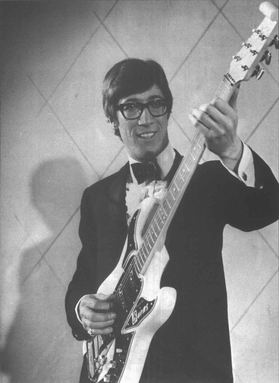

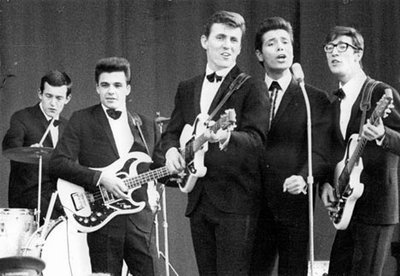

Hank Marvin (b 1941) was born Brian Rankin in Newcastle. At 16 he and his school friend, fellow guitarist Bruce Welch, headed for London to seek their fortune as musicians. They quickly found work at the 2i’s Coffee Bar in Soho, a seminal British rock’n’roll haunt. The pair were soon hired as Cliff Richard’s backing group, initially known as The Drifters and, eventually, as The Shadows. As well as accompanying Cliff Richard on early hits, the Shadows fired out a series of era-defining instrumentals such as “Apache”, “FBI” and "Kon-Tiki”. Together these releases came to sum up Britain’s take on rock’n’roll and proved hugely influential on the Beatles, Eric Clapton and many other seminal 1960s musicians.

Marvin appeared with The Shadows in iconic Cliff Richard films, such as Summer Holiday and The Young Ones, and the group maintained a career, albeit not at quite the same commercial level, as the 1960s progressed. In the early Seventies Marvin formed a vocal trio with Welch and Australian singer-songwriter John Farrar (who would later go on to have huge success with Olivia Newton John). There was a resurgence in The Shadows' fortunes later in the decade with massive sales of their greatest hits album 20 Golden Greats and chart-topping 1979 studio album (their twelfth) String of Hits. While The Shadows' career has wound down since 1990, they have occasionally reformed for sell-out tours, notably a Farewell Tour in 2004 and a 50th Anniversary Tour with Cliff Richard in 2009.

Marvin appeared with The Shadows in iconic Cliff Richard films, such as Summer Holiday and The Young Ones, and the group maintained a career, albeit not at quite the same commercial level, as the 1960s progressed. In the early Seventies Marvin formed a vocal trio with Welch and Australian singer-songwriter John Farrar (who would later go on to have huge success with Olivia Newton John). There was a resurgence in The Shadows' fortunes later in the decade with massive sales of their greatest hits album 20 Golden Greats and chart-topping 1979 studio album (their twelfth) String of Hits. While The Shadows' career has wound down since 1990, they have occasionally reformed for sell-out tours, notably a Farewell Tour in 2004 and a 50th Anniversary Tour with Cliff Richard in 2009.

