

It’s good for my spirits and so I think it must be. Having said that, of course it means fairly gruelling schedules, but it’s surprising what will-power will do to keep you going. And really my work has kept me going over the years. It would have been easy to slide into doing nothing very much. But I think if you’ve got a driving idea and an ambition it really tugs you along in its wake. Sometimes I’ve lost confidence because I thought my health was letting me down and I wouldn’t be able to do what I’d promised. And I hate that thought. It’s virtually never happened, but you always fear it. But I think of course the Booker gives you a huge injection of confidence over every area of your life.

You deal in Giving Up the Ghost with a certain amount of psychological cruelty that occurred in your childhood and was associated with your uncertain health. I was wondering if, in that early scene in Wolf Hall in which the boy Cromwell is beaten up by his thuggish father, whether there is any hint of being nicknamed “Never Well”? (Pictured, jacket with Mantel in the centre)

You deal in Giving Up the Ghost with a certain amount of psychological cruelty that occurred in your childhood and was associated with your uncertain health. I was wondering if, in that early scene in Wolf Hall in which the boy Cromwell is beaten up by his thuggish father, whether there is any hint of being nicknamed “Never Well”? (Pictured, jacket with Mantel in the centre)

It was our family doctor who called me that. This has not happened to me. But I know about oppression. I know about oppression within the family, and you just scale it up to the wider political picture. But doesn’t every child, you know? I remember, by the time I was six, wondering why we were working in a classroom from two different blackboards, one with hard sums and one with easy sums. And all the children with holes in their jerseys were on the side with the easy sums. They had been written off already. And when you notice something like that in childhood, they drive through your life. You’ve always got an eye out for underdogs. I was on the side of the hard sums.

I was what you’d call a textbook case. But I had to just find the textbook

There has always been the seam running through your work of the supernatural, the evanescent presence of ghostly spirits. Has this laid another ghost to rest, this empowering new event in your life?

I hadn’t thought of it in that way. No, you see I’m involved in a huge project which includes the second book. In my mind it’s all one big project. So when I get to the end of that, that’s when I can say I’ve achieved something in my writing life. The Booker, wonderful though it is, is a career-marker. It doesn’t change, I think, what you’re going to write.

Can you not say you’ve achieved something thus far?

I really believe that there’s absolutely no room for complacency in a writer’s life. If you looked back and thought that what you’ve done is in some way good enough, you’d stop. You’re always trying to push on and achieve the next thing, see how far you can push a certain line, a certain technique. It’s new every day. I really believe that. And of course you have those days when you wake up thinking, maybe I can’t do it any more, maybe it’s gone.

How often does that happen?

Well, I keep my notebook by my bed and the first thing I do when I wake up is write. I make sure. There are odd days when I can’t do it. It’s very important to me because I think there is an inbuilt resistance to writing. The thing is, break it before you’re really awake, and then you can say, "Today I have written." It doesn’t matter what nonsense it is. So it isn’t so hard to do the next bit.

Is the dogged researcher in you the same person who, while living in Botswana, managed to diagnose herself?

Exactly the same person, I think. I like to get a grasp of a new subject, to wade in, grab everything there is to be read, get some sense of it. The only problem is, working as a literary critic and a journalist, you immerse yourself in something and then a couple of months later you’ve forgotten everything about it, you’ve moved on. There is a kind of objectivity about the process which does appeal to me. And you’re right, I was able to treat myself as a case.

Was there a "eureka" moment when you diagnosed yourself and thought, that’s it?

Yes, more or less. I was what you’d call a textbook case. But I had to just find the textbook. Nevertheless when I came back to England the doctors didn’t necessarily agree with me. I didn’t actually know until I was in surgery. Well, until I woke up from surgery. So it didn't do me any good, diagnosing myself. It didn't speed things up. It just made doctors think I was arrogant.

How long did it take for them to do the operation after your self-diagnosis?

I finished my final draft of A Place of Greater Safety, as I thought of it then, towards the end of 1979. We were due home leave after almost three years. We’d been in Botswana for almost three years. I did my final pages. My health then collapsed totally. And it wasn’t accidental. The book was keeping me going. I think - perhaps this sounds melodramatic – but obviously there was a part of me that thought I might have cancer, as indeed the doctors did. Or some of the doctors. I thought, if I’m going to die I’m going to leave this book behind. So it kept me going until the book was finished. We were then due for leave and I’d had all sorts of plans as to how to spend that leave. But I came back and I spent Christmas in hospital. It was just then a matter of a few weeks after getting back to Britain.

If you’d been living in Tudor times...

I’d have been probably dead by the time I was 27. That would have killed me off if nothing else had got to me first.

Are you still very much a child of Derbyshire and the world you grew up in?

A lot of important things seemed to happen in my life before I was four, so to that extent, yes. All those years up to 11 when I lived in Derbyshire are still very vivid in my mind. When I was 11 we moved over the county boundary to Cheshire. It was a completely different world. And then I moved away to university at 18. I don’t really seem to come from anywhere now. I am a northerner, obviously. But - can I say? - after those years abroad, almost 10 years abroad in total, we’ve lived in the South-East since the mid-Eighties. It’s partly a function of my husband’s job.

You have said in a memorable phrase I read in an interview that in terms of your health problems it "feels like being chained to a saboteur". Did that phrase spring up unbidden or has it always run through your head?

