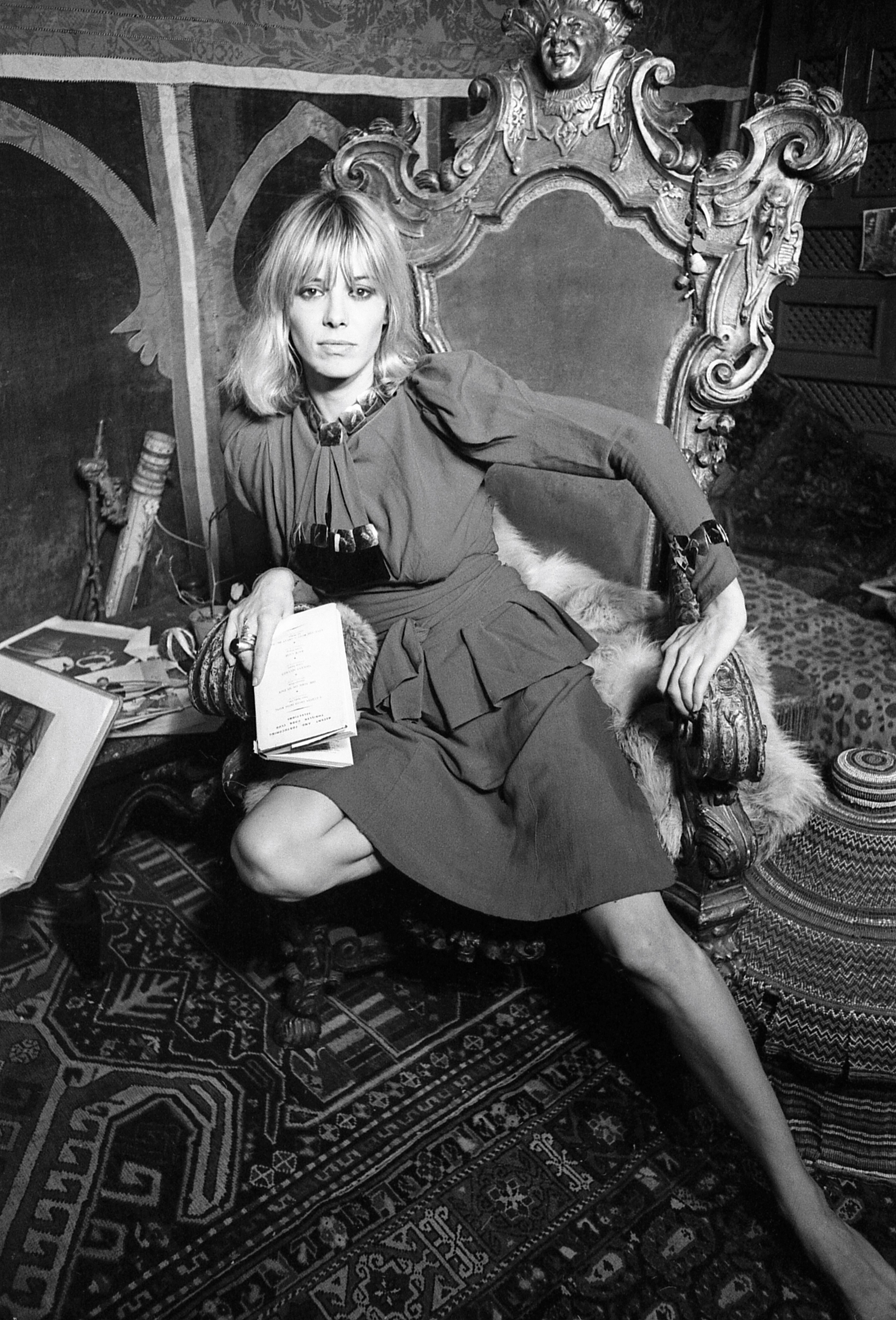

Anita Pallenberg was a vital presence in the Stones’ most vital years. Her bright eyes and hungry mouth betrayed a ferocious appetite for pleasure and adventure, taking her from a nun-schooled Rome childhood to New York’s downtown art crowd, then modelling in Munich, where in 1965 she engineered an encounter with “shy” Keith Richards, a similarly callow Mick Jagger and her first, violent Stones lover Brian Jones. Richards saved her from Jones’ paranoid abuse in 1967, and they became notorious outlaw lovers for the next decade.

