Sergei Paradjanov: Retrospective for a Visionary | reviews, news & interviews

Sergei Paradjanov: Retrospective for a Visionary

Sergei Paradjanov: Retrospective for a Visionary

The eccentric view of a Soviet-era oddball genius

Soviet-era film director Sergei Paradjanov is a figure whose complicated biography has often overshadowed his innovative and distinctive cinematic style. The first full UK retrospective of his work at the British Film Institute on London's South Bank, marking the 20th anniversary of the director’s death, gives a chance to reassess the paradoxes of his heritage, and delight in a character whose rebellious passion for life and for artistic beauty brought him through some of the worst trials that the Soviet system could impose on an artist. Meanwhile, an exhibition of photographs by his long-term collaborator Yury Mechitov catches the last decade or so of Paradjanov’s life in his native city of Tbilisi, and shows the richly human face of so complex a personality.

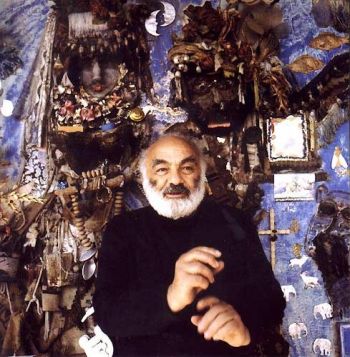

The name of Paradjanov (pictured right) cropped up sporadically in international film circles from the 1960s onwards. First came the struggles to screen his two early masterpieces, Shadows of Our Forgotten Ancestors (1964), and The Colour of Pomegranates from four years later, in the West; then, co-ordinated protest in the mid-Seventies against his imprisonment, that would eventually see the director released after four years into a gruelling five-year sentence; finally, his return to work with The Legend of the Suram Fortress (1984) and his final film Ashik Kerib (1988) two years before his death, and the renewed international exposure they received in the climate of perestroika.

The name of Paradjanov (pictured right) cropped up sporadically in international film circles from the 1960s onwards. First came the struggles to screen his two early masterpieces, Shadows of Our Forgotten Ancestors (1964), and The Colour of Pomegranates from four years later, in the West; then, co-ordinated protest in the mid-Seventies against his imprisonment, that would eventually see the director released after four years into a gruelling five-year sentence; finally, his return to work with The Legend of the Suram Fortress (1984) and his final film Ashik Kerib (1988) two years before his death, and the renewed international exposure they received in the climate of perestroika.

But despite the highest plaudits from other European masters, from the likes of Jean-Luc Godard (“In the temple of cinema, there are images, light and reality. Sergei Paradjanov was the master of that temple”), and his Italian contemporaries - from Fellini and Bertolucci to many others, who described him collectively on his death as a “magician” in cinema - his name has often remained somehow on the margins.

The format of the retrospective reveals one of the first paradoxes about Paradjanov’s work – namely, that he’d been making films for a decade before Shadows that simply bear no resemblance to those that made him famous. It’s not just a case of a director trying his hand in early works to reach a mature style, but of a categoric jump of change visible in everything, from narrative to aesthetic style. The London programme has four films from that earlier period, and it’s fair to say that the reason they’re rarely unloaded from their cans is that there’s little interesting there, other than as an unexpected foreword to what would come later.

That first decade of his career was Paradjanov’s Ukrainian period, given that he went to live there, and work at Kiev’s Dovzhenko studios, after graduation from Moscow’s VGIK film school in 1954. The strongest, Ukrainian Rhapsody from 1961, is a nice enough lyrical melodrama, telling a story that no doubt met Party standards, as did its aesthetic style, but with little more than that to justify disturbing the archival dust. Shadows (pictured below) had a simple narrative too, but a visual style that was entirely different.

The decisive jolt that was to change Paradjanov’s film-making for ever, as he himself acknowledged, was his exposure to his friend Andrei Tarkovsky’s first feature Ivan’s Childhood. “Tarkovsky, who was younger than I by ten years, was my teacher and mentor,” Paradjanov wrote. “He was the first, in Ivan’s Childhood, to use images of dreams and memories to present allegory and metaphor. Tarkovsky helped people decipher the poetic metaphor.” Composition, visual and musical effect would come to dominate over narrative, and the use of a local folk myth or national tale would be repeated in the director’s three remaining completed films.

The decisive jolt that was to change Paradjanov’s film-making for ever, as he himself acknowledged, was his exposure to his friend Andrei Tarkovsky’s first feature Ivan’s Childhood. “Tarkovsky, who was younger than I by ten years, was my teacher and mentor,” Paradjanov wrote. “He was the first, in Ivan’s Childhood, to use images of dreams and memories to present allegory and metaphor. Tarkovsky helped people decipher the poetic metaphor.” Composition, visual and musical effect would come to dominate over narrative, and the use of a local folk myth or national tale would be repeated in the director’s three remaining completed films.

