theartsdesk Q&A: Writer/Director David Leland | reviews, news & interviews

theartsdesk Q&A: Writer/Director David Leland

theartsdesk Q&A: Writer/Director David Leland

The leading film-maker on a career made in Eighties Britain

David Leland (b 1947) has worked extensively both sides of the Atlantic but he is best known, both as a writer and a director, for his shrewd observations of ordinary people struggling against the constraints and hypocrisy of the accepted social mores of English life in films such as Mona Lisa (1986), Personal Services (1987) and Wish You Were Here (1987). However, it was Made in Britain (1982), a television play written by Leland for Channel 4 and directed by Alan Clarke, that first brought Leland widespread acclaim and the story of Trevor, a sociopathic skinhead, indisputedly destined for a life of incarceration, is assured of its place in television history.

Made in Britain is, however, one of a quartet of films written by Leland – the others are RHINO, Birth of a Nation and Flying into the Wind - collectively known as Tales Out of School, which explore Britain’s attitudes to education and individuals like Trevor who, for whatever reason, fall through the (very holey) net.

RHINO (which is social services speak for Really Here in Name Only) follows a teenage truant whose cack-handed treatment at the hands of her well-meaning but ineffectual social workers destroys any chance she might have had of a future. In Birth of a Nation, directed by Mike Newell, a remarkably fresh-faced but reassuringly brilliant Jim Broadbent plays a newly qualified teacher, shocked by the old-fashioned, authoritarian teaching methods he discovers when he joins the staff of a comprehensive school, and Flying into the Wind depicts the battle between parents who wish to home-educate their children and the local education authority.

RHINO (which is social services speak for Really Here in Name Only) follows a teenage truant whose cack-handed treatment at the hands of her well-meaning but ineffectual social workers destroys any chance she might have had of a future. In Birth of a Nation, directed by Mike Newell, a remarkably fresh-faced but reassuringly brilliant Jim Broadbent plays a newly qualified teacher, shocked by the old-fashioned, authoritarian teaching methods he discovers when he joins the staff of a comprehensive school, and Flying into the Wind depicts the battle between parents who wish to home-educate their children and the local education authority.

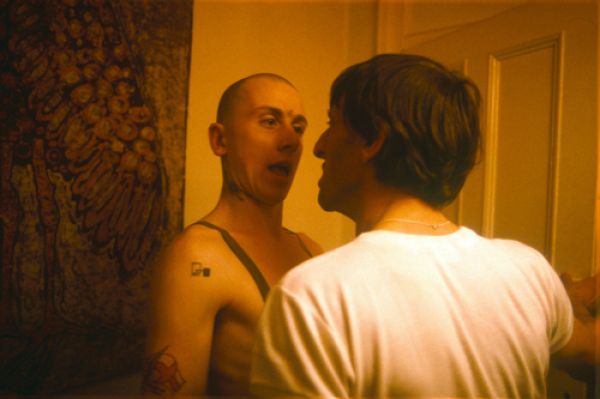

David Leland talks to theartsdesk about his career as an actor, writer and director, including how he came to write Tales Out of School – which will be released on DVD next week (pictured above, Tim Roth as Trevor).

HILARY WHITNEY: Although Tales Out of School was made nearly 30 years ago and there are some obvious differences – no online bullying, no texting during classes – all four of the films are still remarkably relevant today.

DAVID LELAND: I think there are added elements today but looking at the films again, I would agree with you. I hadn’t seen the material for a long, long time and I thought they stood up incredibly well. One of the great differences, of course, is that we don’t have corporal punishment in schools any more and I’d like to think we did our bit to help stop that with Birth of a Nation. I’d spent time with a man called Tom Scott who ran an organisation called STOPP, the Society of Teachers Opposed to Physical Punishment and I think if I had an axe to grind in any of the films then it would be the violence that adults assert against children at school – and at home. It’s something I’ve always felt terribly strongly about.

Where did the idea to make four films about education come from?

I’d just been working on a Play for Today called Beloved Enemy (1981) with Alan Clarke which was about how, at that time, the Eastern Bloc was trading with the West and how multinational companies were building factories inside Russia and Poland and so on. We then decided we wanted to do a film about the politics of famine, what actually happens to money once it goes into areas where there is famine, so Alan took that idea to Margaret Matheson who had just become the Controller of Drama at Central Television – they had a history because Margaret had produced the original production of Scum (1979), the one that the BBC wouldn’t show. She wasn’t interested in that idea, she was looking to do something about children and education, so Alan said, “Oh, you can talk to Dave about that because he’s been going at me about wanting to do a film about people who won’t send their kids to school and want to educate them at home."

Why did that appeal to you as a premise for a film?

I’d met a family – they were friends of friends - who were part of an organisation called Education Otherwise and were educating their children at home. This family had been under threat for years from the local education authority in Herefordshire who were trying to put the children into care because they were not going to school. This was all being done in the name of the Education Act [1944] - “Parents must guarantee their children are in full-time education in a school or” – the crucial phrase at the end of it – “otherwise,” and, like the family in the film, these people had to appear in the Crown Court to appeal against the local authority from taking their kids away.

They were a unique family because again, like in the film – there was a lot in the film about them - the boy couldn’t read but he knew everything about car engines and his sister had difficulty in reading but she was a very skilled plumber. They had different kinds of skills and a different kind of educational regime and I became very interested in what they were doing so I was pursuing it privately as a possible subject. Anyway, I talked about that, just as I’m talking to you now, to Margaret over the phone and I said, “And there are whole other areas I’d like to explore, like corporal punishment,” so we talked, not for that long but we instantly clicked and at the end of the call she said, “Right, you’re on. I’m new here, I’ve got carte blanche to do what I want so what do you want to do? Do you want it to be like a soap opera? Do you want to run it for 12 weeks, 20 weeks, what do you want? You can have an hour every week or we can do it like Z-Cars – whatever you want.” I was stunned. So I said, “I’d like to go away and think about it. I need to do more research and broaden the subject.” She said, “Fine – I’ll pay you to go and research it."

That wouldn’t happen now, would it?

Well, exactly. I am making a broader point about how we get things made on television. You need people like Margaret Matheson – imaginative people with inspirational minds. Look at the BBC in Northern Ireland when Alan Clarke was making films like Elephant [1989] – who was running it? Danny Boyle.

