theartsdesk Q&A: Musician Jimmy Cliff | reviews, news & interviews

theartsdesk Q&A: Musician Jimmy Cliff

theartsdesk Q&A: Musician Jimmy Cliff

One of reggae's breakout stars speaks on everything from Peter O'Toole to bongo drums

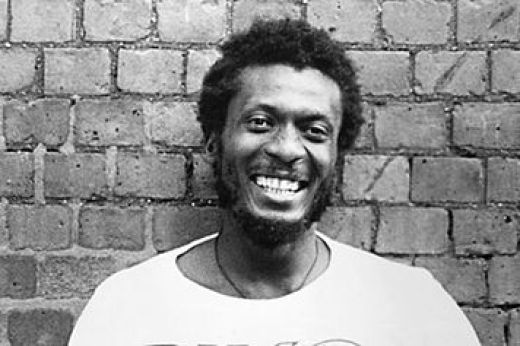

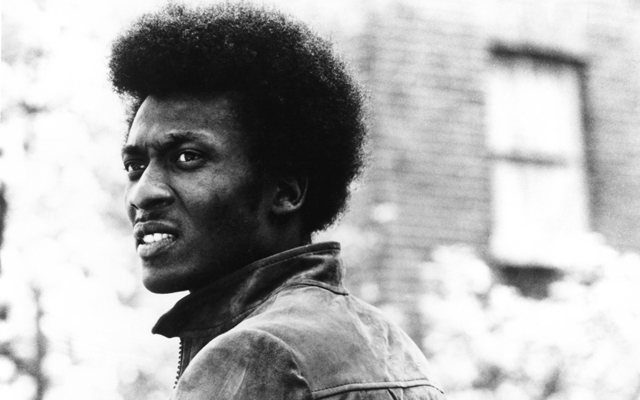

Jimmy Cliff (b 1948) is one of Jamaican music’s biggest names. Raised in the countryside, he went to Kingston in his teens and persuaded record shop owner Leslie Kong to record him.

In 1972 Cliff played the lead role in the film The Harder They Come, about a Jamaican musician who turns to crime, and composed much of its classic soundtrack. Songs from it such as “You Can Get It If You Really Want” and “Many Rivers to Cross” would go on to become among reggae’s most renowned. Cliff was now an international star, a peer of Bob Marley, and toured extensively, building huge fanbases in Africa and South America. Throughout the Seventies, after leaving Island, he produced a series of albums that stylistically pushed reggae’s boundaries before returning to his roots with 1981’s Give the People What They Want. He was heavily involved with Steve Van Zandt’s Artists Against Apartheid in the Eighties and has worked with a wide range of artists including the Rolling Stones and Elvis Costello.

He currently has a new album, Rebirth, his first in eight years, and is touring some of the summer’s festivals, including Camp Bestival next weekend. I meet him in a central-London hotel on a Sunday lunchtime. Casual of dress, svelte of figure, smiley of face and shaven of pate beneath a cap he continually toys with, he sits down in a booth in the bar area with a coffee (or possibly hot chocolate), and answers my questions in a keen, gentle voice tinged with a West Indian lilt.

He currently has a new album, Rebirth, his first in eight years, and is touring some of the summer’s festivals, including Camp Bestival next weekend. I meet him in a central-London hotel on a Sunday lunchtime. Casual of dress, svelte of figure, smiley of face and shaven of pate beneath a cap he continually toys with, he sits down in a booth in the bar area with a coffee (or possibly hot chocolate), and answers my questions in a keen, gentle voice tinged with a West Indian lilt.

THOMAS H GREEN: Have you seen Julien Temple’s film about Joe Strummer, The Future is Unwritten?

JIMMY CLIFF: Actually I’ve not but that’s one I want to see. I’ve been too busy.

The reason I ask is because he was a friend of yours. Was he an influential figure in your life?

I wouldn’t say influential, more inspiring. We have a sameness of mind. When we used to meet we never had time to sit and talk, until the last time, doing “Over the Border” on my last album [Black Magic]. We had time to talk for two weeks. I liked his mind, very bright he was. I miss him.

