The Tinderbox review – a call for peace | reviews, news & interviews

The Tinderbox review – a call for peace

The Tinderbox review – a call for peace

Steeped in history, Gillian Moseley's documentary seeks to press reset on the most fervent of conflicts

The beginning of the Israeli-Palestine conflict is officially dated to 7 June 1967, the occasion of the Israeli occupation of the West Bank, including East Jerusalem, during the Six-Day War, but its origins stretch back further.

The Palestine War, recognised by Israel as the War of Independence, and by Palestinians as the Nakba (literally, "catastrophe"), took place between 1947 and 1949, and it was nearly three decades earlier that the Mandate for Palestine was assigned, in 1918. For the date of the First Zionist Congress, held in Basel, Switzerland, you need go as far back as 1897.

Whatever your metric, the intractable conflict is now the longest in modern history, a fact borne out in the substantial backlog of films that have sought to depict, and unpick, its complexities. In many cases, the title of these films alone supplies a more-than-vivid picture of the situation on the ground. Take for instance: All Hell Broke Loose (1995), Checkpoint (2003), Persona Non Grata (2003), or The Law in These Parts (2011). Unmindful of culture’s accusative cry, however, war in Israel-Palestine rages on. Far from cooling, relations between each party threaten yet more energy: issued back and forth between Israel and Gaza, the air and rocket strikes witnessed during 2021 were among the worst for a decade.

Perhaps cinema has gone about things in the wrong way? “There’s a fair amount of either fatigue or just complete confusion around the issues that surround Israel-Palestine,” admits Gillian Moseley, a diaspora Jew raised as a Zionist, when speaking to the University of Oxford Middle East Centre podcast in April of last year. “But when I went to look for a film that I could recommend that could encapsulate the situation fairly quickly, I couldn't find one.” Building upon her more than two-decades long career as a producer, Moseley’s first turn to direction, The Tinderbox, is an attempt to address that absence. Assembled for the benefit of “people who know nothing”, this on-screen archaeology of the conflict’s origins seeks to brush away the dust of bias and disinformation that has come to obstruct our efforts towards peace.

To launch her excavation, Moseley's documentary leans impressively upon a technique that cinema alone can execute: a split-screen, in which footage old and recent is thrust side-by-side, present reunited with past, and the perpetual state of crisis underlined. Then, as now, a rocket is launched, soldiers mobilise in the streets, an innocent victim is laid upon a stretcher. The conflict in Israel-Palestine political is ultimately a political crisis, but it is also a personal one. “I was taught that Jews have the primary right to claim the Holy Land,” Moseley tells us. It was a chance encounter with a Palestinian at university, she reveals, that “ruptured my unquestioning entitlement.”

The Tinderbox proceeds not through shock, or gore, but with a barrage of historical facts. “I’ve found British hands all over the beginning of this story,” Moseley reveals fewer than ten minutes in, reminding us that Jews and Palestinians aren’t the only actors in this drama. Audio readings of landmark Parliamentary speeches enliven her audience to the meat that underpins this allegation, none more so than Arthur Balfour’s infamous declaration of 1917, in which he confirmed the British Government’s support for “the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people”. Here, Moseley’s historicizing is clarifying; elsewhere, it feels desperate, such as in her appeal to the Jews’ and Palestinians’ common Canaanite heritage. To the realist, biology is unlikely to broker a peace treaty.