So I went away and did research and thought about it. I wanted to find out more about social services so I befriended a social worker called Harry who then, during the course of my research and also while I was writing, took me everywhere. He took me to places where I wasn’t allowed to go really – juvenile courts, lock-ups, secure units and all of that and whenever we walked in, he’d just say, “This is David, he’s a trainee,” and as soon as he said that, I became the invisible man because nobody is interested in a trainee. Eventually I went back to Margaret and said, “I want to make four self-contained feature-length films to be directed by different people and have different people involved in the key areas in terms of the unifying elements.” (Pictured above: Tim Roth with Eric Richard as Harry the social worker.)

So I went away and did research and thought about it. I wanted to find out more about social services so I befriended a social worker called Harry who then, during the course of my research and also while I was writing, took me everywhere. He took me to places where I wasn’t allowed to go really – juvenile courts, lock-ups, secure units and all of that and whenever we walked in, he’d just say, “This is David, he’s a trainee,” and as soon as he said that, I became the invisible man because nobody is interested in a trainee. Eventually I went back to Margaret and said, “I want to make four self-contained feature-length films to be directed by different people and have different people involved in the key areas in terms of the unifying elements.” (Pictured above: Tim Roth with Eric Richard as Harry the social worker.)

Why did you want to use different directors?

It was important to me that each film should have an individual feel. So we sat down and talked about what these films could be. I had already decided that there should be a film set inside a school that dealt with how children are taught, what they are taught and raising – and this was extremely important to me - the whole question of what physical punishment has to do with the process of learning and how the ethos of the school contributes to the general process of learning. That’s still extremely relevant today. So that was Birth of a Nation.

The companion piece to that was Flying into the Wind, about a family who choose not to send their children to school, which challenges the whole meaning and interpretation of the Education Act. The appeal in the Crown Court which you see in the film is very similar to what happened to the real family. When their appeal took place, I used to travel to Hereford Crown Court with their barrister Tony – Anthony Gifford – who had a reputation for taking on worthy causes and I got a lot of insight into his legal thinking behind it. I had transcripts of previous court appearances, a whole shed-load of stuff relating to the case – letters and so on. I used to go to the court and sit in the gallery and watch what was going on and then one day someone said to me, it might have been Tony Gifford, “Come and sit on the floor, come and get closer,” so I went down onto the court level to watch. The mother was on the stand that day, she’d been in the dock for two or three days defending her family in the most extraordinary way. I got through the morning and went into the afternoon session but within an hour I suddenly didn’t feel well. I had to leave the court room and went into the toilet and I just broke down – I couldn’t handle it and I couldn’t go back in. I did eventually go back into the gallery again but I hadn’t realised the emotional impact of watching this family being wrung out in court, although they did survive - they won their appeal.

In Flying into the Wind the child isn’t taken away from his parents but he does have to go to school.

Yes, the child is sent back to school. I don’t think that happened in reality.

At the end of Flying into the Wind, you see the boy in his school assembly and he looks so lost.

Yes, I mean that was certainly my intention to show that the boy was confident and enquiring in his own environment where he was given a choice about what he learnt, which is not what happens when you go to school. You can choose your GCSEs but how you learn and what you learn and the whole process of learning is completely different from the boy being in a scenario where he meets the tramp and hears all his stories and then, later, he sees the tramp’s dead body being pulled out of the water. The father gives the boy the choice as to whether or not he should see the tramp's dead body but the boy chooses to stay and is very interested, asking the doctor lots of very difficult questions.

Actually, Flying into the Wind is the only one of the films that I was disappointed with. I hated the music. It was so turgid and I felt that in no way did it represent the original family – something uplifting, like Bach or Mozart, would have been much more suitable because they were so inspirational. The real mother was such a bright light but I felt that the interpretation of the mother in the film was of somebody sitting on the edge of a pit and about to fall in.

Do you think that was simply due to the direction?

Yes, frankly, I do. I did talk to the director [Edward Bennett] along with Margaret before he started and then he went away and made this film. I was nowhere near, except I do think I was quite instrumental in pushing for Graham Crowden (pictured right in Flying into the Wind) who was the wonderful exception in it. I thought Graham was fantastic. I knew Graham quite well, he was in Beloved Enemy, and I’d become pals with him. He called himself Dwarf - I thought he referred to himself as Dwarf to everybody - and he actually gave me a garden dwarf, which is still sitting in my garden now, and whenever he phoned me up he’d say, “Hello – it’s Dwarf.” I once asked him why everybody called him Dwarf and he said, “Oh no, it’s only how I refer to myself when I’m talking to you.” He was wonderful.

Yes, frankly, I do. I did talk to the director [Edward Bennett] along with Margaret before he started and then he went away and made this film. I was nowhere near, except I do think I was quite instrumental in pushing for Graham Crowden (pictured right in Flying into the Wind) who was the wonderful exception in it. I thought Graham was fantastic. I knew Graham quite well, he was in Beloved Enemy, and I’d become pals with him. He called himself Dwarf - I thought he referred to himself as Dwarf to everybody - and he actually gave me a garden dwarf, which is still sitting in my garden now, and whenever he phoned me up he’d say, “Hello – it’s Dwarf.” I once asked him why everybody called him Dwarf and he said, “Oh no, it’s only how I refer to myself when I’m talking to you.” He was wonderful.

But that must have been disappointing to have something you have written turn out so differently to how you originally perceived it?

When I started to write for television, I made several things with Alan Clarke and the process of writing and directing was always a hand-in-hand experience so, whatever we did, we always spent hours talking about it. When we were researching Beloved Enemy we went to interview a man in Geneva who had all these secret documents and so on, and Alan and I would just burn shoe leather just walking around and talking about how we wanted to make it - we’d talk through every single element.

So when it came to Made in Britain, we did the same thing. Alan said to me, “I can’t make the film, Dave, unless I know how I want to shoot it.” We were in a cutting room – I’m jumping about here – in Soho Square where he was cutting a documentary, and he said, “Come here, come here, I want to show you something,” and we went upstairs where Stephen Frears was cutting Walter [1982 television film directed by Frears, starring Ian McKellen] and he said, “Show David this sequence.”

Chris Menges [cinematographer and director] had shot Walter using a steadicam which was a very rare piece of technology back then – it had been used a little bit but it hadn’t really caught on at all but of course now it’s ubiquitous. What appealed to Alan was that Chris really liked shooting with what he called available light. When he walked into a location, a social centre or whatever it was, he would look around and see how the place was lit, so if there was overhead lighting, such as one might find in an office suite, he would enhance that lighting, make it brighter by putting in more powerful bulbs, fluorescent tubes or whatever, in order to boost the available light. The innovation of faster, more sensitive film stock also helped to make this happen. It created a very particular quality, almost anti-digital camera work. Everybody wants crystal clarity all the time but this had a real lived-in texture and depth to it.