Listen to Jimmy Cliff and Joe Strummer's "Over the Border"

And on your new album you cover The Clash song "Guns of Brixton", a great song. What do you reckon to the affiliation between punk and Jamaican music?

Punk addresses the political and social issues in the same way. Of course musically the punks adapted something from reggae and put it with rock and came to a unique music style. To be a punk you’re against the system and we were like that in reggae so there was a kinship there.

You cover the Joe Higgs song “World is Upside Down” on your new album too. Tell us about him.

He was a very important character in the reggae business. I knew him before this but a notable thing was he taught Bob and the Wailers harmony. Joe Higgs loved to be of service. His head was full of knowledge but he didn’t write a lot of songs. The few he wrote are so profound. He had another song called “Songs my Enemies Sing”. He was an amazing figure. He didn’t have dreadlocks but he was a true rasta.

You updated the lyrics, singing lines such as “so much war and poverty whilst you enjoy prosperity”.

Joe Higgs’s take was maybe not as universal as mine but he meant the same thing. Joe understood a lot about the church and state psychology, which is global. Where communism rejects the religious side of things - he said if they reject that, they’re a religion themselves, so Joe understood the political system of the world. I’m glad you asked me about him because he’s one of the unsung heroes.

You’ve worked with so many, such as Dean Fraser, the saxophonist – talking of whom, would you say the jazz abilities of Jamaican musicians have been unfairly overshadowed?

You’ve worked with so many, such as Dean Fraser, the saxophonist – talking of whom, would you say the jazz abilities of Jamaican musicians have been unfairly overshadowed?

Go back - at beginning of ska, of reggae, all those musicians were jazz musicians. We came in with maybe an idea about the song and they would frame it for us. I had in mind a long time ago to write a book called The True Story of Reggae because of all these unsung heroes. People need to know about them because they see the light bulb shining but they don’t see the transformer, to know where the power is. Jamaican jazz is really underappreciated – Dean Fraser, Roland Alphonso, Tommy McCook, Lester Sterling, Headley Bennett, [Stanley] Ribbs, all great sax players. Of musicians generally, Ernest Ranglin was voted the number two guitarist in the world at one time. He used to come over here and play jazz at Ronnie Scott’s. I would go as far as to say that, as a guitarist, Ernest Ranglin could give George Benson a run.

You worked with the troubled but brilliant bassist Jaco Pastorius a couple of years before his death in 1987. How did you find him?

Sometimes people are really brilliant - you can call it troubled, but he was brilliant. He came into the studio and he liked me, he give me a big hug, then he wanted to show me who he was. He put his bass down on the ground and he started to jump around it and the bass started playing something. People think he’s crazy but something came out of that bass.

As I understood it, by that stage in his life he was pole-axed by a combination of mental illness, booze and drugs.

He certainly did have problems, but maybe the music kept him alive.

What’s your earliest memory?

In the mountains as a baby, three years old, eating what we call wet sugar, the sugar made from the cane where the mule turns it to get out the juice, they’d turn that to wet sugar. This lady who used to sell it in a big tin would say, “Come here, boy, sing like your mother, laugh like your mother,” and she’d take some sugar and give it to me.

What did your parents do?

My parents were farmers. My father was also a tailor and my mother was a great cook, but most of my family were farmers, whether ground provisions or sugar cane, also cattle, cows, goats. I had to participate in that world but I hated it. I was like the odd man out because when it comes to that I’d go and hide somewhere. “Where is James? I can’t find him.”

Was the producer and entrepreneur Leslie Kong, later one of the original investors in Island Records, a key figure in your rise to Jamaican teen stardom?