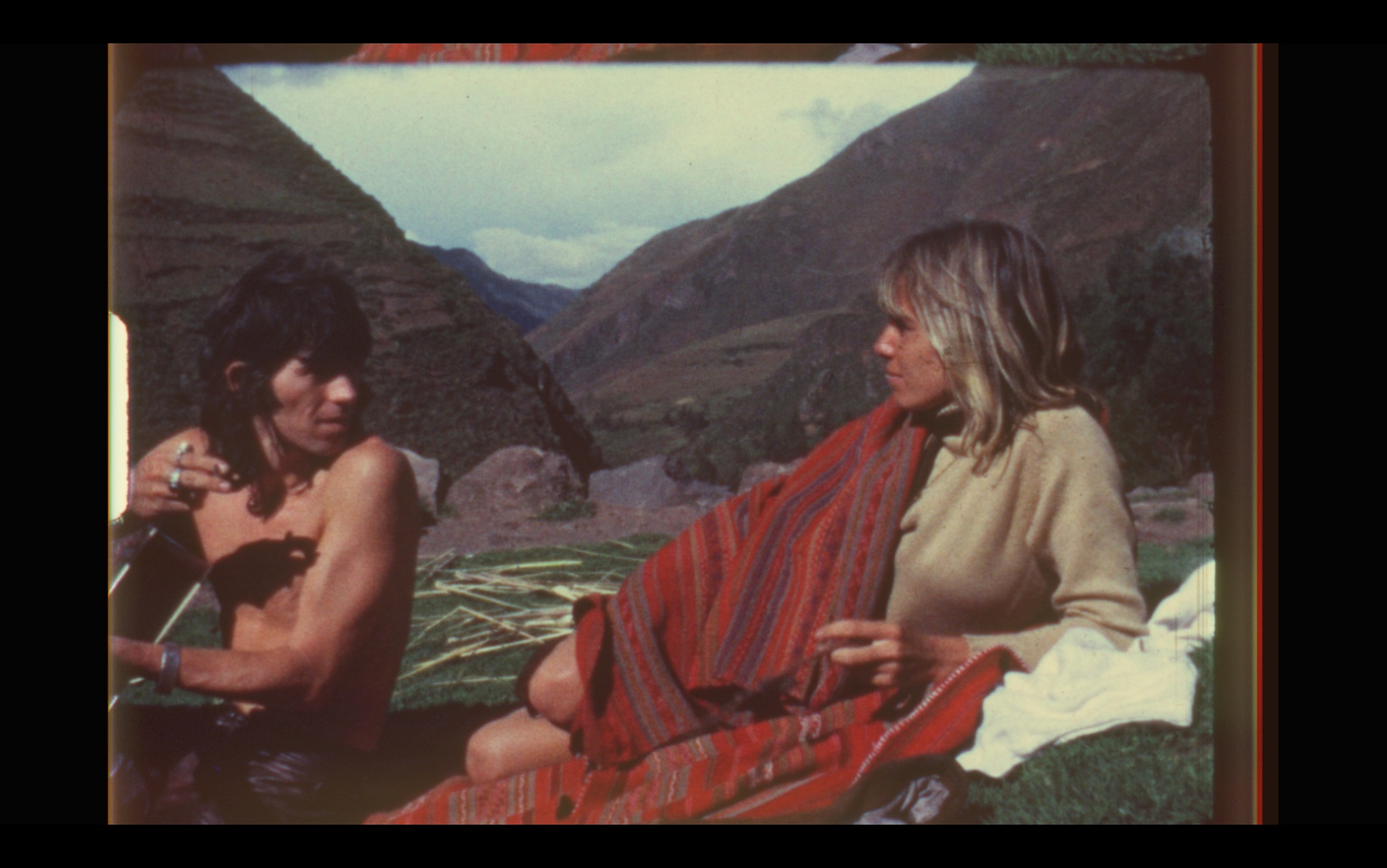

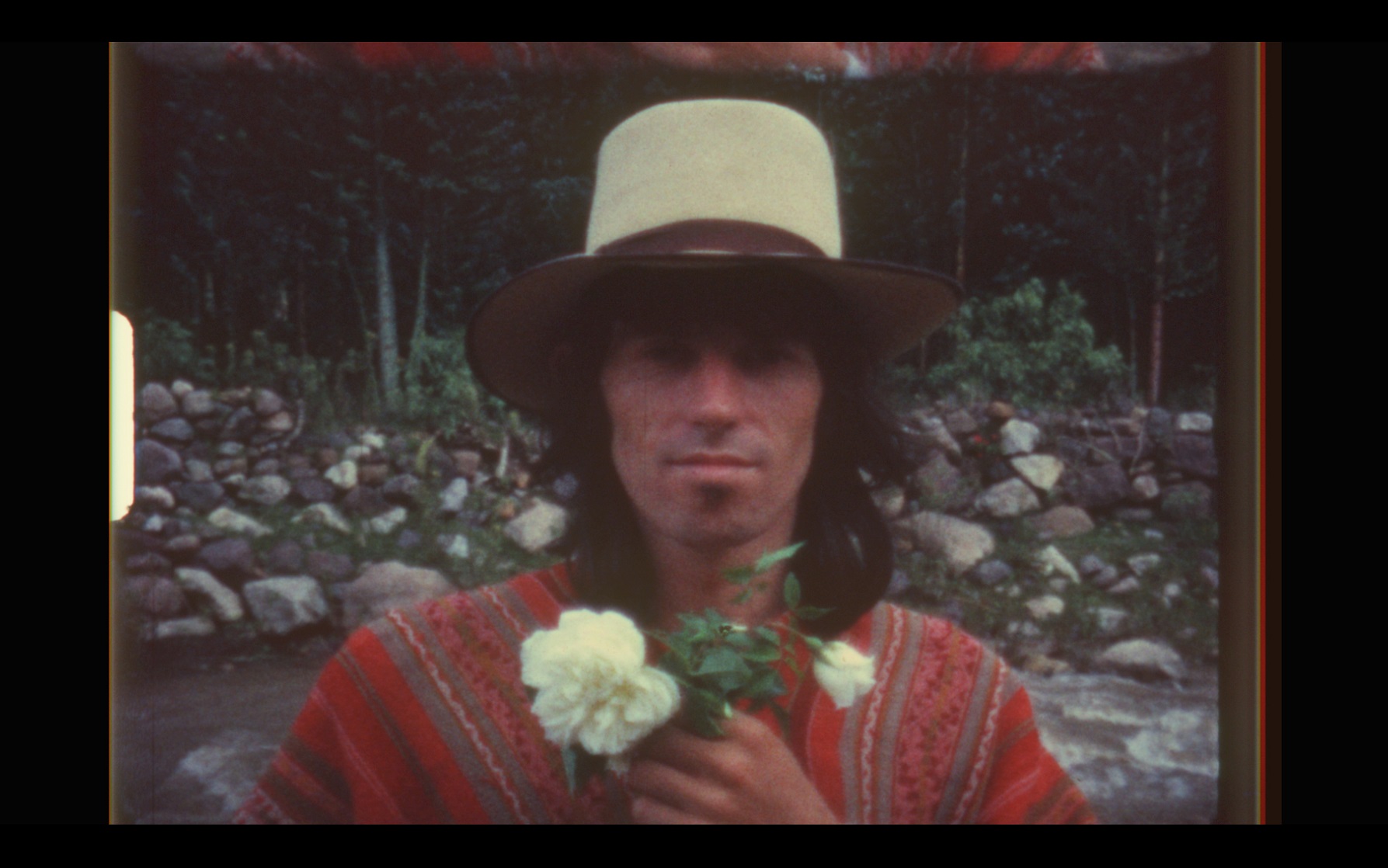

Co-directed by Svetlana Zill and Alexis Bloom, both associates of gimlet-eyed master documentarian Alex Gibney, Catching Fire: The Story of Anita Pallenberg is an immersive new film marshalling startlingly intimate home movies from the Sixties and Seventies – Anita and Keith preparing to shoot up or have sex, and in everyday life – alongside pages of recently discovered memoir narrated by Scarlett Johansson, and new interviews with witnesses to Pallenberg’s life including her two children with Keith, Marlon and Angela Richards. Marlon was also a hands-off executive producer, and vividly considers both chaotic, ultimately loving parents.