Alan hadn’t been up for doing Made in Britain initially but I think it was Margaret Matheson who slowly brought his attention round to it and then he saw an exciting way to shoot it so eventually Alan said, “If I do this film, Made in Britain, then this is how I want to do it.” Alan kept asking me questions about the piece and about Trevor and what he was like. I described him as a restless kid, always on the move and Alan said, “Yeah, right, right,” – Alan always said “Yeah, right, right” - and he become very passionate about it. He insisted on having Chris Menges on board and when Chris came to read the script he said he would do Made in Britain but only if he could do RHINO as well, because he loved RHINO, which is shot very differently. (Pictured above: Deltha McLeod as Angela in RHINO.)

Alan kept asking me questions about the piece and about Trevor and what he was like. I described him as a restless kid, always on the move and Alan said, “Yeah, right, right,” – Alan always said “Yeah, right, right” - and he become very passionate about it. He insisted on having Chris Menges on board and when Chris came to read the script he said he would do Made in Britain but only if he could do RHINO as well, because he loved RHINO, which is shot very differently. (Pictured above: Deltha McLeod as Angela in RHINO.)

But Made in Britain has been a constant seller and I think it has a cult status, definitely. And it launched Tim Roth – no one had ever heard of Tim Roth until Made in Britain.

It must be very difficult casting young actors, because they don’t have a track record.

That’s right. I think that’s why Mike Newell did such a brilliant job with Birth of a Nation – because it’s an ensemble piece, Birth of a Nation, and Mike Newell is the greatest ensemble director we have in film. I know that a lot of film directors turned down Four Weddings and a Funeral [1994] before Newell took it up and what makes that film is not the central performances, it’s the ensemble acting.

I loved the girl [in Birth of a Nation] – I can’t remember the character’s name - who says to Jim Broadbent when he asks her a question, because he’s trying to make her think for herself, “I don’t know! It’s your job to tell us. You get it into our heads and we write it down on a bit of paper!” Fantastic! All the kids were brilliant.

When did you first come across Tim Roth?

Casting Tim was entirely up to Alan and the casting director. He’d done a bit [of acting] before but not much. Alan just said, “Well, I’ve got somebody to play Trevor, I’ll get you in to come and see them.” When I first saw Tim, it was at that same cutting room in Soho. He was sitting on a rather low sofa with his knees up around his chin but he didn’t have much to say at all and I said, “He looks great but you’ll have to cut his hair off.”

I’m sure Tim would deny this but whenever we went to the rehearsals, Tim would say, “Is Trevor based on a real person?” and I’d say, “Yeah, yeah,” and I guess to some degree he was because my pal Harry, the social worker, spent a lot of time trying to get a gang of skinheads and ne’er do wells, who frequented some kind of centre in Swiss Cottage, off glue and stop them from hanging around in the streets. He was just trying to change their direction in life and keep them out of court. And that’s where I got the idea of the young black kid that Trevor shares a room with and hangs out with. There were these skinheads [in Swiss Cottage] who were always ranting about niggers and making incredibly racist comments and there was also this young black kid who hung around with them and I said, “Hang on a minute, isn’t he black or do my eyes deceive me?” and they said, “Yeah, but that's - whatever he was called - he’s different.” It was such a wonderful contradiction.

But actually, there was a lot of me in Trevor. I was getting rid of a lot of anger in my system about what I went through in terms of education - or lack of it - because I was very much a square peg in a round hole. I hated school and I realised something, just a couple of days ago – the thing I’m working on at the moment is filming in Budapest, so on Tuesday I went to Budapest. I’ve always hated saying goodbye to my wife and going away and when I came back I said - quite without thinking about it - “You know, I hate going away because it’s like going to school.” And I thought, God, that’s it. That’s the feeling - it doesn’t matter where I’m going, even if I’m looking forward to being there, I still get that feeling you used to get on Sunday nights when you hadn’t done your homework.

Originally you filmed a different ending to Made in Britain.

That’s right. The original ending was that after Trevor has been beaten up in the police cell, he is taken to a Borstal with a very harsh regime and I described the scene as: “Trevor and other inmates are trench digging.” Now, if you come from the country, you know that trench digging is a way of digging a piece of open ground and the whole point about the scene was that as they’re digging the garden, Trevor is saying, “This is great! Look at us! This is going to make us incredibly fit! We’re going to be like brick shit houses by the time we get out of here!” He saw it as a way of training for the life to come. Look out! Trevor’s still alive and well and he’s going to go somewhere.

I wasn’t there when Alan was filming but when I saw the rushes there was this walled garden and all these lads, including Trevor, digging holes in the ground. And I said to Alan, “What are they doing?” and Alan said, “They’re digging a fucking trench Dave, what do you think they’re doing?” And I said, “They’re digging holes.” And he said, “Well, that’s a trench right?” and I said, “No! It looks like they’re trying to escape.” But that was the difference between David Leland who was brought up in the country and Alan Clarke who was brought up in Liverpool. I’d love to find the footage but I think there are stills about somewhere. (See above. More stills can be seen on the Tales Out of School DVD.)

I wasn’t there when Alan was filming but when I saw the rushes there was this walled garden and all these lads, including Trevor, digging holes in the ground. And I said to Alan, “What are they doing?” and Alan said, “They’re digging a fucking trench Dave, what do you think they’re doing?” And I said, “They’re digging holes.” And he said, “Well, that’s a trench right?” and I said, “No! It looks like they’re trying to escape.” But that was the difference between David Leland who was brought up in the country and Alan Clarke who was brought up in Liverpool. I’d love to find the footage but I think there are stills about somewhere. (See above. More stills can be seen on the Tales Out of School DVD.)

You said there was a lot of your own frustration and anger in Trevor – where did this come from?