Definitely, because when I came to Kingston from the country - I was 15, turning 16 - I tried all the big producers, Sir Coxsone [Dodd), Duke Reid, and they turned me down for whatever reason - “Your voice is too high,” “We don’t like the song.” This one night I became really frustrated and was walking along Orange Street and I saw a sign marked Beverleys Record Store and Ice Cream Parlour [the shop owned by Kong]. In my mind I had this idea for a song called “Beverleys” and in ten minutes I finished the song. I went to the door and they were closing but I pushed my way in and said, “I have a song.” They said, “We’re not in the music business.” “But you could be,” I replied, so I sang the song, “Dearest Beverely”. Kong came into the music business from there, the first Chinese Jamaican to go into the recording business in Jamaica. Then he became “King” Kong of the music business. He was really a great person, he didn’t have great rhythm but he knew sound and had brilliant ideas. He’s missed – he died young of heart problems.

Do you think success as a teenager was good for your psyche and spirituality?

I think so because it was the yearning of my soul, I came here for this. In school I was fairly good at academics, if you challenge me I would show you I could do it, but I really had no interest. When it came to anything with the arts my eyes lit up. To have success at that age kept me alive - literally - because when I went to Kingston I lived in really rough areas and saw violence I never saw in my village. I could have become part of that if it hadn’t been for music.

What was your favourite early hit?

What was your favourite early hit?

One of the early influences was Prince Buster and one of his songs I liked was “The Ten Commandments of Man” – “thou shall not search my pockets at night” - it was hilarious and so profound.

As I understand it, before Bob Marley he was the biggest star in Jamaica.

He had such a stature. He really taught us, myself, Bob Marley, how to think as a businessman and be an artist. He was the first one to own his own record shop, do his own production.

When I asked the question about early hits, I really meant of your own teenage songs.

Of my own music from the Sixties time, “King of Kings” and “One Eyed Jacks”. “One Eyed Jacks” was a song about someone saying you’re a flash in the pan, you’ve got your one little hit with “Hurricane Hattie” and you can’t come back again. I made a song saying, “I know what you’re thinking, silly boy, that I’m only here for a while. Say what you mean, think what you feel, but I live and live and live and never die [sic].” It was a big hit.

Listen to "One Eyed Jacks"

What was it like going to World Fair in New York in 1964 and performing?

Something new for me, my first time in New York City. I’d never seen high buildings like that and I kept looking up and the buildings would never stop. I was just so happy to be performing, I didn’t know what it meant but it was like unexpected dreams coming true. That’s what it was. Then the next day to see the reviews - there was a music mag called Cashbox and they gave me some really big reviews.

Did you find early-Sixties America a place of racial tension?

In New York City I didn’t experience that. The only thing was I stayed at a hotel and the doormen became quite friendly to me. He started telling me a bit about himself – “I have a Cadillac but I can’t tell them because they’ll fire me.” “Why?” “Because I’m a black man, I’m not supposed to have a Cadillac.”

You’ve travelled broadly. You’ve spent quite a bit of time in Africa. What do you take from places like Ghana and Sierra Leone?

My first trip to Africa was Nigeria. It was a bitter-sweet experience. Sweet because of the thousands of people at the airport awaiting me. I’d never had that adulation, I only saw it for The Beatles, so to have it for myself was really great. They lined the street from the airport to the hotel. It was amazing. The bitter part of it was I got thrown in jail for no reason at all. A man came and said, “I’m the one who was supposed to bring Jimmy Cliff to Africa. I had a contract with him in London and he didn’t turn up so now he’s here I’m taking out a civil suit against him.” They put me in jail for three nights. When I went to court, where’s the evidence? Nothing! So they threw it out. Nigeria was a pretty rough place but I didn’t mind - I liked the energy.

Rougher than Sierra Leone?

Sierra Leone was great at that time [in the Seventies]. I enjoyed Sierra Leone. I wasn’t into religion then, I was still Christian-minded. I met all these Muslims telling me different things. I enjoyed Mali too, people sleeping on the street, not because of something bad but because it was so hot. They welcomed me so well, they brought out the national dance troupe, so colourful those dances - I’d never seen anything like that in my life. It blew my mind.

How did you first hook up with Perry Henzell, director of The Harder They Come?