Pallenberg’s public image is both sultry and demonic, that of a sexy, smack-addicted hedonist who ultimately ruined her looks and life, prior to her death aged 75 in 2017. Catching Fire instead places her at the heart of the decadent, sometimes grim Stones life which resulted in songs such as “Sister Morphine”, “You Got the Silver”, “You Can’t Always Get What You Want” and “Angie”, all to various degrees inspired by her. Despite a cult cinema career, memorable as Barbarella’s Black Queen and Jagger’s lover in Performance, she didn’t pull free of the Stones’ story to make her own as Marianne Faithful did. She remained a muse, maybe stymied by female rock’n’roll life’s limits then. Refusing the passivity the term suggests, she was anyway a muse of mayhem.

Photos show Anita and Keith seem to physically merge, slim and slight in matching bohemian garb. “I was for a while considered one of the best-dressed men in the world,” Keith says in Catching Fire. “I was wearing Anita’s clothes.” His loving, generous interview is one of the film’s highlights, quite unlike his usual shtick. There was, he says, “a naturalness and vividness to how she operated, even in its most Machiavellian form”. Like Pallenberg, he has no regrets. “It was a total experiment, really…she made a man out of me!”

Photos show Anita and Keith seem to physically merge, slim and slight in matching bohemian garb. “I was for a while considered one of the best-dressed men in the world,” Keith says in Catching Fire. “I was wearing Anita’s clothes.” His loving, generous interview is one of the film’s highlights, quite unlike his usual shtick. There was, he says, “a naturalness and vividness to how she operated, even in its most Machiavellian form”. Like Pallenberg, he has no regrets. “It was a total experiment, really…she made a man out of me!”

“She was my myth…I wanted to be Anita,” a Rome schoolfriend similarly says, and photos from the Fifties and early Sixties show Pallenberg burning with her own blissful power. Perhaps this was her peak, derailed by the Stones’ voodoo, even as she cast her spells within it.

Pallenberg’s life fell into darkness marked by drug busts, addiction and death in the Seventies and Eighties, both catalyst and casualty of the band’s sometimes malign allure. Catching Fire shows her rehabbed and revived in later years, returning to cult films and the catwalk. It doesn’t dodge what might be called the collateral damage of bohemian lives, nor does it moralize in the current mode, neither romanticizing nor condemning a wilder, hard-boiled time when, as Keith bluntly said of Brian Jones’ death: “Not everybody makes it.”

“Moralizing films are less interesting, and people have had very varied reactions,” Alexis Bloom tells The Arts Desk. “Some have said, my God, ‘What a terrible mother.’ And some've said, ‘What a wonderful woman.’ Whatever you think of it, that was the way it was. And there by the grace of God go we.”

Svetlana Zill considers their film’s complex lessons, and Anita Pallenberg’s rich, darkling allure in the following conversation.

NICK HASTED: What did you learn from reading Anita’s unpublished memoir, Black Magic?

SVETLANA ZILL: It's by no means a comprehensive, unpublished memoir. There are several drafts and notes towards a memoir, and that's one of a few distinct attempts at writing about her life. You get a view into her interior world and her sense of humour, and it felt like a gift that we had her voice to tell the story. Marlon Richards was cleaning out Anita's flat in Chelsea after she died, and his kids ended up finding the manuscript pages. He knew he had all of that incredible Super 8 home movie footage from the Sixties and Seventies. And he felt like, between the footage and her words, this feels like a film. He felt the way that she left that writing behind was intentional, and it was his duty to tell his mother's story. He wrote this beautiful email to [co-director] Alexis [Bloom] about his love for his mother. He said, everyone knows about my father, Keith Richards, not many people know about my mother, and people need to know about my mother, because she was an incredible force of a human being.

Anita says writing helped her to “emerge in my own eyes”, which suggests that she even felt herself that she had effectively vanished into the Stones story, and was trying to reclaim herself from that.

I think it is an act of reclamation. The Stones have this all-encompassing fame that eclipses everything else in its orbit. I also think her emerging in her own right was related to her sobriety. She was able to become a fully realized person once she no longer had such heavy reliance on drugs and alcohol.

What does it say about her that she had this working life as a model, but she says she gave it up for acid?

What does it say about her that she had this working life as a model, but she says she gave it up for acid?

What do you think it says?

I guess the acid was really good then, for one thing. And she was a person of appetite.