I was brought up in a village five miles out of Cambridge, which is very much reflected in Flying into the Wind, and when I passed the 11-plus I assumed I would be going to Cambridge County School, which would been the logical place to go as it was only a bus ride away. However, my parents were told that there was no room in Cambridge and therefore I would have to go to Soham Grammar School. To get there in the morning I had to get a train to Ely, then change for a train to Soham and then on the way back in the evening I had to get a bus to Ely and then hang about at the station for up to an hour and a half to get another train just to go a few miles down the track. We used to go and hang about the Cathedral and by the time you got home, you didn’t want to do your homework. It was horrible. There were a couple of other boys in the same boat and we used to sit in the station waiting room doing our homework but the station porter used to come and chuck us out.

And the school was even worse. It reflected a lot of the whole authoritarian nature of the school in Birth of a Nation. It was a very rigid form of teaching, which I think is still reflected in some teaching institutions today. There was no element of enquiry. Whether you understood something or not, you just had to write it down and get it into your head and it was always under the threat of violence. The French teacher would look over your shoulder and slip his signet ring onto his knuckle. “What are you doing boy?” he’d ask and you’d be hit on the back of the head.

So learning and the fear of violence were linked in my mind although the irony is, of course, that I never got caned, although I saw boys who were much braver and rebellious than I was getting whacked around with shoes, slippers, kicked up the arse, clipped around the head - all of that stuff that went on in almost in every class. And I think, on reflection, that although I wasn’t dyslexic, my brain operated in a different way to those around me. My writing was virtually illegible, I couldn’t spell – I still can’t spell – so if I handed in a piece of written work the teacher would just throw it back at me and say, “I can’t read this boy, go away and write it again.”

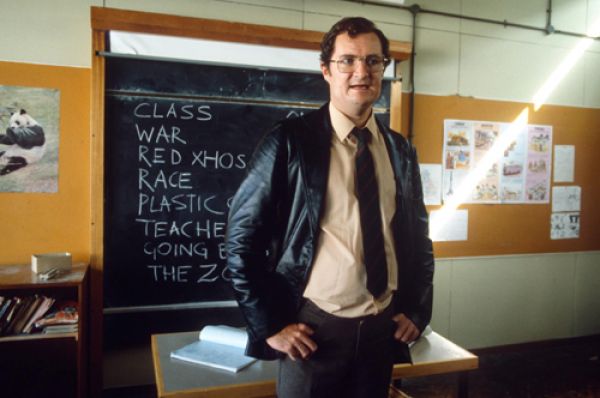

This all had a rather accumulative effect because I would always engineer to be unwell if there was a test coming up and as O levels loomed on the horizon, I spent more and more time making up illnesses and not being at school. At that time you could leave school at 15 so that’s what I did. I left school and, like my elder brother, went to work for my father who ran an electrical contracting business. I’ve never, ever talked about this before but talk about out of the frying pan into the fire because I hated that with a vengeance too. (Pictured above: Jim Broadbent in Birth of a Nation.)

This all had a rather accumulative effect because I would always engineer to be unwell if there was a test coming up and as O levels loomed on the horizon, I spent more and more time making up illnesses and not being at school. At that time you could leave school at 15 so that’s what I did. I left school and, like my elder brother, went to work for my father who ran an electrical contracting business. I’ve never, ever talked about this before but talk about out of the frying pan into the fire because I hated that with a vengeance too. (Pictured above: Jim Broadbent in Birth of a Nation.)

I was disastrously unhappy and I was looking for an escape. It took time but you must remember that we lived in a village and there is an invisible wall around any village – except now there is something called the internet which is a conduit to another world – but obviously at that time we didn’t have that. I think that for me, the biggest conduit out of the village was music.

There was jazz and then there was rock‘n’roll – Little Richard and Fats Domino. I really caught the jazz bug and was fortunate to be living near Cambridge because, thanks to the university, there were lots of jazz clubs. So I used to go to the jazz clubs – trad jazz clubs in particular, but also modern jazz clubs and there was also skiffle. I learnt to play the banjo and eventually I began to play with bands in Cambridge and I met a lot of arts students – my best pal was a clarinettist and he and his girlfriend were both art students – and then it dawned on me, “This is where I should have been heading. These are the people I want to be with.” At that time there were people like Peter Fluck and Roger Law, who went on to create Spitting Image, at Cambridge Art School, and used to organise anti-war demonstrations and, just as I was a truant from school, I became a truant from working for my father. Looking back, my parents were wonderfully tolerant.

As I’d left school with no qualifications at all, I was searching for something that I could do that didn’t involve qualifications. I couldn’t go to art school because you had to have an O or A level in art but I discovered that you didn’t need any dreaded qualifications to go to college to study to become an actor and I thought, yes! There we go! I was born to be an actor!

So I started to act. I was introduced to the head of English at Cambridge Tech who was always putting on productions and although I wasn’t a student at that time, I appeared in a production of Romeo and Juliet. Another man there who taught me English, started to tutor me for auditions and I met the county head of drama, a wonderful woman called Enid Barr who really was my fairy godmother. She said, “If you want to be an actor, then you have to get into a drama school and you have to get a grant,” – because I didn’t have any money and my parents weren’t going to pay either. So I went to see Enid several times and each time I went to see her she’d sit and talk to me for an hour and at the end she’d say, “Oh, acting’s a tough profession, you’d never survive. It would be awful. Go away and come back in a month if you’re still interested.” So I kept going back and going back and in the end she looked me in the eye and said, “Right, I’m going to help you,” and she did. She got me into acting in university productions and she used to include me in her county productions so I started acting more and more.

I auditioned for a drama school in Birmingham which was all a bit like reading Chekhov on the lawn so I wasn’t too keen on that, although they did offer me a place. Then I auditioned for the Central School of Speech and Drama in Swiss Cottage and I got in. When I eventually went to the town hall in Cambridge to be interviewed about a grant, and this line of people – the committee - talked to me, they said, “Ah, yes, we saw you in that Dylan Thomas play Return Journey, and you were very good.” It turned out that Enid Barr had engineered for every one of them to see me act. She had set the whole thing up and I got my grant.

The irony was that I lost it for a while, for a year in fact, because at Central, there was a wonderful teacher called John Blatchley - and also Yat Malmgren and Christopher Fettes - and they were very radical. Their teaching was exactly what I wanted, what I had never had in terms of my conventional education, but they were in a very conservative organisation and they clashed – it really was an old school/new school clash and at the end of my first year they were fired, and about 75-80 per cent of the students, including me, left with them to start a new drama school which was the Drama Centre.

But why did you start to write?

