Sierra Pettengill has made the politest angry film I have seen. It has an incendiary quality that comes precisely from its calm stance towards its material. This is a polemic, but one that burns steadily under the surface and asks the viewer to take a measured approach to its material.

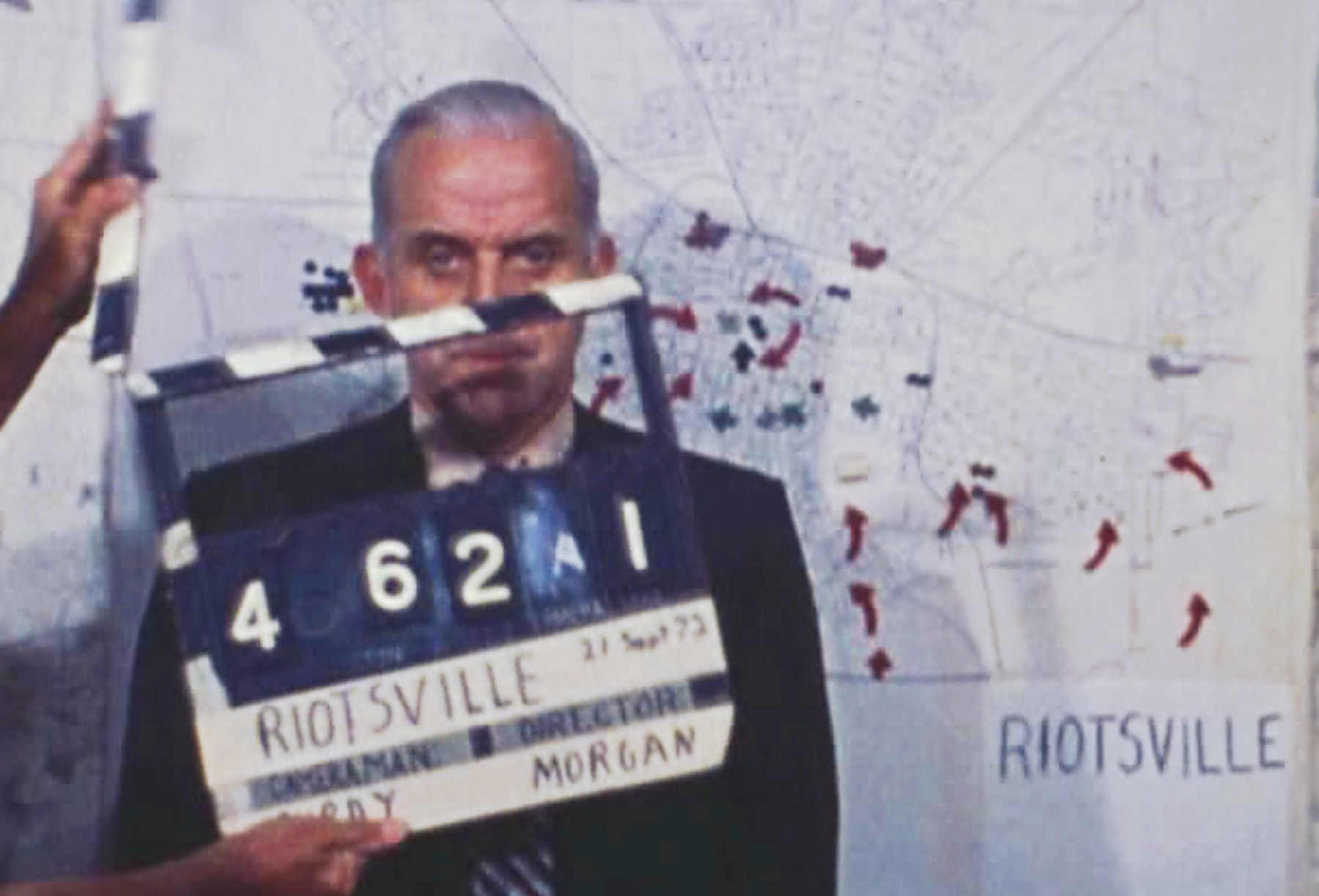

Fans of Adam Curtis documentaries will immediately recognise the unusual flavour of the archive material Pettengill has assembled in Riotsville USA: it reeks of its era of origin yet today seems surreal and other-worldly. She researched her material from 2015 to 2021 in multiple archives, including the US Government’s, and has patched it together into a story of Black suppression and revolt that began in the 1960s and has not ended yet.