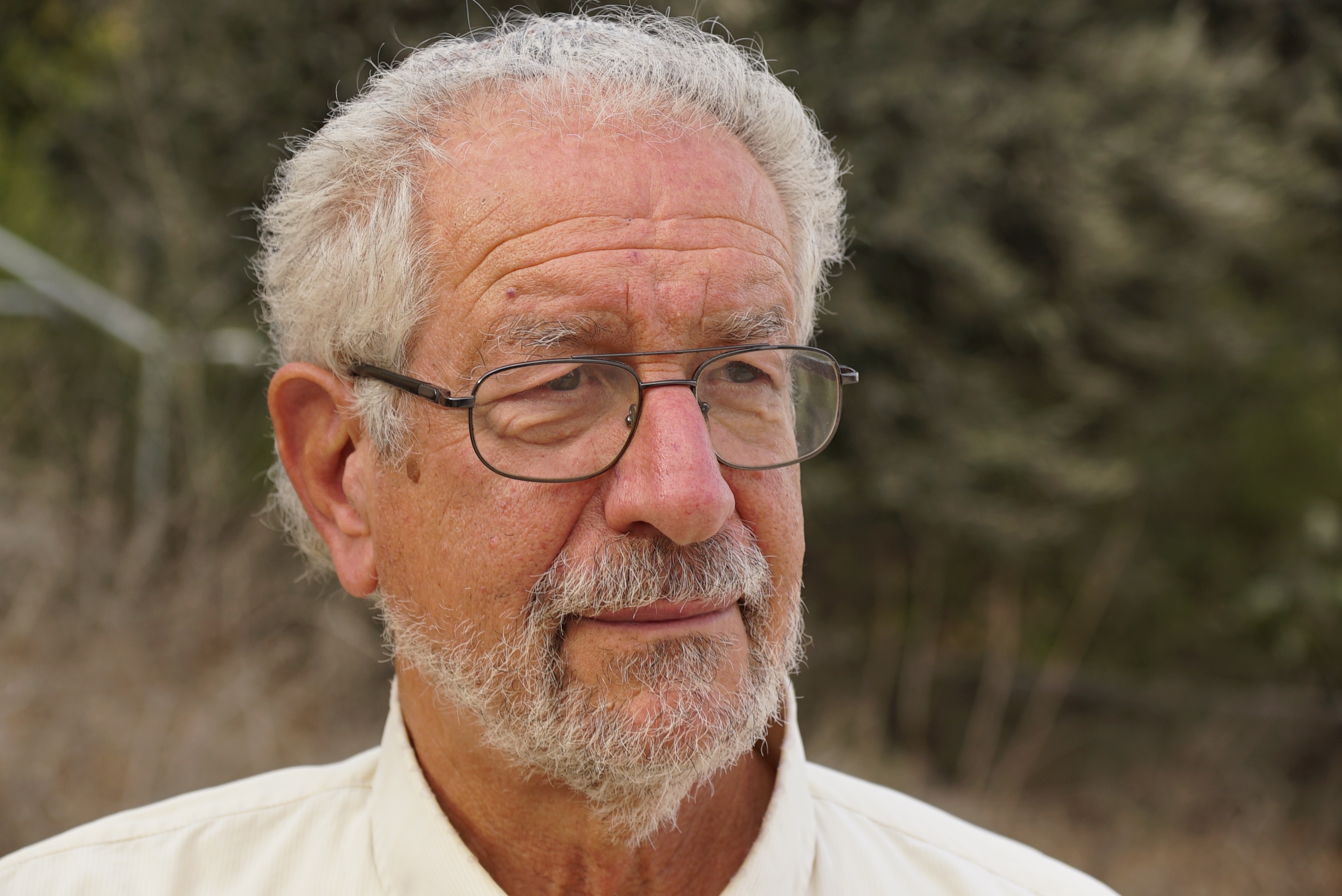

As in cinema, so in literature. It was only last year that the longlist for the International Booker Prize featured Minor Detail (2020), Adania Shibli’s vivid characterisation of the life of a Ramallah-based Palestinian who, thanks to a stolen identity card, braves an Israeli checkpoint en route to a local history museum. Meandering across Israel, The Tinderbox seeks out individuals not unlike Shibli’s protagonist and narrator, giving voice to those whose lives fall on either side of this geo-political fault line. Among them: Yisrael Medad (pictured above), a New-York born spokesperson for the Israeli settler movement. “It’s not there simply because we don’t like Arabs,” Yisrael demurs, when probed on the concrete wall that cements Gaza’s ghetto-like status. “It’s because we don’t like violence done against us.”

As in cinema, so in literature. It was only last year that the longlist for the International Booker Prize featured Minor Detail (2020), Adania Shibli’s vivid characterisation of the life of a Ramallah-based Palestinian who, thanks to a stolen identity card, braves an Israeli checkpoint en route to a local history museum. Meandering across Israel, The Tinderbox seeks out individuals not unlike Shibli’s protagonist and narrator, giving voice to those whose lives fall on either side of this geo-political fault line. Among them: Yisrael Medad (pictured above), a New-York born spokesperson for the Israeli settler movement. “It’s not there simply because we don’t like Arabs,” Yisrael demurs, when probed on the concrete wall that cements Gaza’s ghetto-like status. “It’s because we don’t like violence done against us.”