Friendship with Tarkovsky was the strongest creative alliance in Paradjanov’s life, and he dedicated his final film Ashik Kerib to the younger director’s memory. Tarkovsky was one of those who protested most strongly, from within the USSR, against the director’s prison sentence, and their friendship survived Paradjanov’s wicked, often contrarian humour. Mechitov has a revealing anecdote from January 1982, where Paradjanov tells Tarkovsky that he is a “talented, very talented director, but not a genius,” to which Tarkovsky quizzically asked why that might be the case. “Because you are not homosexual, and have never been in prison,” came Paradjanov’s mischievous answer.

(Paradjanov’s own essential bisexuality was as complex as anything else in his life: his first criminal conviction, in 1948, was for homosexuality, while two years later he married a Tatar girl who was later killed by her family for abandoning her faith to do so. He married his second wife in Kiev, fathering a son and remaining on good terms with her after their eventual divorce through to the end of his life; nevertheless the procession of attractive youths, both in lead roles in his films and photographed by Mechitov as daily company, tells its own tale, albeit one left largely unspoken in a society where homosexuality remained illegal until 1992.)

The mere fact that such visual style had a life of its own - decadent or however else it might be described - and predominated over story, was enough in itself to put Paradjanov at odds with any official line. His manner of life, his sense of épatage directed at authority, and his inclination to explore “national” cultures – Pomegranates follows an Armenian story, Suram Fortress and Ashik Kerib Georgian and Azerbaijani ones respectively – also worked against the will of the centre.

Thus any release of his films in the Soviet Union itself was always limited, and his script proposals were repeatedly rejected in the early 1970s, but there must have been something more to Paradjanov that incurred the wrath of the authorities, and led to his arrest in 1973 on charges as wide-ranging (and questionable) as black-marketeering antiques, homosexuality and incitement to suicide.

The director was a thorn in the side of the authorities - much more so, it should be said, than Tarkovsky or another of their contemporaries, the Ukrainian Kira Muratova. Both would battle equally over scripts with Goskino, the central film administrative and funding structure. Mostly, those two were allowed to film, even if the final results never gained official approval and were left unreleased on the shelves until perestroika.

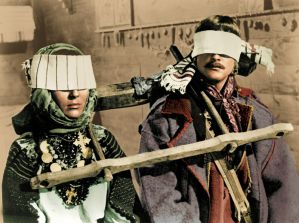

On his release from prison at the end of 1977 Paradjanov would live in Tbilisi until his death. (He would actually die in Yerevan in neighbouring Armenia, where the house that was being constructed as a place of creative refuge for him eventually became his dedicated museum, one which brilliantly catches the artist’s visual style and character, even though Paradjanov never actually lived there.) He had been born in Tbilisi in 1924, into an Armenian family, and increasingly became something an unofficial cultural patriarch of the Caucasus, at home in Armenia and Azerbaijan equally, with intelligentsia and ordinary people. His two last films touched sensitively on the cultures and worlds of both the region’s Christian and Islamic elements, in a region where such an approach would soon become the exception rather than the rule. Like Sayat, the multi-lingual Armenian troubadour hero of his Pomegranates (pictured), Paradjanov almost inadvertently became a “bridge between the various Caucasian peoples”.

On his release from prison at the end of 1977 Paradjanov would live in Tbilisi until his death. (He would actually die in Yerevan in neighbouring Armenia, where the house that was being constructed as a place of creative refuge for him eventually became his dedicated museum, one which brilliantly catches the artist’s visual style and character, even though Paradjanov never actually lived there.) He had been born in Tbilisi in 1924, into an Armenian family, and increasingly became something an unofficial cultural patriarch of the Caucasus, at home in Armenia and Azerbaijan equally, with intelligentsia and ordinary people. His two last films touched sensitively on the cultures and worlds of both the region’s Christian and Islamic elements, in a region where such an approach would soon become the exception rather than the rule. Like Sayat, the multi-lingual Armenian troubadour hero of his Pomegranates (pictured), Paradjanov almost inadvertently became a “bridge between the various Caucasian peoples”.

Mechitov’s Sergei Paradjanov: Chronicle of a Dialogue is a record of that final decade, the last not only in the director’s life, but also effectively of the old order itself: its final pages at the end of the 1980s see the beginnings of national unrest, and anticipate future struggles that would bring independence, but at a cost, both public and private, that would stain the decade that followed very dark indeed.

Chronicle of a Dialogue is a unique document of artistic collaboration over 13 years, one which began inadvertently but went on to assume the relation of master and disciple, subject and chronicler. It stretches to 460 pages, and catches Paradjanov in both private and public mode, in preparation for and shooting his last two features, and receiving the flow of guests that would gradually become a torrent (international presence came to include the likes of Marcello Mastroianni and Allen Ginsberg), all achieved despite the absence of a telephone in the building.

At a time in the early 1980s when American intellectuals were appealing to improve Paradjanov’s standards of living - reduced as he was, they wrote, to subsistence in his mother’s kitchen - the director was in fact lording over the whole picturesque courtyard which his apartment dominated, the large, open balcony of which hosted one long and hospitable feast after another. Though the majority of Mechitov’s pictures are in black and white, that sense of plenty, of belonging in a certain place and time that has now disappeared, is palpable.