But how to gain an impossible snapshot of a whole era, what the narrator calls a “pointillist picture of social collapse”? This gnomic voiceover drops in and out to suggest questions the footage is posing, but without heavily proscriptive answers. Instead we are invited to digest and assess. As do the professorial discussions about civil disorder we see on public service television of the time, many of whose panellists are black. All, except for a white police chief, keep a lid on their emotions. It’s a tough call when you see what the film has uncovered.

Its title comes from the nickname given to old military bases converted into training sites for civil disorder control. This initiative was a response by President Johnson to the riots in LA’s Watts district in 1965, Chicago in 1966 and Newark, Detroit and 100 other US cities in 1967. In a solemn TV address to the nation, we see him calling for a special advisory commission to attack the “conditions that breed despair”.

This was not a “political” move, he insisted. His implication, one we then see taken up by various law and order proponents, was that innocent communities were being stirred up by “outside agitators”, and covert operations were required to winkle them out. “Rhetorical alchemy,” the narrator calls it, “pain without politics”. The Vietnam war, she says, is never mentioned as a root cause of this angry disorder.

This was not a “political” move, he insisted. His implication, one we then see taken up by various law and order proponents, was that innocent communities were being stirred up by “outside agitators”, and covert operations were required to winkle them out. “Rhetorical alchemy,” the narrator calls it, “pain without politics”. The Vietnam war, she says, is never mentioned as a root cause of this angry disorder.

The commission was stocked with moderates, though nobody from the Black community. As for its “apolitical” status: LBJ was later reported to have threatened a commission member with castration by penknife if he forgot he was a “Johnson man” (an intentional LBJ witticism?).

The film begins with footage of a Main Street Anywhere, where civilians stroll peacefully. But then the camera zooms in on an army sniper on a rooftop, and you realise the buildings are about as real as a South Park backdrop. More soldiers march in, the temperature rises, the looting begins. This action is all being faked by extras at the first Riotsville site. Sitting in stadium stands nearby are senior members of the security services, watching the training of their personnel. As a bus leaves with Black “rioters" shouting out of the windows, they laugh and clap.

Trainees at Riotsville were taught to expect snipers and react accordingly, even though LBJ’s civil disorder commission found no evidence of agitators or even snipers at any of the riots. Only one item in the commission’s report was implemented: increased funding for the police. Its recommendations for correcting inequality in education, employment, welfare and all the ills LBJ sought to cure with his Great Society initiative, were ignored. Meanwhile, the US Army’s tear gas suppliers boosted their order books, riot control tanks became more heavily armoured, middle-aged white ladies started training to use handguns.

This story leads inexorably to the party conventions of 1968. The Democrats in Chicago were probably going to provide what the narrator calls “the TV event of the century”: Riotsville-trained police versus anti-war protestors, most of them white middle-class students. The networks hoped the visuals would bring the Vietnam war-machine to its knees. Instead, the public sided with the police.

The action then moves to Miami, and the Republican convention. When riot police arrived in a Black Miami neighbourhood, Liberty City, to control apparent disorder there, killing two women and a child by shooting randomly at residential buildings, the fakery at Riotsville had become real, and deadly. An intertitle pithily notes that the Miami police trained there.

That is typical of the understated way the film’s polemic develops. Its catalogue of tragedies does not thump you round the head, which inclines you to look at its findings coolly too. The voice-over (by Charlene Modeste, scripted by Tobi Haslett) is there to be digested and assessed. Editorialising is indirect: the song “Soldier Boy” mockingly plays over shots of Riotsville shooters; a hilarious promotion for Gulf bug spray fortuitously pops up in an ad break in NBC’s Miami convention coverage, suggesting pests can be destroyed with one strategic spray (agricultural insect sprayers were actually converted into tear gas sprayers in Liberty City).

One conclusion the film never overtly states is that the social impact of the Vietnam war was toxic. But it notes that LBJ ’s Great Society would have cost the same as waging a war; another reminder of spending priorities at the time is the rocket we see taking off (presumably in Florida).

As a closer, Pettengill goes back to the Harlem Riot, caused by the shooting of a Black teen by a white cop in 1964. It’s a sequence that links us directly to BLM and the present and seems to be her way of saying: stop oppressing Black people if you want proper law and order. Its found footage is startling and informative, but at times you yearn for the film to scream its message more obviously.

Add comment