I was in a recording session at [Kingston studio] Dynamic Sounds and when I came out of the session I met this white, bearded Jamaican. He introduced himself and said, “I have a movie, do you think you could write the music?" “What do you mean do I think I can write the music? I can do anything.” Next thing I knew the script came through Island Records over here. Well, they wanted me to play the main part. I read the script, he came to my flat and ran the scene where the grandmother dies and [the main character] comes to see his mother in Kingston. He said,”Wow! You are the man I’ve been looking for all these years.”

Watch the video for "The Harder They Come"

He says he wanted to make a trilogy.

He has said he wanted to, but during the making of that movie I said, “Why does my character have to die?” He said, “Well, you know, crime doesn’t pay and we want to show that.” “So Mr Hilton who robbed me in the film, why doesn’t he die?” At that time I thought I should make a sequel but he wasn’t thinking about a trilogy at that time.

Ivanhoe Martin, the criminal who the central character is based on, is a kind of Ned Kelly figure in Jamaican culture, isn’t he?

Ivanhoe Martin, the criminal who the central character is based on, is a kind of Ned Kelly figure in Jamaican culture, isn’t he?

I knew about him as a child. He struck terror in the minds of people, the name Rhyging [Martin’s patois nickname], because at that time in Jamaica to have a gun and to shoot the police was, like, wow! So Rhyging really means somebody really bad, a bad man, not glamorous, a fearful boogieman. The musical part of the movie Perry added - he extracted that from my life in the music business.

Your new album is produced by Tim Armstrong of the American punk group Rancid.

I was introduced to Tim’s music by Joe Strummer. I covered one of their songs, “Ruby Soho”, on the new album. That completed something for me – “Guns of Brixton” on this side of the Atlantic, “Ruby Soho” on that side.

Why did you say to Rolling Stone magazine, “I’m not done at all. I want to become a stadium act”?

I really have big ambitions. I really intend to win an Oscar because my first love was acting. At school that’s what lifted me up more than anything else. I’m an actor now but to win the Oscar has always been my goal. To have a string of number one hits all over the world would give me the status of playing stadiums. I play stadiums in Africa and South America for Jimmy Cliff shows, I don’t do it worldwide.

Talking of acting, you worked with Peter O’Toole and Robin Williams on the 1986 comedy film Club Paradise. What was that like?

I was surprised Peter O'Toole was such a friendly man. He drank a lot but was civilised with it. He would come in my trailer, having a smoke, having a drink. For me he was a brilliant intellectual, I was in awe of him, to see him come and talk to me. I don’t know if he knew my name. I loved watching him. If he did a scene 12 times, he did it the same way. I learnt a lot from that, as opposed to Robin Williams who, if he was doing a scene 12 times, he did it 12 different ways.

The Sandinistas used your song “You Can Get It If You Really Want” back in 1990 to advertise themselves. Did you approve?

I came to the conclusion that music is like the air we breathe, like oxygen. Even though you can stop people using it by saying I don’t allow that, at the same time it’s still an oxygen. I’m neither here nor there with being proud. In just the same way the British Tory party used it.

That’s not so good.

[Laughs profusely.] The right wing, the left wing - two sides of same thing.

When the Tories used it in 2007 it offended me because of my own perceptions of where you and the song are coming from.

Completely, completely. How can they pick a song like that which has a deep spiritual meaning?

Weren’t you tempted to stop them?

Nope. I came to the conclusion I understood the meaning of politics. “Poli” is people and “tics” are blood-sucking parasites, so they prey on the people.

That sort of talk and word-play sounds like Peter Tosh. Did you know him?

I knew him quite well.

He appeared to be a somewhat edgy individual.

He was but if he opened his door and let you into his world he was the most gentle, caring character you could find. On the outside, on the crust, he was hard, he didn’t let many people into his world. I knew Bob [Marley] but I didn’t know Peter Tosh that well. I grew to know him.

