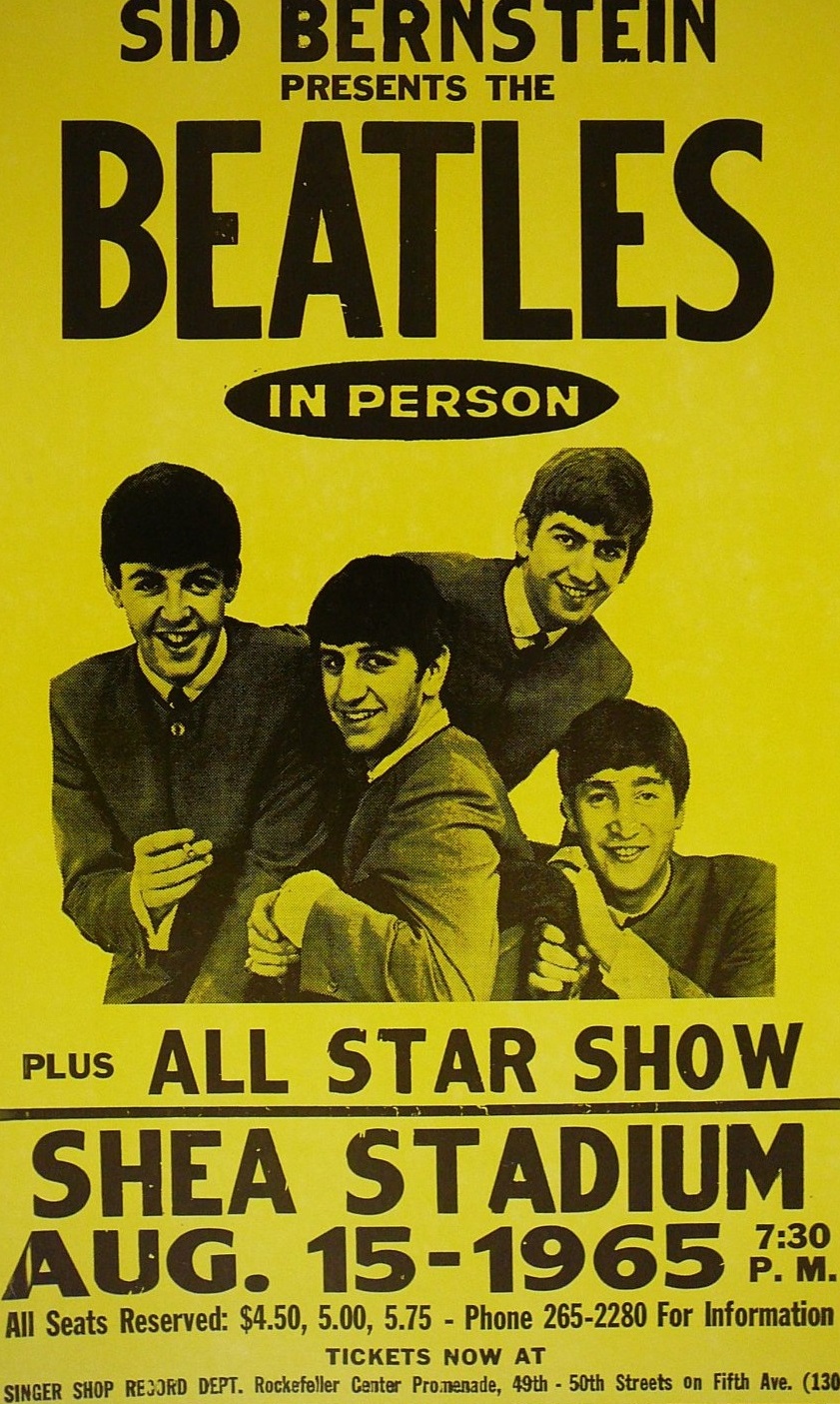

Half a century ago today, on a warm August Sunday night in New York, The Beatles played a 30-minute concert in a baseball field. Home to the New York Mets the venue was called the William A Shea Municipal Stadium and had opened in spring 1964.

In January 1965 Beatles manager Brian Epstein and US promoter Sid Bernstein had struck a deal to present the boys in the largest space they’d played in: it would be the first gig of the third US tour, and remained, by far, the biggest live event The Beatles ever did. It was, indeed, at the time the biggest instance of outdoor entertainment in history. A new Kindle Single The Beatles Play Shea by James Woodall tells the story of the concert and what led up to it.

Here is his account of The Beatles’ arrival in New York and that astonishing half-hour…

One thousand screamers gathered at London Airport to see The Beatles off to the United States on Friday 13 August 1965. Reception at JFK was non-existent. Fans had been advised there’d be little to see. The Beatles disembarked in a protected zone.