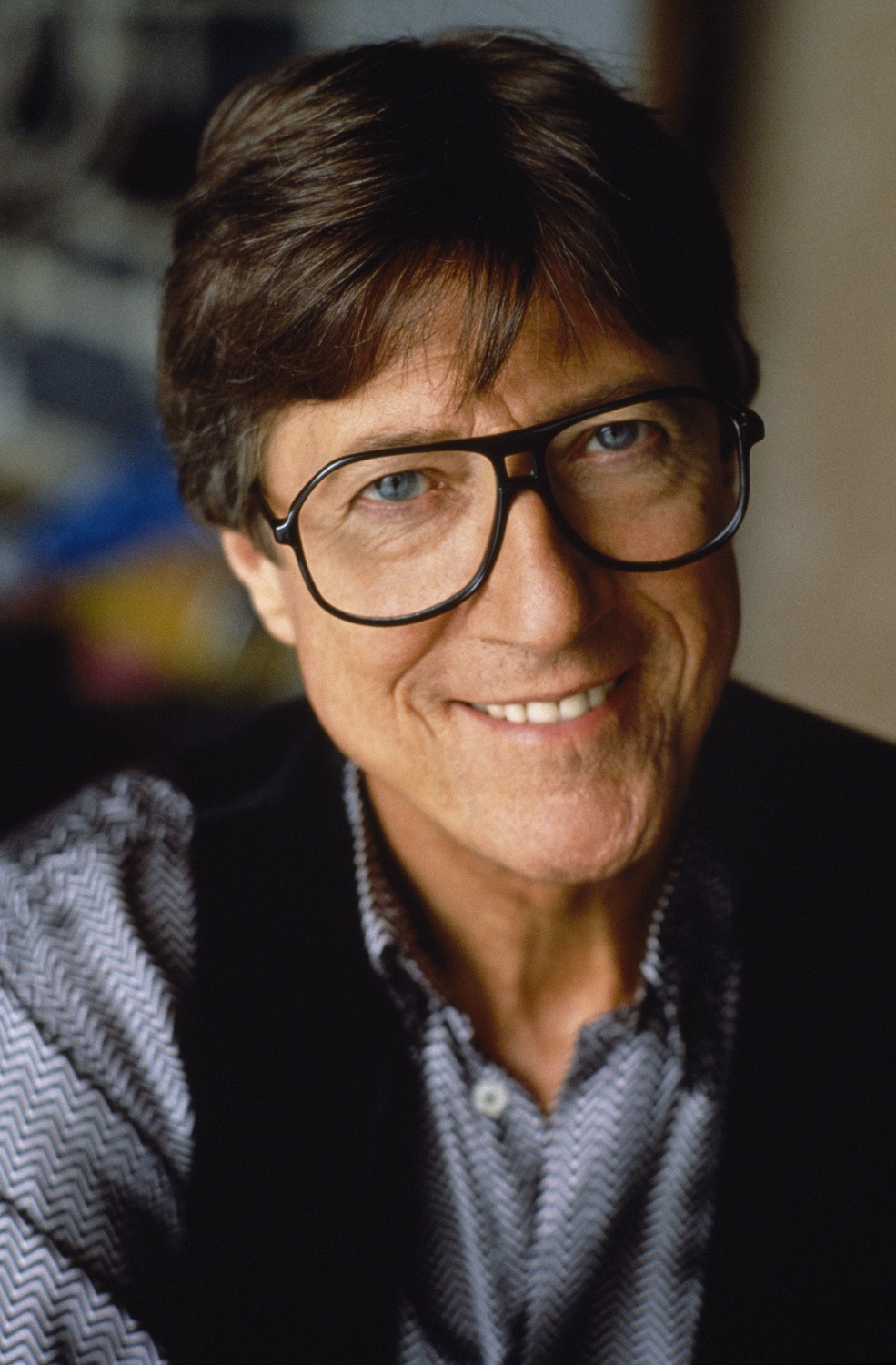

Marvin is generally regarded as one of the most influential guitarists of the early rock and pop era, the twangy sound on his most famous hits immediately recognisable, and he’s guested on records by artists ranging from Roger Daltrey to Jean Michel Jarre, as well as sustaining a solo career. His latest album, entitled simply Hank, is a celebration of summer and features arrangements by his son Ben and backing vocals from his daughter Tahlia. Marvin has lived in Australia since November 1986 and has flown into Britain to promote the release. I meet him in a record company boardroom off Oxford Street in London, one wall of which is decorated with a giant TARDIS flying through space. Marvin has a full head of brown hair, a big grin and a youthful look about him. He’s wearing belted blue jeans, a chequered shirt and a pair of large glasses, albeit not his Buddy Holly-style stage ones. He speaks with measured enthusiasm in an accent that contains light traces of both his native Newcastle and his adopted hometown of Perth.

Thomas H Green: There’s a cover of "Waterloo Sunset" on your new album. Has your path ever crossed with The Kinks?