She didn’t have some ambition or drive to be a model, but it was a good vehicle to make some money. She left home when a lot of young women didn't. And though she came from a relatively artistic background, her father wanted her to be a secretary at the family's travel agency. And she grew up in Rome. She was hanging out in Piazza de Popolo with the Fellini crowd. She definitely had appetites for travel and exploration and to follow her instincts. Especially in this day and age, there's this drive for success and fame and money in a way that wasn't her centre of gravity. It was seeking pleasure and experience, by way of drugs, but also by way of these other pursuits in acting and drawing and painting. And she was a very artistic person in that regard.

Volker Schlöndorff talks about watching her work as an actor on Barbarella, in comparison to Jane Fonda. She's a naturally interesting amateur, and I guess what she brings to her films is her life and experience.

I think that's true. In Barbarella, I think she loved playing the Black Queen and having everyone be terrified of her. But it's a conversation we had while making the film too, about how to present her in the context of her career, because it's not like she was some career-driven, ambitious woman. She had this drive and energy to just experience and take pleasure in the world.

So when Anita feels betrayed and depressed after Keith essentially put a lid on her going out to work as an actress, it’s not so much that she really missed the acting, it's that that life of experience is brought to a jolting, domesticated halt?

I think she was craving to be out in the world in that way. But she also loved being a mother, and she was adamant about wanting to be the one to raise the kids.

Does the film look into how a woman could be rock’n’roll then when not many women were playing the music - what a woman's role was in that energy?

I think of her as a proto-punk. She has this anarchist spirit, and this unique energy. She had that thing when she walks into a room and everyone is just drawn to her. Keith says she just wanted to kick it all over. It is the OG rock and roll energy.

The film takes the importance of the fashion and style that Anita gave the Stones seriously, and legitimates her role as a muse. What did her creativity give the Stones’ creativity?

I think they were terrified of her. It's so funny. I mean, Keith didn't even eat pasta. She brings this whole other European, sophisticated, cultured dimension. She's connecting them with different people from different parts of the world in this alchemical reaction. We tried to not be super-literal about, ‘She said this thing, And then this song got written.’ You can see the music that she inspires. In the times that she's really in the mix, there's some incredible music being made.

What were the most delicate areas of the film for the family?

What were the most delicate areas of the film for the family?

It wasn't as though there were some things so completely off limits. They lived through some hard times, but there's so much love in that family. And the North Star for the film was leading with love and tenderness. For all of the crazy trials and tribulations and tragedy that exists in the film - and there's other dark stuff that's not in it – there’s a deep love and respect that Marlon has for both of his parents, that they all have for each other, that Keith and Anita had for each other. There really was a deep love and a mutual respect there, that they remained close until she died. We only interviewed her family, closest friends and collaborators. But Anita demanded a kind of honesty from every relationship in her life. We didn't set out to do a hagiography. This is a woman who was complex, who was flawed, who was incredible in many ways, and also made some bad decisions along the way. And everyone felt a freedom to be brutally honest about her, because there's also so much love there, it's loving the whole person, not just celebrating the good times.

It reminds me of Nick Broomfield's film Marianne & Leonard: Words of Love [2019], about Leonard Cohen and his muse Marianne Ihlen, and the collateral damage of heedless, bohemian lives. That is in this film too, but it's not viewed through today’s judgmental prism, where excess is basically bad. This is a bohemian life that will naturally have casualties, and then the survivors just plow on.