Watch "You Can Get It If You Really Want" on Later... with Jools Holland

Keith Richards spent a lot of time in Jamaica in the Seventies. Was that how you got to know him?

I never spent time with him there. The times we met were more in New York or over here.

How did you end up doing vocals on the Stones album Dirty Work?

Because I’d met Keith and he’d covered “The Harder They Come”. They told me they were doing a session and would I like to come over. I went to experience what a Rolling Stones session was like. It was not exactly like a Jimmy Cliff session. Most of the time I go in with my song ready and play it to the musicians, they pick it up and we do it. That particular Rolling Stones session they had a few other people there, [Fifties rock’n’roller] Don Covay was there and another famous R&B musican. They were lazing around having a smoke and whatnot. If you come up with an idea, the tape is always running, that’s how it was going. Keith was a friendly person. He made me feel at home. Mick is a little different, friendly but very kind of strict, watching and listening and everything not relaxed. You have to keep your distance with Mick.

What are your thoughts about the Mayan calendar predictions about the end of the world in December this year?

What are your thoughts about the Mayan calendar predictions about the end of the world in December this year?

I’m glad you asked me that question. I am someone who studies antiquity, ancient history, ancient civilisations, and I’m very much interested in this. If I didn’t get the gift of music I’d probably like to be an anthropologist. The ancient Egyptians had this knowledge of the change and return of things in our the universe, in our galaxy, and they passed this onto the Babylonians, the Hindus, the Tibetans and the Mayans. They had the Dendera zodiac so they passed all that knowledge onto these other civilisations.

It is a fact that every 2,300 years or so a change comes but beyond that there’s another equinox which is every 24,000 years. That period of 24,000 years is four cycles of 6,000 years and we are at the end of the last 6,000. You have one sun cycle, one moon cycle, one sun cycle, one moon cycle. We’re at the end of the last moon cycle, coming back into the sun, just out of Pisces age and going into the Aquarian age. This is the knowledge that the Mayans had. In this year 2012 we’ll be coming into the new time, it’ll kick right in, the effects of it are already here since the year 2000. When we look at what’s happening politically, economically, spiritually, the idea of religion is becoming obsolete because people are waking up and saying, “Wow! It’s a fictional thing, there’s nothing real about religion,” so all of these laws and systems are no more, we’re coming into new times. In December 2012 they’ll kick right in so, yes, Mayans did have a right knowledge. It’s a change of energy and it happened before on the planet. We are in Armageddon now but it doesn’t mean cataclysmic end times - people will be clearer about how they individually and collectively fit into the universe.

How do you feel about bongo drums?

I love bongo drums. They’re played with the hands so it’s a live energy. The skins of bongo drums are from live animals, not plastic, and the wood is live so you have that trinity, it’s a live thing. It's the only instrument besides the human voice that can penetrate the human body. It’s also a bridge between heaven and earth, like the human voice.

If you could arm wrestle anybody in the world, who would it be?

It depends if I’m doing it for fun. If I’m doing it for fun, I don’t know how good he is now but the person I would have liked to arm wrestle would be Muhammad Ali. I don’t believe I could beat him but just to know I could arm wrestle him would be good. I love boxing. I used to box a little but I got a tough one on the chin and that taught me it’s better I stick with singing.

What’s your favourite smell?

I think it’d have to be amber.

On your Black Magic album you dabbled in electronic music, which was a little unexpected.

On your Black Magic album you dabbled in electronic music, which was a little unexpected.

You know, even when I was doing reggae I was always adding something different. When I did “Wonderful World Beautiful People” it was a great song as it was, but then I added strings to it and it sounded different. Some of my other albums, I made tracks in Jamaica, took them to America and added electronic stuff. I like to be a little different, it’s just another part of my creative outlet. I’ve been criticised for it but I can’t help doing it - that’s who I am. At one time I was going to make an album and call it “Thumb” because I always feel like I’m the thumb, so far from everybody else but I’m on the same hand and if you want to make a firm fist or write you need a thumb.

Are you a religious man?