Hank Marvin: Just a little bit, yeah. I remember in 1964 we were doing a six-to-eight week summer season in Yarmouth. They’d just started getting the hits and they did a Sunday concert there. They were shambolic, to be honest. I loved the records, I really did, but they were very raucous, needed to work on a more professional attitude. I’ve always admired Ray’s writing, he comes up with some terrific ideas. I met him once, many moons ago in Hampstead at a vegetarian restaurant. “Waterloo Sunset” is another song I’ve always liked. I felt it could work as an instrumental. Some songs don’t. They have good arrangements, good production, but when you look for the tune, there’s nothing there.

Listen to Hank Marvin's version of "Waterloo Sunset"

So you dig around songs trying to find the tune within?

I’m not going to copy the arrangement, [my version] has to do something different. "Summertime Blues" is on there. It’s not really a tuneful song but it does have a melody. I’ll give an example of a song that didn’t work out – “The Boys of Summer”. It’s a great record but when you boil it down there’s no tune.

That song is all about the lyrics, an elegy for lost youth and all that.

We kicked it around but it just wasn’t going to work. On the whole, I’m happy with the choices we made, tunes that allowed me to get some creative expression in rather than copy the original with my guitar becoming the voice. That’s what we sadly did towards the end of The Shadows' career, which I never really liked doing.

You have had more experimental periods, like in the early Seventies with your folky, vocal harmony trio

Marvin, Welch & Farrar. That gives me a fair amount of pride. We did it well, wrote some good songs. It was a rewarding time but a difficult period as we encountered resistance from Shadows fans. On the other hand a new section of the public opened up saying it was great. They’d like it then hear it was from The Shadows and some would say, “No thanks.”

Was that project influenced by the sound coming out of the US west coast?

Yes, of course. I personally have a very open mind to music. I like most music, although not all. I loved the west coast stuff, Crosby, Stills & Nash, all that singer-songwriter period.

You must have loved it when Neil Young paid you tribute on his song “From Hank to Hendrix”.

That was quite flattering. He’s good mates with Randy Bachman [of Bachman Turner Overdrive] who I've met a few times. They both started off playing instrumentals as Shadows fans. Anything like that is good for the ego. Bruce Springsteen was in Perth a few months ago. I was in the studio recording and got a call from a guy who often drives us when Cliff’s over there. He said, “I’m touring with Bruce Springsteen, and Steve van Zandt has been asking if we can contact you. He wants you to see the show.” So his PA rang and I got tickets for my wife, myself, my son and my daughter. A fabulous show and we met Steve after and he said, “Bruce wants to meet you.” There’s a photo on my phone – I had to get a photo with the Boss. Bruce told me, “When we started in New Jersey everything was instrumental. We did several gigs a week but no vocals. We did Ventures covers, some of yours, no-one wanted vocals until 1964 when the Beatles became successful.” I didn’t realise. I thought he was first and foremost a singer but, no, he started as a guitarist.

Watch Neil Young perform a (lovely) acoustic version of "From Hank to Hendrix"

You and EMI had a parting of ways in the Eighties and you re-recorded a lot of your old material for Polydor. Did this lead to confusion, people wanting the originals?

No, we acknowledged straight away we were re-recording the stuff. We tried to capture the sound of the original as much as we could but it was difficult, due to the equipment we used in those days, the recording techniques. We got quite close but it’s never going to be the same. No-one was being fooled. A lot of fans liked the way we’d revisited them but some thought we shouldn’t have. I’d be the same. I had a Little Feat album with "Rock’n’Roll Doctor" on, the original with a terrific slide guitar solo by Lowell George, very simple, very well-constructed, a cracking record. I lost it or it got nicked. I discovered the song a few years later on another album but it’s a re-recording. It’s not the same, it lost the groove, a shame.

Why did you leave EMI?

Why did you leave EMI?

The first album with Polydor was in 1981. It had reached a situation by the end of the Seventies that there was some issue about re-signing with whoever was then in charge of EMI. It was a little disappointing, for sure. It was a long relationship. Crumbs! With Cliff in 1958, then with the Shads' first contract as The Drifters in 1959, then they say they don’t want us. We felt almost discarded, especially as Golden Greats and More Hits had recently been platinum albums.