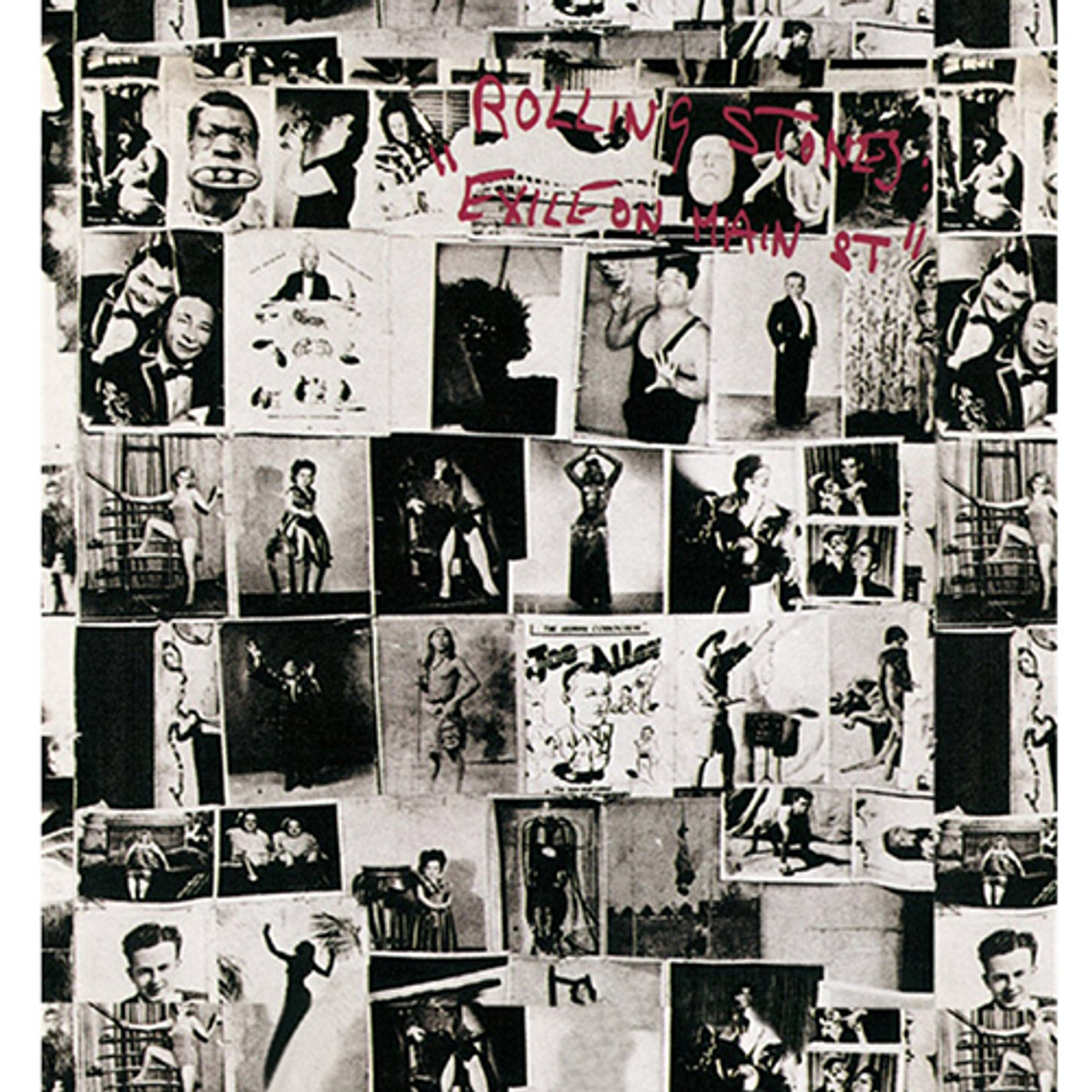

We were trying to have a tenderness, and an honesty about it, and not trying to have it through this lens of 2024, like, ‘Oh, you shouldn't…’ We included Jake Weber, the young boy at Nellcôte [Richards' French villa, where the Stones' Exile on Main St. was recorded in 1971] having his first bump of cocaine. He's a child when that happens. And it was something we struggled with in terms of, will we just completely lose the audience in 2023, because they've just written her off? Well, you know what? We have to take that risk because she did do that. And Jake jokes about it. It’s including some of that darkness because it was the reality. There's a version where it's full of judgment, and then there's a version that's just full of nostalgia. The reality is somewhere in the middle of all of that. And that's not necessarily a perspective that I feel like you hear, especially when it’s very easy to wax poetic about those Sixties.

What sense do you get of what Nellcôte meant to Anita? It seems just to have been exhausting, being the Bohemian mother cleaning up the mess - even when she was making some of the mess herself.

What sense do you get of what Nellcôte meant to Anita? It seems just to have been exhausting, being the Bohemian mother cleaning up the mess - even when she was making some of the mess herself.