I think the writing started during the time I was training to be an actor. We were taught what was known as the Laban Carpenter psychology of movement, theory of movement. It had a language, a jargon attached to it, and we were encouraged to write scenarios – Al Pacino talks about this - which would give you a sensation of how other people behave. We would write scenarios and then perform them to each other and writing became a kind of secret obsession.

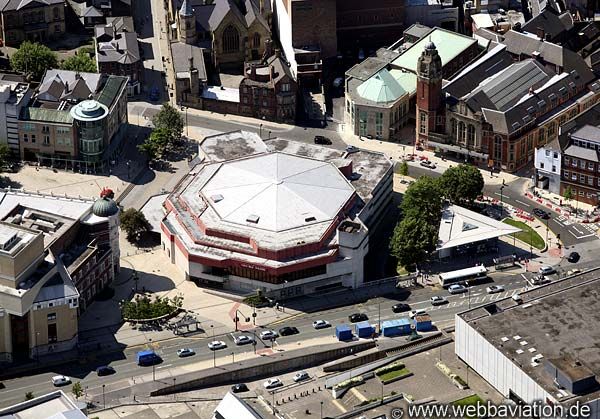

So I was always writing scenarios and ideas that I had for little plays but it wasn’t until I worked as an actor in a production of a David Cregan play called King with an actor called Peter James that I started to take it further. Peter lived near me in north London and we used to travel into rehearsals together. He told me was going to take over this new theatre in Sheffield, The Crucible (pictured above), and I told him about a couple of plays, mad plays, that a friend of mine had put on in New York and eventually he said, “Well, why don’t you come up to The Crucible and direct some plays and help me run the theatre?” And I thought, wow, what an amazing thing to do, because The Crucible was like the Starship Enterprise, dropped into the middle of an industrial city, this fantastic 1200-seater auditorium with a beautiful studio theatre.

So I was always writing scenarios and ideas that I had for little plays but it wasn’t until I worked as an actor in a production of a David Cregan play called King with an actor called Peter James that I started to take it further. Peter lived near me in north London and we used to travel into rehearsals together. He told me was going to take over this new theatre in Sheffield, The Crucible (pictured above), and I told him about a couple of plays, mad plays, that a friend of mine had put on in New York and eventually he said, “Well, why don’t you come up to The Crucible and direct some plays and help me run the theatre?” And I thought, wow, what an amazing thing to do, because The Crucible was like the Starship Enterprise, dropped into the middle of an industrial city, this fantastic 1200-seater auditorium with a beautiful studio theatre.

So that’s what I did. I never did get the rights to the plays that I’d told Peter about but I started directing other stuff, although I wasn’t particularly interested in putting on the classics, Rattigan and Wilde and so on. I put on a production in the main house called The Bomb in Brewery Street, written by Keith Dewhurst, which was about soldiers in Northern Ireland and that gave me the buzz to get more new plays and during the time I was there I put on two consecutive seasons of new work in the studio theatre. The first season consisted of seven world premieres that ran in repertoire, with a company that included Jim Broadbent, who was then a raw young actor, in a Clive Barker play. The following year I did a series of nine world premieres including a musical written by someone known as Victoria Wood – Talent.

I was first introduced to Vic by Ron Hutchinson [Northern Irish playwright]. I’d produced and directed a play by Ron Hutchinson, Says, I Says He, about two Northern Irish navvies that get hooked up with the IRA, which was a big success and transferred to the Royal Court. Ron had also written sketches for a little review show at The Bush [Theatre] and I met Vic one night with Ron and just as she was leaving I said, “If you’ve got any ideas you’d like to do, let me know.” She literally wrote the plot of this musical, Talent, on the back on an envelope and shoved it through my door and I said, “Right, you’re on. We’ve got to have this number of characters, you’ve got to perform and you’ve got to play the piano and I want it by such and such a date,” and she said, “Right,” and went away and delivered it bang on the dot.

However, in that season I had also wanted to get Ron Hutchinson to write a play about psychologists who work for the military. I’d read a lot about this over the years, having become very interested in psychology and human science, and I was a little outraged – more than outraged – by the whole way in which psychologists became part of the whole military machine, be it designing how a gun feels and looks and the way in which soldiers hold it to how user-friendly it can be. I thought it was a perversion of the science and I talked to Peter James and said, “I’d love to do a play about this and I want Ron to write it but he won’t do it, he’s writing something else,” so Peter said, “Well, you write it.” I told him I didn’t have time to do any writing, I was producing a season of nine plays and directing most of them so Peter told me to take two weeks off. I thought I’d never be able to write a play in two weeks but actually it took me 10 days and it was too long. So that was a revelation and that was how it started. Much later, I did another production of it – it was called Psy-Warriors - at the Royal Court and I asked Alan [Clarke] to come and see it, but he didn’t so I sent him the script and I got a note - notes from Alan always seemed to be written virtually on toilet paper - and he said, “This is great,” and eventually we made it for the BBC. So that brings us into a full circle of me working with Alan, because he made Psy-Warriors and then I wrote the quartet [Tales Out of School].

Why did you decide Clarke was the person to make Psy-Warriors?

I first worked with Alan as an actor in a BBC Play of the Month production of The Love Girl and the Innocent by Solzhenitsyn, playing Nemov, the "Innocent" in the title. We got on well - actors loved working with him - and we stayed in touch. Though staying in touch with Alan meant there were long periods when one heard little or nothing from him.

Anyway, I directed an awful lot, in fact I worked non-stop for five years because I was at Sheffield for three years and then I went to the Royal Court. A lot of the stuff I was writing and directing at Sheffield transferred to London, to The Bush and the Royal Court and so on. Vic’s little musical went to the ICA in the middle of a freezing winter - West End theatres were closing down but we had people queuing round the block in sub-zero temperatures. Then I went to the Royal Court and by that time I’d worked for five years non-stop but I was still broke. I had no money and I collapsed with exhaustion and it was while I was recovering that I started writing seriously.

At that time to survive economically in the theatre you had to be commercially successful, which I hadn’t achieved, or you have to become an artistic director. The idea of running a theatre is never something that appealed to me and because of my experiences at The Crucible, I think I was already on a course to becoming a writer and director and I was always very attracted to film. In fact, as an actor, I was more interested in acting in movies or on the telly than I was working in the theatre. I loved working in film, I thought the whole atmosphere was great.

So how did you become involved in your first film, Mona Lisa?

I think Steve Woolley [producer of Mona Lisa] and Neil Jordan [director and co-writer] had seen Made in Britain. Neil sent me a third of a page outline which was Mona Lisa and at that time they were talking about Michael Caine playing it – well, it was a different character really, which later became Bob Hoskins’s part.