The colour and richness in his great films that draw the viewer in, effective submergence in a highly visual and musical canvas - with images that often have a symmetry and sense of what Paradjanov called “motionlessness” - owe more to the East than to the West. He always resisted any critical judgment that termed his works only “national” films, downplaying what others would called their ethnographic elements, in favour of their universal quality.

In that sense they stand outside time. But one of Mechitov’s closing questions is this: to what extent did Paradjanov himself do so? Was it the Soviet regime in its then form that made him an artist – and did he in some way need it as the target of his subversion, his épatage? Had he lived longer, could he have created in the circumstances of the decade that followed his death? Equally, could he have created in the same manner had he been born elsewhere? Such questions remain open.

The final interview that Paradjanov gave was to Russian actor Alexander Kaidanovsky (himself the star of Tarkovsky’s Stalker). It will be screened for the first time in the UK as part of the festival, and watching it is a sad experience. The energy of the figure whom Mechitov likens to a human volcano, and the mischief and life of his face, has gone. The bitterness he feels about the 15 years he was “doomed” to inactivity for political reasons is palpable; the other rich strand of his artistic work, including collages made both from found objects and from Mechitov’s photographs, and decorative objects such as dolls which he went on making even while in prison, seem little more than “dreams of unmade films”.

As they discuss the three periods of Paradjanov’s past imprisonment, the director answers, “At present, I’m free,” as if some future political regime could once again become his captor. In reality, it was a very different opponent he was facing then – death.

- The Paradjanov Festival 2010 begins today at BFI Southbank and continues until 17 March. It includes a symposium, Shadows of Sergei Paradjanov, this Saturday 6 March.

- The festival continues at the Arnolfini in Bristol 1-23 April.

- The exhibition, Sergei Paradjanov through the Lens of Yury Mechitov, is at the National Theatre (Lyttleton Theatre foyer) until 28 March.

- Yury Mechitov’s Sergei Paradjanov: Chronicle of a Dialogue can be ordered from the festival organizers at info@glaz.co.uk

- Find the films of Sergei Paradjanov on Amazon.

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Film

Hot Milk review - a mother of a problem

Emma Mackey shines as a daughter drawn to the deep end of a family trauma

Hot Milk review - a mother of a problem

Emma Mackey shines as a daughter drawn to the deep end of a family trauma

The Shrouds review - he wouldn't let it lie

More from the gruesome internal affairs department of David Cronenberg

The Shrouds review - he wouldn't let it lie

More from the gruesome internal affairs department of David Cronenberg

Jurassic World Rebirth review - prehistoric franchise gets a new lease of life

Scarlett Johansson shines in roller-coaster dino-romp

Jurassic World Rebirth review - prehistoric franchise gets a new lease of life

Scarlett Johansson shines in roller-coaster dino-romp

theartsdesk Q&A: director Andreas Dresen on his anti-Nazi resistance drama 'From Hilde, with Love'

The East German-born filmmaker explains why his biopic of the activist Hilde Coppi isn't bound to the 1940s

theartsdesk Q&A: director Andreas Dresen on his anti-Nazi resistance drama 'From Hilde, with Love'

The East German-born filmmaker explains why his biopic of the activist Hilde Coppi isn't bound to the 1940s

Chicken Town review - sluggish rural comedy with few laughs (and one chicken)

A comedy great gets lost in an English backwater

Chicken Town review - sluggish rural comedy with few laughs (and one chicken)

A comedy great gets lost in an English backwater

F1: The Movie review - Brad Pitt rolls back the years as maverick racer Sonny Hayes

Joseph Kosinski's motorsport spectacle delivers bang for your buck

F1: The Movie review - Brad Pitt rolls back the years as maverick racer Sonny Hayes

Joseph Kosinski's motorsport spectacle delivers bang for your buck

Bleak landscapes and banjos: composer Bernard Hughes discusses his score for 'Chicken Town'

Our critic talks about his recent film project

Bleak landscapes and banjos: composer Bernard Hughes discusses his score for 'Chicken Town'

Our critic talks about his recent film project

28 Years Later review - an unsentimental, undead education

Allegorical mayhem in an eerily familiar zombie Britain

28 Years Later review - an unsentimental, undead education

Allegorical mayhem in an eerily familiar zombie Britain

Red Path review - the dead know everything

A compelling story of a trail of Tunisian tears

Red Path review - the dead know everything

A compelling story of a trail of Tunisian tears

Blu-ray: Darling

John Schlesinger's Sixties classic now feels problematic, but retains an icky fascination

Blu-ray: Darling

John Schlesinger's Sixties classic now feels problematic, but retains an icky fascination

Tornado review - samurai swordswoman takes Scotland by storm

East meets West meets North of the Border in a wintry 18th-century actioner

Tornado review - samurai swordswoman takes Scotland by storm

East meets West meets North of the Border in a wintry 18th-century actioner

Add comment