Albums sold loads then. Now anything that’s data - writing, photography, music, and so on - is free. It’s affected my finances these last five years, for instance, as a writer.

Has it?

Well, I earned more money writing when people had to buy it in physical form, with all that extra income from adverts. Anyway, I digress. Given that the same thing has happened to music, do you feel privileged to have been involved with the music business in what will likely turn out to be its all time boom years?

Definitely. Looking back to the Sixties, particularly with singles, when we were having hit records they were enormous compared to what people are selling now. It’s chicken feed.

Paltry amounts…

A friend of mine is a French guitarist and record producer. I’ve known him since he was a kid. His dad was a very popular singer in France who went into TV production. We did a TV special with the Shads and that’s when we met his son. He’s a big fan, about 40 now, a good guitar player and successful in record production. He was saying sales had gone down by two thirds in France.

Is that Jean-Pierre Danel, you’re talking about? You worked with him, didn’t you?

He asked me to do a couple of guest things on an his second instrumental album [2010’s Out of the Blues]. We did a version of “Nivram” and we did a bluesy thing, a very rough 12-bar track with a US guitarist, a wonderful jazz-fusion player.

In the early Seventies you had a hit with Cliff Richard and the song “Throw Down a Line”, a departure from both your styles.

That was round 1969. I just had this idea for a song. I wrote it and I thought I’d love to get it to Jimi Hendrix so I did a rough demo at home and took it into our office in Savile Row. Upstairs was an office where Mickie Most’s brother Dave was based, a very successful song plugger. He said, “Can I play it to Mick, he’s doing an album with the Jeff Beck Group." Rod Stewart was fronting them. Then I get a call from Mick – “I love the song – what’s that funny drum sound?” It was a terrible little Japanese drum box and all it did was go boom-clack-boom-clack. He said, “I want that sound,” so I took it down to the studio and dropped it in. I remember that night very well. It started to snow very heavily and we just made it home. I had a Porsche then with rear wheel drive. It was going really well unless you had to stop and then you skidded all over. I got a call from Mick. He said, “Hank, I really think this is a hit song but not for this band, it’s just not happening.” Lo and behold Cliff called me up and said, “Hank, I just heard that song and I think it’s great, why didn’t you play it to me?” I said, “I didn’t think it was your sort of song.” He got all huffy – “I should decide what’s my sort of song!” Then he asked, “Shall we do it together as Cliff & Hank?” It turned out pretty well in most ways. I think the arrangement could have been a little looser.

Watch a curious clip of Cliff Richard performing "Throw Down A Line" on French TV in 1969

Marvin, Welch & Farrar also did it on your first album in 1970.

Funnily enough, about a year ago Jeff [Beck] was in Perth and I went to see his show with my wife Carole and a couple of friends. He mentioned that his version of that song is now available on a compilation as one of three bonus tracks. I got the album and I could see what Mick meant. It’s a bit like a pub band idea – they didn’t get their hearts into it. I went up in my friend’s estimation enormously that night when Jeff Beck said, “You know, Hank, you’re 80% of the reason I’m playing guitar.” My friend looked at me and said, “Maybe you’re not that bad after all.”

Watch Marvin, Welch & Farrar miming "Lady of the Morning", bizarrely introduced by Ken Dodd and Roger Whittaker

Did you feel sidelined by the 1960s rock guitarists?

I remember years ago, when we started to get The Shadows back together again, we did this album called Rockin’ with Curly Leads in 1973, after Marvin, Welch & Farrar. John Peel invited us to do his show which we did. I quite admired John’s approach to radio, finding new bands, giving them exposure. He said, “I was a bit of a Shadows fan in the early Sixties but as the Sixties went on it became really uncool to say you liked The Shadows. I want to tell you something – it’s becoming cool again, we’re all coming out of the closet.” I admired the way guitar music went in the Sixties. When I was 14-15 I was really into folk-blues, which was all acoustic stuff, so when I first heard the John Mayall Bluesbreakers, I’d never heard electric guitar blues. What’s going on there? Wow! I started reading about Eric [Clapton], how he was influenced by BB King, and I bought a few of those albums to see what was going on. Peter Green, I loved his playing too.