And how did you find co-writing?

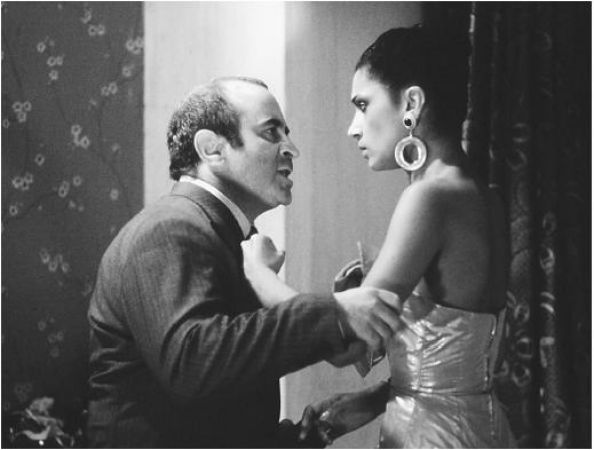

Well, I wrote – well, actually, I’m doing exactly the same thing with Neil Jordan right now. [More of which later]. I wrote a draft and gave it to Neil and Neil went away to rewrite it and he got two-thirds of the way through it and didn’t know how to end it - Neil always finds it hard to write the endings of films although I think he’s got better at it. So he gave it back to me and rather than me doing another version, we’d sit and talk about it. As we got closer and closer to shooting it, he’d taken a lot of stuff out of my draft and I think it lost its edge. (Pictured left: Bob Hoskins and Cathy Tyson in Mona Lisa.)

Well, I wrote – well, actually, I’m doing exactly the same thing with Neil Jordan right now. [More of which later]. I wrote a draft and gave it to Neil and Neil went away to rewrite it and he got two-thirds of the way through it and didn’t know how to end it - Neil always finds it hard to write the endings of films although I think he’s got better at it. So he gave it back to me and rather than me doing another version, we’d sit and talk about it. As we got closer and closer to shooting it, he’d taken a lot of stuff out of my draft and I think it lost its edge. (Pictured left: Bob Hoskins and Cathy Tyson in Mona Lisa.)

But on the whole it was a good experience because you’d written it together and you had the same vision?

Yes. I mean, I was perfectly happy because Mona Lisa was always Neil’s film. I’d been given very much an open canvas to write the way I saw it so I didn’t in anyway feel, oh, he’s changing my stuff. If it had been my original idea and I had written it – and this stays true to this day – if I come up with an idea, I want to write it my way, and then I will fight to keep my vision of the piece. Whereas with Mona Lisa I was happy to sit and listen to what Neil wanted to do – I’d argue with him, say he needed to do whatever, but it was Neil’s story. He is such a different writer and has such as different imagination. He gets ideas that come in out of the left field. When we were working on Mona Lisa he said, “Yeah, at this point, I think that the driver character, he should stop and go into a pet shop.” I said, “What?” “Yeah, he should go in there and buy a rabbit.”

And I went away thinking, why is he going on about rabbits? But it’s in the film. Bob Hoskins goes into the shop, buys a rabbit which he gives to Michael Caine, the gang boss, and at the end of the film, Michael Caine gets shot through the rabbit. But that was a very interesting lesson in a way, something that I learnt from Neil which is, if the producer says, “I don’t know why you’re doing that, it doesn’t make any sense at all” but it makes sense in your head and you can see how it will work on film, you should try to keep it in.

And then you made Personal Services and Wish You Were Here. I was in my agent’s – Jenny Casarotto’s – office one day talking to her about stuff and she said, “Look, you’ll have to go now, I’ve got Cynthia coming in,” and I said, “Cynthia who?” and she said, “Cynthia Payne,” and I said, “Who’s Cynthia Payne?” So Jenny told me about her [Payne ran a brothel in Streatham with some unusual clients, famed for accepting Luncheon Vouchers] and that they were talking about adapting a play from Paul Bailey’s biography, which I put under my coat and sneaked out, because I wasn’t supposed to have it. I was introduced to Cyntha in passing as I left the office and she immediately said, “Oh look, here’s a shy one – they’re always the worst.” And I thought, wonderful! This woman is a class act! So I read the book and talked to Margaret [Matheson] about it. Some time passed and when the idea of the play seemed to go into limbo, we decided to make a feature film of it. (Pictured above: Julie Walters in Personal Services.)

I was in my agent’s – Jenny Casarotto’s – office one day talking to her about stuff and she said, “Look, you’ll have to go now, I’ve got Cynthia coming in,” and I said, “Cynthia who?” and she said, “Cynthia Payne,” and I said, “Who’s Cynthia Payne?” So Jenny told me about her [Payne ran a brothel in Streatham with some unusual clients, famed for accepting Luncheon Vouchers] and that they were talking about adapting a play from Paul Bailey’s biography, which I put under my coat and sneaked out, because I wasn’t supposed to have it. I was introduced to Cyntha in passing as I left the office and she immediately said, “Oh look, here’s a shy one – they’re always the worst.” And I thought, wonderful! This woman is a class act! So I read the book and talked to Margaret [Matheson] about it. Some time passed and when the idea of the play seemed to go into limbo, we decided to make a feature film of it. (Pictured above: Julie Walters in Personal Services.)

Margaret went and saw Tim Bevan who was then running Working Title with Sarah Radclyffe and I started to write what became Personal Services. I began with, if you like the main character’s – Cynthia’s if you like - childhood because there was so much in there that interested me, but I got about 20 pages in and I gave it to Margaret and said, “So far I’ve got 20, 25 pages of this stuff and I’ve got a horrible feeling that by the time I get to her being a prostitute the film will have ended.” And Margaret read it and said, “You’re right – you’ll have to have another starting point,” so we started with Julie Walters [playing Christine Painter, the Cynthia Payne character] working in a café which is sometimes frequented by prostitutes.

I was fine with that but I still had ideas about what I wanted to do with what I’d already written so I went away and I wrote it really fast – once I’d got the initial material together, it took no more than about three and a bit weeks - and that became Wish You Were Here. And although a lot of the narrative comes out of Cynthia’s childhood, there’s also a heck of a lot that comes out of mine and what I remember from being brought up in a village. One of the most famous images from Wish You Were Here is of Emily Lloyd [playing Lynda Mansell, based on the young Payne] riding her bike with her skirt up yelling, “Up yer bum!” and in the village where I was brought up there was a girl about the same age called Eileen, who used to ride around the village green with the wind blowing her skirt up and all the boys would try and get a glimpse of her knickers. There was a lot of village life in there.