I think you just said it perfectly. That is such a romantic period of rock and roll history. They're in this villa in the south of France, and Exile on Main St. is a genius album. There were some great parties that happened. But Anita's experience was not all rosy. There was the reality of, ‘We need to feed all these fucking people!’ and she's the only one who was multilingual, and it was on her to manage things [with Nellcôte’s international contingent] in that way. It's not like she's whining and complaining, but this is their life too. They have this young son, Marlon is three years old running around during this whole crazy time. He was too young to remember any of it, which is why it was so great that we got to talk to Jake, because he had that child's perspective. And he says that her and Keith were the co-alphas of the room. But there was a warmth and a tenderness to her, she really did look after [Jake] when he needed it most, when he lost his mother [socialite Susan “Puss” Coriat, who committed suicide in London in 1971, while her ex-husband Tommy was part of Keith and Anita’s Nellcôte entourage]. So even in that chaos and all of the drugs, there were these fun moments of joy [for Jake], just dancing and going for walks with Anita, doing very normal things that an adult's gonna try to cheer up a child who's just lost his mother.

The teenager Scott Cantrell shooting himself dead playing Russian roulette while with Anita in 1979 made me think back to a scene you show early on from Volker Schlöndorff’s film A Degree of Murder [1967], where Anita’s character takes the hands off the car’s wheel and says to the young men with her, ‘Let's see who's got the courage.’ It seems like by 1979, creative daring has descended into real life, where you're doing these stupid things.

I don't think that we know she challenged him in any way. I wouldn't make the direct parallel there, but there was a young boy playing with a gun and it's very dark.

After Scott Cantrell dying, she feels she must be this terrible person who's spreading death and destruction around her. But Marlon talks about her always marching forward. She wasn't dragged down by the things that happened, because she just left them behind.

You have all your note cards when you're editing a film, and it was forward, forward, that is her energy, that was her motto in some way. It is this need to drive forward, which I think is also generational, there was this post-war thing that she wanted to kick it all over. And eventually it came to a screeching halt, and then she had to reckon with it. There is a level of introspection later in life. But keep it moving is very much her vibe.

When you started watching the Super 8 films, what was it like to engage with that really deep intimacy? Some of it's stuff you wouldn't normally show outsiders. Some of it's intimate in the sense that it's just really ordinary, daily stuff.

It's the quotidian. Just happens to be famous people in the frame. Watching that footage, it's amazing. It's also at times infuriating. They're not cinematographers, and they're also incredibly high a lot of the time! So there's an energy to that too, it feels like you're in a world with them. If Anita's not in front of the camera, she's behind it shooting.

When you get down to that quotidian detail, then they stop being giants. The scale of the work remains, but they become human.

It's all very human. And I really enjoyed talking to Keith on that level too, because he's been happily married for decades now, he's had this whole other life and family, but Anita was family and was very important to him. And we were able to speak to him on a very human level about their relationship because he was the love of her life in many ways.

Usually when he's interviewed he is marvelous at spinning myths about the Stones, but there’s a different tone to his conversation with you. It's very personal and warm, and he's just trying to say nice things about the person he loved.

Usually when he's interviewed he is marvelous at spinning myths about the Stones, but there’s a different tone to his conversation with you. It's very personal and warm, and he's just trying to say nice things about the person he loved.

There was so much respect and a friendship that evolved, once they were no longer together. Anita was invited to family events, they spent Christmases together. We couldn't include it in the film, but we have this incredible footage of them later in life with Christmas hats. There's still so much love there.

It struck me that Anita as a girl and very young woman is her at full power. And it's like she got derailed by the Stones.

Seeing those photos of her even as a small child then as a teenager in Rome, there’s that dazzling smile and magnetism to her. If you're around fame you become known for, ‘She's the one with the Stones,’ or she's in Performance, or Barbarella. But you see 13-year-old Anita in pictures, and then you see 70-year-old Anita, and that is the same core person. There's an authenticity. She had that raw energy that's very much a part of her personality and of the times in the Sixties. People talk about her having so much energy that she would take drugs to keep it down. That it was this fire inside of her. And even as she's much older, in that smile, and the way her eyes light up, that energy is still there. It nearly got taken out by drugs and alcohol, but she triumphed over that and reclaimed that force.

Anita’s second act seems very significant to the sort of story she wanted to tell, to the extent that she wrote it down. There are tragedies within her story. But her story is not tragic.

We really try to calibrate it, to have so much darkness, and then to have it come around to this lighter thing. It's not like, all those crazy bad things happen and then she just quit drinking and everything is fine, there were struggles within that too. It's hard for people to reckon with that much tragedy and darkness and come out the other side of it. I think it was her spirit and her energy and strength that made that possible. Otherwise, she could have easily been another one of the casualties of that era’s hedonism. There are many people who we see in the film who were.

- Read more film features and reviews on theartsdesk

Add comment