One thousand screamers gathered at London Airport to see The Beatles off to the United States on Friday 13 August 1965. Reception at JFK was non-existent. Fans had been advised there’d be little to see. The Beatles disembarked in a protected zone.

In Manhattan, the entourage stayed at the opulent Warwick Hotel on West 54th Street, where the four survived the standard packed and hectoring press conference (with Tony Barrow as M/C). Eighteen full north-American days and 10 shows lay ahead. The schedule was to be more leisurely than the two previous visits. The four men were effectively transatlantic old hands, but on eager form. Girls and groupies were everywhere (ruses on their part to gain forbidden access to The Beatles’ suites still potential grounds, one imagines, for a thousand new books – all by old ladies now). The Beatles themselves needed to go in search of nothing, least of all sex: everybody and everything came to The Beatles. Yet if anything, there were even more police than ever: in corridors, stairways, lobbies and doorways, and out on the highways...

In another direction things had shifted significantly since 1964. Musically, The Beatles ruled America.

TV work for chat-show host Ed Sullivan took up most of Saturday. The result was broadcast in September, when The Beatles were back in England. For the Sunday-evening concert, promoter Sid Bernstein had prepared infrastructure as best he could.

TV work for chat-show host Ed Sullivan took up most of Saturday. The result was broadcast in September, when The Beatles were back in England. For the Sunday-evening concert, promoter Sid Bernstein had prepared infrastructure as best he could.

If he’d done his sums right, around 55,000 were expected. This was already being trumpeted as the largest gathering in recorded history for any such live show or comparable entertainment. To control that number, 2,000 security personnel were dragooned in: it was almost certainly 2,000 too few. In the surviving Shea footage it’s interesting to see how many frames crawl with dark-blue-uniformed and seemingly exhausted cops attending to or restraining fans, or running after them as they try to reach the stage; one cop wipes sweat from his forehead, incredulous at what he’s got himself into, another palms his ears as The Beatles emerge from a passageway in to the amphitheatre. The screaming was like the noise of a new model of jet-engine. From space, the flashes of cameras must have seemed to have been creating within Flushing Meadows another small city.

The plan had been for a helicopter to land on the playing field so that The Beatles could scamper straight out of it and up on to the purpose-built square stage. Security had decreed otherwise. They were thus driven in a limousine from the Warwick to a downtown heliport. From there, a white, red and blue Vertol helicopter flew the entourage to the roof of the World’s Fair building in Queens. (Footage from the TV film shows the team, Epstein in dark glasses, peering through the windows at the vertiginously jagged New York skyline.) As they were flown, Shea was being warmed up by the acts that would follow The Beatles on the imminent nine-city tour: Brenda Holloway, Curtis King, Cannibal and the Headhunters, Sounds Incorporated. The latter in particular wowed the Shea crowd, there naturally for one reason and one reason only. The kids had been told at the start of proceedings that The Beatles were “on their way” and the screech of anticipation was already fearsome.

'I feel on that show John cracked up. He went mad; not mentally, but he just got crazy,' Starr would say

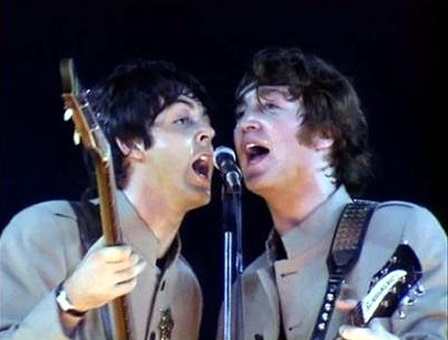

From the World’s Fair building a Wells Fargo armoured van drove The Beatles to the stadium and its back-stage entrance. In the van they’d each been given a gold-star Wells Fargo agent badge. These they pinned to a brand-new piece of apparel: pale-fawn, collarless Nehru jackets (with epaulettes), so named after the stylish garment sported by the first leader of independent India, Jawaharlal Nehru (he’d died a year and a half before). (Beatles and John Lennon biographer Philip Norman prefers: “British army tunics from the Boer War period”.) Their trousers were dark, they wore no ties, and never again live (for cameras turning) would they look quite so appealingly carefree: Beatles not unplugged, but unleashed (Paul and John duet, pictured above right).

On the platform Ed Sullivan, a cross between an ageing Richard Nixon and transatlantic TV interviewer David Frost, but dapper in blue, had prepared the best spoken words of the evening – and now, as we hear them, surely of the entire music year, if not the decade... “Ladies and gentlemen, honoured by their country, decorated by their Queen, and loved here in America, here are The Beatles.”

