Leaving Home, Coming Home: A Portrait of Robert Frank review - the artist puts himself in the frame | reviews, news & interviews

Leaving Home, Coming Home: A Portrait of Robert Frank review - the artist puts himself in the frame

Leaving Home, Coming Home: A Portrait of Robert Frank review - the artist puts himself in the frame

The reluctant subject who reveals his soul

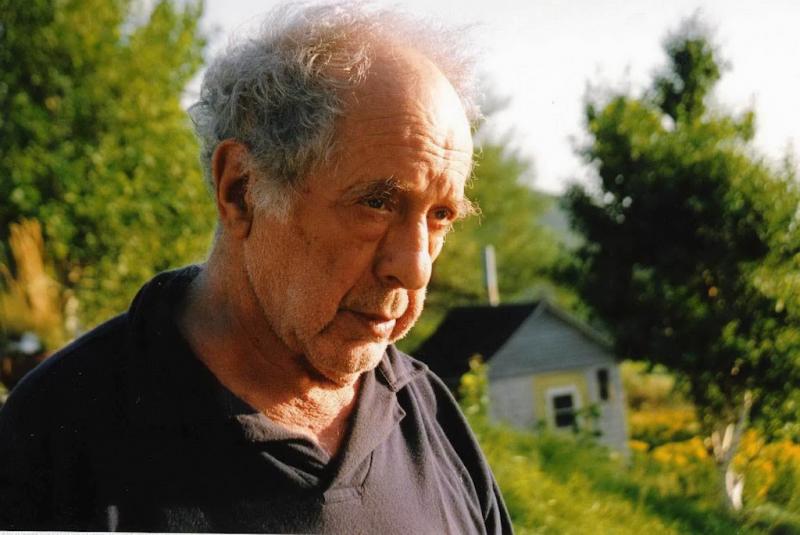

Shot in 2004 when photographer Robert Frank was 80 (main picture), this award-winning film was aired on The South Bank Show the following year, but is only now on release.

His patience is sorely tested when the camera runs out of film. Director Gerald Fox (notable for films on artists Gilbert & George, Marc Quinn and Bill Viola) asks him to repeat everything he has just said. “I can’t do this,” Frank protests. “I’m not an actor. This is bullshit ... We’d be better off going to Coney Island.”

And off they go. Frank brings along a photo he shot 60 years earlier and tries to locate the spot where it was taken. Cue photos of people sleeping on the beach during the night of 4 July, 1958. Lying prone under flimsy towels, they look more like corpses than revellers, partly because one associates black and white pictures with war photographs, but also because of Frank’s dispassionate eye. That eye had previously been used to brilliant effect when he came to London in 1951 and photographed people at either end of the class system (pictured below, "London 1951").

Published in 1958, his book The Americans held up an unflattering mirror to American society. No-one had seen photographs quite like them and they outraged critics. “There is no pity in his images”, wrote a disgruntled reviewer. “They are images of hate, hopelessness and desolation.” He was accused of being “a liar, perversely basking in the misery he is perpetually seeking.” But beat poet Jack Kerouac saw things differently. In the introduction he wrote that Frank “sucked a sad poem right out of America onto film, taking rank with the tragic poets of the world.” And the photographs are now world famous.

Frank recalls the police stopping him in Mississippi for giving a lift to “a nigger”. The experience, he says “made me feel more for photographing black people, and observing how elegant they were in comparison to the fat white people.” Whether recording the girl operating a lift in Miami Beach, the shoeshine boy stationed in a urinal in Memphis, Tennessee or assembly line workers at the Ford factory in Detroit, he clearly sympathises with the underdog. Yet he does not proselytise. “The pictures have to talk, not me”, he explains, but “if you have some brain and some feeling for people, you’re going to be a good photographer.”

Soon he was making films and these gradually become more autobiographical. Despite his reluctance to open up, Frank reveals the twin tragedies that have blighted his life. In 1974 his daughter Andrea was killed in a plane crash aged only 20 and, 20 years later, his son Pablo died at 44, having spent years in and out of mental hospitals.

After Andrea’s death, Frank began taking polaroids which he juxtaposes, annotates and reshoots as assemblages that are reminiscent of a family album or the storyboard for a film. It feels as if he were striving to discover meaning by plumbing the depths of what he describes as “the loneliness you feel if your child has gone, left alone with your memories and your thoughts.” Focusing inwards, this ongoing body of work seems poles apart from the outward-looking documentary photographs that made his name. Yet listening to him talk about them it becomes clear that, in different ways, both mirror his state of being.

After Andrea’s death, Frank began taking polaroids which he juxtaposes, annotates and reshoots as assemblages that are reminiscent of a family album or the storyboard for a film. It feels as if he were striving to discover meaning by plumbing the depths of what he describes as “the loneliness you feel if your child has gone, left alone with your memories and your thoughts.” Focusing inwards, this ongoing body of work seems poles apart from the outward-looking documentary photographs that made his name. Yet listening to him talk about them it becomes clear that, in different ways, both mirror his state of being.

The most enjoyable parts of this moving documentary show Frank with his second wife, the sculptor June Leaf – a wonderfully feisty woman who has sustained him throughout. We see them in the New York studio and in Mabou (pictured above), a remote spot in Novia Scotia where they have a house. Mutual love and respect shines through the banter.

“Robert is like a man with chopsticks”, says Leaf. ‘He watches and watches and then he takes the chopsticks and picks the most lasting, essential thing out of the chaos.” It is the best description of his photographs I have yet to come across.

- Leaving Home, Coming Home, A Portrait of Robert Frank opens at Curzon, Soho on 2 May

- More film reviews on theartsdesk

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

Add comment