Later rock guitarists revelled in dissonance and distortion in a way I wouldn’t associate with you. What did you make of Link Wray’s “Rumble” when it came out? That was a very early stab at that kind of sound?

Later rock guitarists revelled in dissonance and distortion in a way I wouldn’t associate with you. What did you make of Link Wray’s “Rumble” when it came out? That was a very early stab at that kind of sound?

That was in 1958 when we were playing the 2i’s coffee bar. We used to play it, in fact. Talking of distortion, it’s interesting. It’s generally perceived that the sounds I use are pretty clean, which is true, but if you listen to early Shadows records like “Man of Mystery” or “The Savage” there’s a little bit of distortion coming through an echo box and amplified which gives an edge. There are a few more like that. I did a tune with Brian May a few years ago, a version of “We Are The Champions” on my first solo album [1992’s Into the Light]. He was saying, “People think The Shadows have great melodies but forget the tougher side. When I was kid and we were buying your records and things like 'FBI' and 'The Savage' were hard rock to us.”

When I interviewed Lemmy a couple of years back, he reckoned one thing it was impossible to convey, as the years pass, is what it was actually like to experience certain moments as they happened at the time. I agree. It’s almost impossible to imagine what it was about Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring that caused a riot, people actually fighting in the theatre when it was performed in Paris in 1913. You can understand it intellectually but it’s very, very difficult to get under the skin of it, to feel it in the gut.

This is it. When I started we’d never heard those big, heavy sounds. It’s all relative to what’s gone before. What’s new to your ears can have a hard energy and a new feel. Then things did change, heavier sounds came in – Hendrix, blues-rock, Deep Purple, Richie Blackmore, I love his playing.

One change is electronic music. Like a lot of your own work, post-acid house club music is often primarily instrumental. You’ve worked with Jean-Michel Jarre [on the 1988 track “London Kid”] but do you have any affinity with techno?

When electronic music first started coming on the scene - and Jean Michel was one of the early exponents of that - I found it really exciting. It opened up a whole new world of sounds with sequencing. On some albums [with the Shadows] we started using synthesizer sounds with my guitar. With my last three albums, though, I’ve tried to go back to much more guitar-oriented stuff, leaving synths out of it. I’m not averse to them but with The Shadows we were heading too much in that direction. Every instrument produces its sound in a different way, whether a reed, blowing a pipe, strings vibrating, or hitting something. I welcome anything that makes music, but I do like the idea of sticking with non-electronic instruments.

Was the poorest time of your life when you first moved to London?

Probably, yes. I came from a working class background, never any real money. My parents would be scraping at the end of the week but they were both – particularly my mother – very good money managers, and my dad didn’t drink or gamble. But when Bruce and I came to London in April 1958 we didn’t have any work for a little while, then we started getting the odd gig at the 2i’s. The money went on bedsit rent and on train fares from Finsbury Park, where we lived, to the West End. It was a difficult period. We often couldn’t pay the rent. The lady who owned the boarding house, Mrs Freeman, was coincidentally also from the north-east. She was very kind to us and let us build up a little rent backlog which we’d pay. A few times when we had next to nothing we wouldn’t eat for couple of days. We’d literally have an apple over two days. Another time, when we had a couple of pence each, you could buy an Oxo cube for one penny and two cellophane-wrapped penny buns, little bigger than a mouthful each. You’d have it with your cup of Oxo and that was food for two days. That only lasted a couple of weeks then there was more and more work at the 2i’s, probably five or six nights a week at 18 shillings a night. That’s four or five pounds a week. The rent was two pounds so that left us enough for food.

When you hear Cliff Richard's debut single “Move It”, recorded before you hooked up with him, do ever think, “Damn, I wish I’d been on that record”?