You have said in a memorable phrase I read in an interview that in terms of your health problems it "feels like being chained to a saboteur". Did that phrase spring up unbidden or has it always run through your head?

Well, it’s interesting. Obviously it was the way I was feeling that day. But of course I have to wonder if it hadn’t been for my poor health, would I have become a writer at all? Probably not, you see... I think I’d choose the health.

It usually happens that a Booker winner’s backlist springs into fresh bloom. Which of your novels would you wish to have a life of ruder health than they might have in the past?

I think my novel The Giant, O'Brien, which I think came out in 1998, I’m not entirely sure. It came into the world very quietly did The Giant. It had an excellent press, but didn’t win any awards. I had hopes, I suppose, of the Booker shortlist that year because I thought that it was the best thing I’d done to date, and it will always remain singular in my mind because of the manner in which it was written. It was a historical novel that couldn't be more different from this one. And it is special to me because I think when I was writing that novel I sensed a well of power that I hadn’t... a spring of something that I hadn’t begun to tap. And it was a fairly compacted process, I suppose, writing that novel, in that I did get stuck halfway through but apart from that it was one of those books like taking dictation. And although a historical novel, it wasn’t a heavyweight research project. So you were not putting the facts first, not by any means, with that book.

When I began writing I don’t think a lot of male critics actually read women’s novels. They talked about them more than they read them

And what about your novel set in Saudi? You were thinking about our relationship with Islam a long time before everyone else was encouraged to think about it by the events of 9/11.

Yes, absolutely. I was so far ahead that hardly anyone grasped the political dimension of the novel. I felt a bit frustrated, really, because as events developed I had a sort of “I told you so” feeling. You know, you couldn't be in the Kingdom without being conscious of a reservoir of fundamentalism and that you were on the edge of a precipice. But I think Eight Months on Ghazzah Street was my third novel and people concentrated on the gothic elements of it rather than the warning that was in there.

You have in the past had to suffer the suggestion put about by predominantly male critics not only to yourself but also other female novelists that your work was essentially domestic, that you wrote, in that belittling phrase, domestic novels. Is winning the Booker Prize an elegant and gratifying riposte?

Well, A Place of Greater Safety was my first-written book. If that is not a political novel, if the French Revolution is not a political subject, what is? I think actually when I began writing I don’t think a lot of male critics actually read women’s novels. They made an assumption as to what was between those covers, they talked about them more than they read them, and you could write something very explicitly political like Eight Months on Ghazzah Street without that side of it being picked up on at all. They thought you shouldn't trouble your little head with it. But there is a way in which as a woman in Saudi Arabia you are invisible. And what can be a better condition than that for an observer?

Is there an opportunity now that you’re so much in the public eye to say to those doctors who thought you were mentally ill, “See how wrong you were”?

Well, I never had to say that because I didn’t buy into it. It was just crass, really. So it’s not something that troubles me except on a personal level. But again it just makes me keenly aware of how easily people can be rendered powerless and how once an assumption is made about a person then everything they do is invalid. So that if someone has decided that you’re mentally ill, if you go on insisting you’re physically ill then that is seen as an aspect of your mental illness. And you’re in a no-win situation. It’s so easy to get into that bind. It’s something I’m very conscious of.

What was the impetus behind The Giant, O’Brien?

I got into midlife and I suddenly remembered I was Irish. And it was the sense of a lost language. I thought, I’ll teach myself Irish. I didn't of course. I just went out and bought the books and the tapes. It’s a very powerful feeling, isn’t it? You suddenly remember, this is where I came from and they spoke a different language. That was why I care so much about the book. To me, I grew up surrounded by Irish relatives and by the time I was 10 they were mostly dead and I just lost that sense of being Irish. And then it just came back, and then the book sang out.

Was that on your mother’s side or your father’s?

My mother’s side, but my father was Manchester Catholic so I assume they were Irish as well. I never really knew my real father’s family.

I read that your real father did see you on the television when you were a Booker judge in 1990. He has since died but you do have a relative by him.

She’s not actually my half-sister. My father married again and he became stepfather to a large family. She’s one of six. She’s my age.

Do you still have contact?

Yes. She wrote to me out of the blue, rather hesitantly making the link. Because I hadn’t said much publicly about my father. But of course that was a strange day. I was going up to Radio 4 to do an interview about my memoir, and people said, “You’ve not heard about your father for all these years.” And I was able to say, “Till this morning,” because I had the letter in my bag.

Are you in contact on a regular basis?

In a way it doesn’t need to be so regular now. We’re friends. We check in on each other. But essentially the business was done up front in our first meeting. She gave me a few things of my father’s. We did quite a lot of letter-writing before we met and she filled me in on the background, although when my father came into her family she was going off to university so he wasn’t in any sense a father to her.

Did you always know that this was going to be more than one book?

No I didn't. I’ve actually been working on it for about five years. Not until I was part way through when I realised that the Thomas More and Thomas Cromwell story needed to be played out for its full dramatic value. And I didn’t see that until I was approaching it. And also I was realising that I was going to put a huge strain of the readers’ time and attention if I pushed on past that point, and also I would lose the dramatic shape. So it’s one of those things: the moment you thought of it, it was completely obvious.

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

Comments

...

Mantel has beautifully