Then I put Wish You Were here on the shelf and carried on writing Personal Services. Tim [Bevan] was given the task of putting the film together, with help from Margaret, and looking for a director. It was great because Tim referred to me a lot. We’d discuss directors or certain actors we could get to play the parts to raise the money and there were times when I’d say, “Well, if you’re going to get that director, I might as well do it. I could do a better job of it than him!” But I think we were looking at a budget of about two and a half million and I’d never directed a film before so no one would back it at that price so in the end we decided on Terry Jones. Terry was a friend of mine and we discussed it and one thing we agreed on was that we shouldn’t co-direct it. He’d not enjoyed the experience of co-directing on Python and he wanted to get on with it himself but he did want me around because I knew the subject.

The first rehearsal for Personal Services was scenes with Julie’s character and her father in the film. Lots of questions came up and Terry would go, “Well David, what do you think?” and I would explain the background to it and at the end of the day Terry said to me, “You know, you know much more about this than me, why don’t you rehearse the actors and I’ll go and do my storyboard – I’m behind.” So although we had sworn at the beginning we wouldn’t co-direct, I did actually become a kind of invisible presence on the set. I worked a lot with the actors, particularly with Julie, and that worked terribly well although I have to say, there’s always - I think it’s better now - but at that time there were always slight misgivings about the presence of the writer on set. It was very strong in places like the BBC. When Alan and I did a Play for Today together and I was on the set more or less every day, some of the people on the production accused me of just turning up for a free lunch. And when you were queuing up for lunch they would say, “Get to the back of the queue, you don’t do real work." Horrible!

But Wish You Were Here did get made eventually.

After Personal Services Margaret brought in Sarah [Radclyffe from Working Title] to help us put a deal together for Wish You Were Here and one of the first places we took it to was Channel 4. David Rose [television producer, then a commissioning editor at Channel 4] knew my work in the theatre very well and was immediately supportive and very quick to say, “Of course, you must direct it, you should have directed a film long ago.” We had a budget of three-quarters of a million at that time, to shoot on 16mm and I brought in Ian Wilson, the cinematographer, who was a friend of mine, and we argued strongly that it should be shot on 35mm – feature material. Sarah managed to double the budget and we got one and a half million which gave us the money to shoot on 35mm. (Pictured above: Emily Lloyd in Wish You Were Here.)

After Personal Services Margaret brought in Sarah [Radclyffe from Working Title] to help us put a deal together for Wish You Were Here and one of the first places we took it to was Channel 4. David Rose [television producer, then a commissioning editor at Channel 4] knew my work in the theatre very well and was immediately supportive and very quick to say, “Of course, you must direct it, you should have directed a film long ago.” We had a budget of three-quarters of a million at that time, to shoot on 16mm and I brought in Ian Wilson, the cinematographer, who was a friend of mine, and we argued strongly that it should be shot on 35mm – feature material. Sarah managed to double the budget and we got one and a half million which gave us the money to shoot on 35mm. (Pictured above: Emily Lloyd in Wish You Were Here.)

By the time we got to Wish You Were Here, I’d really gone round the camera in practically every hat. I’d acted in front of cameras, I’d been on set as a writer, I’d directed in the theatre - and The Crucible is an arena theatre so you are directing in 360 degrees, like in film. It really was time for me to direct a film. I felt very comfortable and familiar on a set - I didn’t have any problems working out where I wanted to put the camera or how I wanted to do things.

Then I did The Big Man which came to me from Steve Woolley. He already had Liam [Neeson] and Joanne Whalley on board and he was keen to cast Billy Connolly, but the idea was that if Billy was going to do something, he wouldn’t have that Big Yin look - the beard and the wild hair. We didn’t want people to say, “Oh, look, there’s the Big Yin.” We wanted Billy to be there as an actor because he’s a very talented man. So, I went to meet Billy at his house and spent quite a long time with him and the major question I had in my back pocket - and I'd been told I had to ask him this – was “will you shave off your beard?” I didn’t mention this until the very end and then I said, “Of course, you know ideally we’d like you to…” and I hadn’t got the question out but I kind of had my hand on my chin and Billy said, “Aye! All off! All off! I’ll take it all off.”

It wasn’t mentioned again and then we started rehearsals and the producers would come in and say, “His manager says there’s no way he’ll shave off his beard,” and I said, “Well, he told me he would himself,” and they said, “Well, ask him again,” and I said, “I’m not going to ask him again. He’s already told me he will and I think he will shave it off.”

We were rehearsing in Glasgow and Billy used to fly back to London at the weekends and that weekend, he shaved his beard off for charity and when he came back on the Monday he was in quite a dour grumpy mood. I said, “What’s the matter, are you all right?” and he said, “No. I feel like the fucking invisible man. I came in this morning from the airport and nobody said hello. They were all looking at me like, ‘Who the fuck are you?’” Because nobody recognised him, which must have been very odd for him as everybody knows who Billy Connolly is. He’s a wonderfully warm human being. He just chats to everybody as if he’s known them all his life which is what makes him so successful because everybody in the audience thinks he’s talking directly to them. I thought he was fantastic playing the cowardly little fixer who was betraying his mother.

We had a lot of trouble with the Weinsteins [Harvey and Bob, co-founders of Miramax, the US production company] about the Scottish accent and Americans not understanding it. There was a long debate about a scene where Ian Bannen and Billy Connolly walk into a pub and Ian orders a double dram and a pint of heavy and the Americans said that no one would know what a pint of heavy was. We explained that it was a pint of beer but they insisted that no one would know what that was so we said, “Yeah, but the barman will pour a pint of beer and then he will put the beer upon the bar and therefore people will know that it's a pint of heavy.” And they argued for weeks about it - it would go on and on and on like that. We did manage to keep the pint of heavy in it but I’m disappointed with the ending of The Big Man - we wanted a much harder-edged ending which, again, the Americans wouldn’t agree to - although a lot of people have told me they like it.

Apart from the ending though, I think the film works really well, particularly the fight scenes. Liam rehearsed that bare-knuckle fight for weeks – there was a point whereby they [Neeson and Rab Affleck] could hit each other - their warm up was to hit each other but pull the punches at the last minute. We had amazing friendships with the boys from the boxing club in a boarded-up school on the outskirts of Glasgow. (Pictured above: Neeson and Affleck.)