When you hear Cliff Richard's debut single “Move It”, recorded before you hooked up with him, do ever think, “Damn, I wish I’d been on that record”?

I’d love to have been on it but I think the way it turned out was the way it should have turned out. Cliff was saying he originally booked Bert Weedon to do guitar on the session but he couldn’t so [Columbia Records arranger-producer] Norrie Paramor got guitarist and banjo player Ernie Shears. Norrie used him a lot in the Big Ben Banjo Band, which was another of his productions. Ian Samwell, who wrote the song, had done the intro as a single string line. When he showed Ernie the intro he said, “What about doing it as a double stop? [ie, playing two notes simultaneously]” A wonderful accident. If I’d been there maybe I wouldn’t have done that. The way he played guitar lines between the vocals was absolutely perfect, a cracking record. When we first heard it on the jukebox in the 2i’s we thought it was an American record.

Your own involvement with Cliff came shortly afterwards.

The first record that Bruce and I played on – and [original Shadows bassist] Jet [Harris] – was the third single. On Cliff’s first session he did “Move It”, “Schoolboy Crush” – which, can you believe it, they originally wanted as the a-side – “High Class Baby”, and whatever the b-side of that was [“My Feet Hit the Ground”]. Cliff really wanted us playing on that record but Norrie was being very cautious. He had Ernie Shears on lead guitar, Terry Smart on drums, Frank Clark on double bass, Jet Harris on bass guitar, Bruce and myself on guitars. Cliff said he’d like two versions of everything – “I’d like Hank to play lead guitar on one” - because Norrie was pushing for Ernie. We did two versions of “Livin’ Lovin’ Doll” - not “Living Doll” [which came a few months later] – “Never Mind”, “Mean Streak”, all that stuff. I had this terrible Anatoria and the only good thing about it was I could bend the second string. We did those tracks and Cliff came up and said, “I sang better on your version.” The problem with Ernie, if you listen to “High Class Baby”, he basically did the same solo as on “Move It”. He tended to do that again and again. It wasn’t going anywhere different. I wasn’t as good a player as Ernie but I think I was bringing some different ideas that might have been a bit wild and far out sometimes. Norrie was happy after that.

Listen to "Mean Streak" by Cliff Richard & the Drifters (AKA The Shadows)

Buddy Holly was a huge hero of yours. Can you recall where you were when you heard he’d died in that plane crash?

January or February ‘59 [3rd February]. I can’t remember if we were on tour but we read it in the papers. It was quite a shock to us, one of our heroes, a young guy. We didn’t really know the Big Bopper. We knew his single “Chantilly Lace” and Richie Valens, what was he? 17? It seemed such a waste, a sobering experience, to realise that any of us could be snuffed out any time, as Eddie Cochran was in a car crash a little later.

It’s a hazard of your profession. A musician is statistically more likely to be travelling often and at night and in unconducive circumstances.

Well, of course, Stevie Ray Vaughan in that helicopter crash, John Denver in a plane crash. It’s one of those things you accept. You can’t wrap yourself in cotton wool. I remember where I was when I first heard the Crickets’ “That’ll Be The Day”. I was in a coffee bar in Newcastle 15 minutes from where I lived in what was called the West Road, near our grammar school. My girlfriend lived in that area and a few of us used to hang out in that coffee bar - or milk bar as we called them, since you’d order one very milky coffee and listen to the jukebox. Suddenly this record came on and the world stopped for a while. Fantastic! I instantly became a fan of Buddy Holly.

Of all those early American rock’n’rollers one of the most troubled and troublesome was Jerry Lee Lewis. Did your paths ever cross?

I never met him. I saw him a couple of times. When “Whole Lotta Shakin’ Goin’ On” first arrived, oh man, what a great record! Bruce and I were living in London in 1958 and that summer Jerry Lee Lewis came over to do a tour. He did three concerts and then the tour was abandoned because the news broke that he was married to a 13-year-old girl [his first cousin, once removed, Myra Gale Brown]. This was perfectly legal in the States.