Religious? No. I used to be. Let’s put it that way. I grew up being religious but when I look in hindsight I was never really religious, I was more spiritual, trying to understand who I am as opposed to what I am. Religion is something you take on or accept in your life and that makes you what you are, not who you are. Who I am has nothing to do with religion. I’ve come to understand all my search through the different strands of organised religion was just my search to understand who I am. I have come to realise it’s not to be found in religion. I found my ancestral roots, my celestial roots, and all of that’s more important to me right now. Everything else can hang from that.

Jimmy Cliff and Tim Armstrong talk about the new album, Rebirth

Explore topics

Share this article

Add comment

more New music

Album: Mdou Moctar - Funeral for Justice

Tuareg rockers are on fiery form

Album: Mdou Moctar - Funeral for Justice

Tuareg rockers are on fiery form

Album: Fred Hersch - Silent, Listening

A 'nocturnal' album - or is it just plain dark?

Album: Fred Hersch - Silent, Listening

A 'nocturnal' album - or is it just plain dark?

Music Reissues Weekly: Linda Smith - I So Liked Spring, Nothing Else Matters

The reappearance of two obscure - and great - albums by the American musical auteur

Music Reissues Weekly: Linda Smith - I So Liked Spring, Nothing Else Matters

The reappearance of two obscure - and great - albums by the American musical auteur

The Songs of Joni Mitchell, Roundhouse review - fans (old and new) toast to an icon of our age

A stellar line up of artists reimagine some of Mitchell’s most magnificent works

The Songs of Joni Mitchell, Roundhouse review - fans (old and new) toast to an icon of our age

A stellar line up of artists reimagine some of Mitchell’s most magnificent works

Album: Taylor Swift - The Tortured Poets Department: The Anthology

Taylor Swift bares her soul with a 31-track double album

Album: Taylor Swift - The Tortured Poets Department: The Anthology

Taylor Swift bares her soul with a 31-track double album

Album: Jonny Drop • Andrew Ashong - The Puzzle Dust

Bottled sunshine from a Brit soul-jazz team-up

Album: Jonny Drop • Andrew Ashong - The Puzzle Dust

Bottled sunshine from a Brit soul-jazz team-up

theartsdesk on Vinyl: Record Store Day Special 2024

Annual edition checking out records exclusively available on this year's Record Store Day

theartsdesk on Vinyl: Record Store Day Special 2024

Annual edition checking out records exclusively available on this year's Record Store Day

Album: Pearl Jam - Dark Matter

Enduring grunge icons return full of energy, arguably their most empowered yet

Album: Pearl Jam - Dark Matter

Enduring grunge icons return full of energy, arguably their most empowered yet

Album: Paraorchestra with Brett Anderson and Charles Hazlewood - Death Songbook

An uneven voyage into darkness

Album: Paraorchestra with Brett Anderson and Charles Hazlewood - Death Songbook

An uneven voyage into darkness

theartsdesk on Vinyl 83: Deep Purple, Annie Anxiety, Ghetts, WHAM!, Kaiser Chiefs, Butthole Surfers and more

The most wide-ranging regular record reviews in this galaxy

theartsdesk on Vinyl 83: Deep Purple, Annie Anxiety, Ghetts, WHAM!, Kaiser Chiefs, Butthole Surfers and more

The most wide-ranging regular record reviews in this galaxy

Album: EMEL - MRA

Tunisian-American singer's latest is fired with feminism and global electro-pop maximalism

Album: EMEL - MRA

Tunisian-American singer's latest is fired with feminism and global electro-pop maximalism

Music Reissues Weekly: Congo Funk! - Sound Madness from the Shores of the Mighty Congo River

Assiduous exploration of the interconnected musical ecosystems of Brazzaville and Kinshasa

Music Reissues Weekly: Congo Funk! - Sound Madness from the Shores of the Mighty Congo River

Assiduous exploration of the interconnected musical ecosystems of Brazzaville and Kinshasa

Comments

To me Jimmy Cliff is the