Muna Tannous, meanwhile, is a schoolteacher, and one of an ever-declining number of Palestinian Christians. “I really feel sorry for the Jews,” she says, reflecting on their experience of the holocaust. “But does that give them the right to take over my homeland? I don’t think so.” Muna gestures towards what is a theme of perpetual concern throughout The Tinderbox: of Jews having turned their back on their own history of oppression. Citing memories of dinner-table friction, Moseley explains that her own family, like many within the faith, straddles the divide between consent towards, and critique of, the Israeli occupation.

Although The Tinderbox falls in the latter category, space is reserved for the viewer to make up their own mind about this “epidemic of finger-pointing”, and who, if anyone, might lay claim to a moral high ground. Less activist, more educator, instead Moseley’s strategy is to instruct her audience in the need for dialogue. It remains to be seen whether anyone is listening.

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Film

Bugonia review - Yorgos Lanthimos on aliens, bees and conspiracy theories

Emma Stone and Jesse Plemons excel in a marvellously deranged black comedy

Bugonia review - Yorgos Lanthimos on aliens, bees and conspiracy theories

Emma Stone and Jesse Plemons excel in a marvellously deranged black comedy

theartsdesk Q&A: director Kelly Reichardt on 'The Mastermind' and reliving the 1970s

The independent filmmaker discusses her intimate heist movie

theartsdesk Q&A: director Kelly Reichardt on 'The Mastermind' and reliving the 1970s

The independent filmmaker discusses her intimate heist movie

Blu-ray: Wendy and Lucy

Down-and-out in rural Oregon: Kelly Reichardt's third feature packs a huge punch

Blu-ray: Wendy and Lucy

Down-and-out in rural Oregon: Kelly Reichardt's third feature packs a huge punch

The Mastermind review - another slim but nourishing slice of Americana from Kelly Reichardt

Josh O'Connor is perfect casting as a cocky middle-class American adrift in the 1970s

The Mastermind review - another slim but nourishing slice of Americana from Kelly Reichardt

Josh O'Connor is perfect casting as a cocky middle-class American adrift in the 1970s

Springsteen: Deliver Me From Nowhere review - the story of the Boss who isn't boss of his own head

A brooding trip on the Bruce Springsteen highway of hard knocks

Springsteen: Deliver Me From Nowhere review - the story of the Boss who isn't boss of his own head

A brooding trip on the Bruce Springsteen highway of hard knocks

The Perfect Neighbor, Netflix review - Florida found-footage documentary is a harrowing watch

Sundance winner chronicles a death that should have been prevented

The Perfect Neighbor, Netflix review - Florida found-footage documentary is a harrowing watch

Sundance winner chronicles a death that should have been prevented

Blu-ray: Le Quai des Brumes

Love twinkles in the gloom of Marcel Carné’s fogbound French poetic realist classic

Blu-ray: Le Quai des Brumes

Love twinkles in the gloom of Marcel Carné’s fogbound French poetic realist classic

Frankenstein review - the Prometheus of the charnel house

Guillermo del Toro is fitfully inspired, but often lost in long-held ambitions

Frankenstein review - the Prometheus of the charnel house

Guillermo del Toro is fitfully inspired, but often lost in long-held ambitions

London Film Festival 2025 - a Korean masterclass in black comedy and a Camus classic effectively realised

New films from Park Chan-wook, Gianfranco Rosi, François Ozon, Ildikó Enyedi and more

London Film Festival 2025 - a Korean masterclass in black comedy and a Camus classic effectively realised

New films from Park Chan-wook, Gianfranco Rosi, François Ozon, Ildikó Enyedi and more

After the Hunt review - muddled #MeToo provocation

Julia Roberts excels despite misfiring drama

After the Hunt review - muddled #MeToo provocation

Julia Roberts excels despite misfiring drama

London Film Festival 2025 - Bradley Cooper channels John Bishop, the Boss goes to Nebraska, and a French pandemic

... not to mention Kristen Stewart's directing debut and a punchy prison drama

London Film Festival 2025 - Bradley Cooper channels John Bishop, the Boss goes to Nebraska, and a French pandemic

... not to mention Kristen Stewart's directing debut and a punchy prison drama

Ballad of a Small Player review - Colin Farrell's all in as a gambler down on his luck

Conclave director Edward Berger swaps the Vatican for Asia's sin city

Ballad of a Small Player review - Colin Farrell's all in as a gambler down on his luck

Conclave director Edward Berger swaps the Vatican for Asia's sin city

Add comment