That fact often gets forgotten when the story is told, that taking a bride of that age was then still quite usual in the American south where he came from.

Sid Morris, sadly now dead, and David Bryce, tour managers with us in the early days, they were on the tour with him. They said said she looked about 20 years old. She had the figure of a woman, she wore make-up, very composed, you’d have thought she was a woman if you didn’t know, then it suddenly broke, and boom! Fortunately, before that happened, we went to see him at the [Gaumont] State in Kilburn. Coincidentally Cliff was there but we hadn’t met at that point. It was a good show. He was a very rock’n’roll performer in his ermine-lined jacket, combing his hair on stage. He really got up the nose of the teddy boys because he was so flash and he put his foot up on the piano. But it was good rock’n’roll and he sang well and pumped the piano. When we had the digs in ‘58 in Finsbury Park one of the guys who had roomed there worked on the ships and he came back with a Jerry Lee Lewis record. The label said Jerry Lee Lewis and his Pumping Piano. Then in ‘68 I went to see him again. I was talking about this yesterday. It was somewhere near Cromwell Road, a small place and he was as close as you are to me.

He’s still around.

Is he really?

Yep, last man standing. Can you tell us a little about your involvement in gypsy music.

Yep, last man standing. Can you tell us a little about your involvement in gypsy music.

I had an album back in 2002 called Guitar Player, all acoustic. Then I started listening to Django Reinhardt. Crumbs, I hadn’t listened to Django and Stéphane Grappelli since I was about 17. I really liked getting back to it again, back to the origins of modern music, a simple little band with fantastic playing from Django and Stéphane. I started listening to modern gypsy players, gypsy swing, and bought myself a gypsy jazz guitar, a French Favino made in the style of the Selmers Django used but with a slightly bigger body. I asked a guy called Gary Taylor, who used to be in The Herd with Peter Frampton, and has played bass and guitar on a few of my albums, whether he fancied learning a few of these gypsy jazz numbers. We did a charity show and some people who ran a local jazz club asked if we’d like to play. We made an album, Django’s Castle, but it’s only available through CD Baby or iTunes, and we toured New Zealand which was great. They didn’t know what to expect but they weren’t just shouting out for “Apache” which was encouraging, as it can sometimes happen with Shadows fans.

Ah, “Apache”, now you’ve brought it up, was it frustrating when Jorgen Ingmann’s version was a huge success in the States rather than The Shadows' original?

Of course it was. In those days Capitol would release our records, from “Apache” on. Their attitude was they weren’t going to promote it as we were just doing American music anyway. Now this record had been a hit around the world. We released it in America and they didn’t promote it. We’ve met Jorgen a few times - he’s Danish, by the way, and very good guitarist. He told us the story about ten years ago. What happened was he did this deal with Arrow records, a small company, he had this song called “Echo Boogie” and they were looking for a B-side. He said, “I got my mail out and this little package had a white label in which just had 'Apache' written on it. I now know it was your version, which I didn’t at that point as it hadn’t been released in Denmark." His record company thought he should record it so he added some arrow sounds and it was promoted in America where it was Number One for some weeks [it actually reached Number Two but was a big seller].

Watch an early Shadows promo film for "Apache"

You were in good company as even The Beatles' early singles weren’t promoted in the States at first.

Yes, their first four singles, which I thought were wonderful, received no promotion over there, until the big hyped up campaign for “I Want To Hold Your Hand”, then – bang! – suddenly five records in the Top Ten. We couldn’t afford to go over there – go there for five or six months and you’ll happen but Peter Gormley, who was our manager, said what we need to do is consolidate success in other territories where we’d already got hits. He was right. The whole of Europe turned out to be equivalent to America for us.

Jerry Lordan wrote “Apache” and some of your other hits. His career hit the skids but you persistently remained supportive of him, giving him work. Was that because he was a friend or just down to his talent?