The sound that followed these words ripped the sky. At 9.16 pm the four erupted from a tunnel through a huddle of cops and security officials, John, Paul and George holding guitars. (The Beatles head for their stage at 2nd base in the vast Shea Stadium, pictured top left by Robert Whitaker for NYT) “Here they come!” added Sullivan pointlessly – the phrase lost in the human-jet decibels. Waving in all directions, The Beatles more trotted than ran to the stage. They shimmied up the steps, shook hands with Sullivan, plugged in and tuned up.

Ringo, as usual, took his place on an elevated drum dais.

Not much in the next half-hour went that well.

Not much in the next half-hour went that well.

For the majority of spectators The Beatles must have appeared like figurines on a smartphone screen, though that didn’t stop thousands of girls, half a dozen or so seen in close-up in the footage, beseeching whichever Beatle they wanted to enter their lives as if John, Paul, George and Ringo were – or shortly would be – in their kitchen or bedroom. Many fainted. Some seemed content to clutch and almost impale themselves against wire fencing. In the film, a pretty blonde in red is actually smiling (not crying) and jiving rhythmically to “Can’t Buy Me Love” (she’s there again in “I’m Down”): rare conduct.

Police and security were assailed constantly by rogue fans breaking out of the seating area and on to the grass, trying to outrun the cops in a mad game of Beatlemaniac tag. Who was listening to the music? It barely mattered – and of course The Beatles couldn’t really hear themselves or any one of them any of the other three. (Young women fainting was standard at all Beatles concerts, pictured below right by Jim Hughes for NY Daily News.)

New 100-watt amplifiers designed specially for the band by Vox – “…up from the 30-watt amp to the 100-watt amp and it obviously wasn’t enough…”, Harrison recalled with some contempt – were utterly unable to compete with the screaming and would have sounded pretty tinny in that space even without the crowds. The band were then connected to the arena’s PA system, which was not an improvement.

To that extent, it’s remarkable that a single one of the 12 songs held together – and they did – a tribute not least of all to Starr, who claimed that he had to look at his colleagues’ bottoms to work out what rhythm was being followed when. It seems just as likely that the six young ears of the three with guitars were listening very hard to what was coming directly from the dais behind them.

It was Starr who eventually made one of the acutest observations about Shea’s effect on the group.

It was Starr who eventually made one of the acutest observations about Shea’s effect on the group.

“I feel on that show John cracked up. He went mad; not mentally, but he just got crazy.”

There are three traceable instances of Lennon going fairly off piste at Shea. When introducing “Baby’s in Black” – “We’d like to do a slow song now” – he spoke some gibberish; he did the same again before “A Hard Day’s Night”, this time throwing out and shaking his arms, tipping his head to the sky, a gesture almost of abandoning the cause: what are we doing here? Why are we playing? In the middle of the last number, “I’m Down”, he and Harrison barely able to concentrate for laughing, Lennon in his keyboard solo seemed to leap at the Hammond organ, as if to skewer it, and played the keys, up and down, with his right elbow. If he wasn’t technically going mad, Lennon was certainly beginning, openly, to misbehave: being a Beatle was beginning to get to him (as it was somewhat to Harrison, though not at all to McCartney and Starr) – and thereby hangs a long tale…

McCartney, who probably never enjoyed singing “I’m Down” as much as he did that night, spotted Lennon’s antics and, marvellously, did his own thing: took on his feet a full 360-degree swivel of euphoria. “I’m Down” was arguably the best thing they did in that whirlwind 30 minutes, topping what they all must instantly have recognised as the most thrilling half-hour of their lives. Lennon might have reached his own precipitous edge but he knew exactly what heights The Beatles had just conquered: “It’s the top of the mountain, Sid…,” he said to Bernstein afterwards, “top of the mountain.”

In the end it all sounded alright! This wasn’t The Beatles as they wanted to sound but when forced to perform in circumstances resembling a musical battlefield they shook, they rocked, they roared and took the kids on. Who won on the night? It doesn’t matter. The night was an explosion of total Beatles theatre, exceptional even by the standards of theatre the world until 1963 hadn’t known existed. On 15 August 1965 The Beatles powered that special brand of theatre, that charisma, fearlessness and originality, into history.

Then, they left the Shea Stadium stage and were bundled into a white limo.

Fifty-five thousand six hundred people are recorded as having been at Shea. Among them were two future Beatle wives, Linda Eastman and Barbara Bach, as well as Mick Jagger and Keith Richards. It was a world record for concert attendance that stood until a less agreeable but electronically mightier quartet than The Beatles – Led Zeppelin – broke it by 1,200, in Florida in 1973. Shea box-office takings were $304,000. The Beatles’ share was $160,000: today, $1,207,898.

The concerts would continue, the earnings multiply, the music move on, the drugs become stronger, and, in 1966, the public madness intensify, even into violence and discord. The Beatles were back at Shea a year and one week later, but playing to a smaller audience and in a sourer US atmosphere: six nights later they quit the live professional stage forever.

Add comment