Apart from the ending though, I think the film works really well, particularly the fight scenes. Liam rehearsed that bare-knuckle fight for weeks – there was a point whereby they [Neeson and Rab Affleck] could hit each other - their warm up was to hit each other but pull the punches at the last minute. We had amazing friendships with the boys from the boxing club in a boarded-up school on the outskirts of Glasgow. (Pictured above: Neeson and Affleck.)

And then there were about six years when you were commissioned to write scripts but nothing got made. How did that feel?

It swallows you up really. I was writing all manner of stuff for American studios, and earning a very good living doing so, and it took a long time to realise that it [having scripts produced] doesn’t have anything to do with the quality of what you’re writing. It’s all down to the package they can put together – what actors you can get and so on - and that determines what is made, even if the script is crap.

During that time I worked with and became friendly with JG Ballard, Jim Ballard. I was writing a script based on a novella of his called Running Wild, which never did get made, although we got incredibly near. Jim always said he had sold the film rights to most of his books but only two films had been made [Empire of the Sun (1987) and Crash (1996)] - he called it his pension.

And you also started making rock videos.

After Wish You Were Here, I made a film called Checking Out in America which was produced by Handmade Films, George Harrison’s film company. I became very friendly with George Harrison and George used to come and hang out on the set. He was in the process of trying to put a group together to make records with musicians he liked - Tom Petty, Roy Orbison, Jeff Lynne, Jim Keltner and Bob Dylan - and they became the Travelling Wilburys and I did the music videos for the Travelling Wilburys. George and I were planning a film, we wanted to do a Travelling Wilburys film but it ran into all kinds of rock‘n’roll difficulties.

Such as?

Trying to get deals together with all the guys – who were all terrific. Roy Orbison was one of the most wonderful people I ever met, what a man. He used to say, [talks in soft American drawl] “Hey Dave, come and sit down. Let’s have a chat,” and he’d tell me all these amazing stories about Elvis Presley. But they were all fantastic. Just sitting in an empty room with Bob Dylan for 20 minutes is an experience. Once we only exchanged about five words at the end of which he said, “Nice talking to you Dave,” and another time we talked for an hour.

If the film had happened when we planned it, then poor Roy – well, he died right in the middle of what would have been our shoot. And a year to the day after George died, there was a concert at the Royal Albert Hall, called Concert for George, which I filmed and put together with some documentary footage, which I’d also shot, to make a film, also called Concert for George. I won a Grammy for that. I’m the first banjo player to win a Grammy.

And then you directed The Land Girls (1998).

Although I was brought up in the country I didn’t really discover the English landscape until I made The Land Girls. We went zigzagging around all of Devon and Somerset looking for a farm, a wartime farm, and that’s incredibly difficult because all the farms have modern outbuildings, big metal barns and so on, but in that time I travelled a lot and I just learnt to really love the English countryside. (Pictured above: Anna Friel, Rachel Weisz and Catherine McCormack in The Land Girls)

Although I was brought up in the country I didn’t really discover the English landscape until I made The Land Girls. We went zigzagging around all of Devon and Somerset looking for a farm, a wartime farm, and that’s incredibly difficult because all the farms have modern outbuildings, big metal barns and so on, but in that time I travelled a lot and I just learnt to really love the English countryside. (Pictured above: Anna Friel, Rachel Weisz and Catherine McCormack in The Land Girls)

You directed an episode of Band of Brothers. That must have been very different to your experiences of working in British television.

That was a gift. It was amazing, it really was. The whole set-up and the company that one was in and all the departments, the producers, the stuntmen, the veterans, the armourers, they were all the best. There was a tank battle and I said, “How many tanks will I be able to have for that sequence?” and I was taken to this huge, huge building, this hangar, and they said, “Here is every working tank in Europe – is that enough?” I rewrote the screenplay of the episode that I shot - two major drafts and lots of revisions - and changed it quite radically but not quite enough as far as the Writers Guild of America was concerned so I never got a [writing] credit for it and the writer, the actual original writer of the script won a Writer’s Guild of America Award for it.

Did that annoy you?

No, because I was well aware of the process. If the bones of the story remain the same then the chances are the credit will go to the original writer. But it annoyed me when I saw him at the Emmys - because I won an Emmy for directing that – because he knew exactly who I was and he cold-shouldered me and he could at least have bought me a beer. He could have said, “I owe you a beer,” and I’d have said, “Great, how are you doing?”

And then you were reunited with Tim Roth in Virgin Territory (2007)?

Which began as The Decameron, but we were reunited with Harvey [Weinstein] and again there were a lot of fights. One of their great diversion tactics when they don’t know what they’re going to do with a film is to start to argue about the title so it started as The Decameron but apparently the Americans wouldn’t understand that, they would think it’s a pizza. So I said, “What did the Americans think of Jurassic Park then?”

But that was the time I worked with the mighty Dino de Laurentiis [the legendary Italian film producer, responsible for around 500 films – Virgin Territory was to be his last]. He’d be on set every day saying, “Why you do this shot? Why you do this shot?" So I’d tell him I was putting the camera up on the hill for a big wide shot and he’d say, [puts on Italian accent] “Nah – do close-up.”

And so what are you doing now?

I have written a screenplay which is about the annual Oxford/Cambridge boxing contest, which is kind of on hold while we try and raise the money, and I’m the executive producer and show runner on a Showtime series called The Borgias - the first series is about to be screened on Sky Atlantic, although I had nothing to do with the first series. My link into it is Neil Jordan who wrote a screenplay for a film about the Borgias that didn’t get made and then he brought it back from the dead file to make a series, which was by far the best thing to do because there’s so much material.

So are you writing or directing any of it?

Half and half. It's 10 one-hour episodes and Neil’s written the first five and I’m currently trying to write the latter half. I’ve been on a bit of a crash course in terms of Renaissance history but I’m writing the third one now and it’s great. I will also direct the last two episodes and it’s all being shot in the Korda studios in Budapest. Meanwhile, whist I’m writing, as show runner I’m also acting as quality control – when new actors and directors come in, you have to brief them on what you want to achieve in terms of each episode and deal with questions and reactions from Showtime, so it’s a producing job but it’s very hands on. It’s a fantastic team. I’m very lucky – even if I do have to go away.

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

Add comment