He was a talent. Think of the Sixties tunes he wrote for us – “Apache”, obviously, “Wonderful Land”, “Atlantis”, great tunes, very different to what was going on at the time. To me “Wonderful Land” is a majestic melody. He wrote a thing called “Mustang” on an EP that should have been a single, he wrote “Diamonds” for Jet Harris & Tony Meehan, as well as “Scarlett O’Hara” and “Applejack”, all sizeable hits. He had an unfortunate marital situation that really dragged him down emotionally and he dried up, but came back a little at the end of the Sixties when they split up. He came to me and said, “We’ve written this thing you should record, called 'Sacha'.” I said, “Why’s it called that?” “Because we started writing it as a song for Sacha Distel but it’d be a great instrumental.” You couldn’t get airplay in the UK for an instrumental in the late Sixties, unless it was from a film, but for some reason it took off in Australia and became the biggest record of 1969 [released in September 1969, it was Australia's 80th best-selling single of 1970]. He wrote a few more, a couple for Cilla Black and for Cliff in the Seventies. Sadly he’s dead now. He died of kidney failure

You have a very good memory for detail. Do your religious beliefs [Marvin is a Jehovah’s Witness] mean you don’t drink?

Oh, no, I love wine. Mormons and Seventh Day Adventists are supposed not to drink but there’s no scriptural basis for that.

They like a drink in the Bible, don’t they?

Exactly. Jesus turned water into wine. I enjoy wine very much. I had some last night.

I used to know a Jehovah’s Witness. She didn’t buy Christmas presents but she’d always have a gift for you in early December of January. Is that how you do it?

Yes. Our view is you buy someone a gift because you want to buy them a gift not because you’ve got to buy them one at Christmas. Christmas was never celebrated by the early Christians, it was unknown to them and several centuries before it became a festival. It was to do with Winter Solstice – giving gifts, the trees, the partying, it’s all part of pagan religion. That’s the reason we don’t celebrate, not because we don’t enjoy a good time… within reason.

You seem happy talking about issues relating to your religion. I'd heard it might be a prickly subject.

I don’t mind touching on it. The only thing is I feel sometimes on a radio show that listeners might think, “Here we go again, he’s going to start preaching,” but I’m not there to do that. I’m there to discuss other things.

In the mid-Sixties Cliff Richard and The Shadows were heavily involved in pantomime. Given that this could be perceived as the antithesis of rock’n’roll, how did that make you feel?

I'll tell you what happened. In 1964 Pete Gormely, our manager, said they want you and Cliff to do a pantomime at the London Palladium that will start in ’64, running into ‘65. They want you to write the music as if it were a musical. It was Aladdin and His Wonderful Lamp and we wrote that during the summer season in Yarmouth in 1964. I remember Mick Jagger came to see the show one night. He thought it was charming and said, “You guys are really lucky, you can be here for weeks while we’re schlepping round doing one-nighters.” Look, it was fun. I have to be honest that doing two shows a day for three and half months, five or six numbers a show, after a while you think, “This is not what we signed up for.” We wanted to play music instead of fooling around. The novelty wore thin after a few weeks but then you look at your bank balance and it’s OK. We did one for Frank Ifield the following year, and for ’66-'67 we wrote a third one, Babes in the Wood. The positive side was it really stretched us to write songs that would carry the plot along. We also wrote things like “In The Country”, so we had a few hits from it too.

The films you made with Cliff have had double, even triple lives. The TV show The Young Ones, for instance, was named after the film and regularly mined those films for comedy. Have you enjoyed such post-modern perspectives?

They did a single with Cliff and I guested on it, revisiting my guitar solo. It was a charity thing and was fun. When people do it well and with a bit of affection, but see the funny side, that’s good, although we’ve all been in a situation where people have probably mocked or ridiculed, which is fair enough too as we’re all fair game.

It’s the innocence those films portray that they’re fascinated by. Do you watch them with your children and grandchildren?

They have seen them. I saw some of The Young Ones last Christmas. I hadn’t seen it for 15 years. It was funny looking at that. You’re an old fart and you look at yourself on the screen. There you are aged 19 or so. It’s quite a thing.

Watch a trailer for The Young Ones

Add comment