Clive Davis: The Soundtrack of Our Lives, Netflix review - a friendly provocateur | reviews, news & interviews

Clive Davis: The Soundtrack of Our Lives, Netflix review - a friendly provocateur

Clive Davis: The Soundtrack of Our Lives, Netflix review - a friendly provocateur

The man who told Bruce Springsteen he hadn't written a hit single

Interviewed in isolation last week by Hollywood Reporter, music mogul Clive Davis revealed that he’s using his time “either by listening to the newest singles that make the charts or by watching hit music videos. First to be aware of them and then to keep my ears as current as they can be.”

Just turned 88 and sequestered in Palm Springs, Davis was missing his family. He’d been due at the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame induction ceremony and then at New York University’s Tisch School of Arts, where he himself was to be honoured. Both events were of course cancelled but he needs to be “prepared and educated”, a work ethic and musical curiosity that’s served him rather well, as the documentary Clive Davis: The Soundtrack of Our Lives reveals.

Based on Davis’ second memoir (the first, Clive: Inside the Record Business, written and published in 1975, quickly acquired almost legendary status), it's an extraordinary two-hour tale of a man with great ears and a passion to match who fell into a business he’d never even considered. Indeed, when Columbia plucked him from the small New York law firm where parent company CBS was a client, he at first turned down the offer – he’d been offered the role of head of the musical instruments division, which included Steinway and Fender. Instead, he accepted the position of assistant counsel for Columbia. Following moves and structural reorganisations, he became President of CBS Records in 1966.

The company was then preeminent in classical music, Broadway and MoR – bandleader Mitch Miller, the Colonel Sanders lookalike who was then head of Columbia A&R, thought rock “a passing phenomenon” and believed there were two kinds of music, "good and bad and the rest is all bullshit". So Columbia had a lot of catching up to do and Davis’s first signing, at the Monterey pop festival to which Lou Adler had invited him, was Janis Joplin. She suggested they mark the occasion by going to bed together – he replied that he didn’t mix business with pleasure!

“Dazzled” by what he’d seen at Monterey, Davis had soon signed Electric Flag, Blood Sweat and Tears, and Chicago. It was “titillating and nerve-wracking”. Bill Graham invited him to the Filmore West to see a new act – Santana. Another signing. Having discovered “a natural gift I never knew I had”, Davis believed he now had to stand or fall on instinct. Happily, that instinct served him very well indeed.

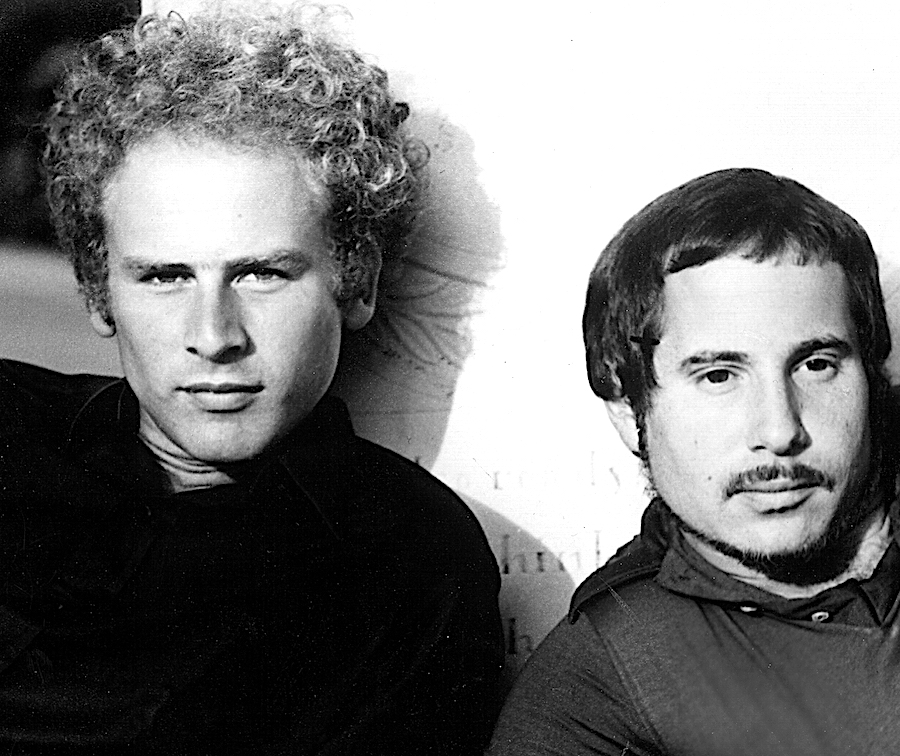

Paul Simon thought Davis “smart and friendly” but was taken aback to be told that the next Simon & Garfunkel single should be not “Cecilia”, his own choice, but “Bridge Over Troubled Water” (pictured left, Simon & Garfunkel). Bruce Springsteen was surprised to be informed that his debut album, Greetings from Asbury Park, NJ, did not contain a hit single – so he went to the beach and wrote “Blinded By the Light”. Miles Davis was told he should stop whingeing about white guys stealing his audience and put on some Indian threads and play the Filmore. As a result, Bitches Brew, a jazz-rock fusion, was quickly a bestseller.

Paul Simon thought Davis “smart and friendly” but was taken aback to be told that the next Simon & Garfunkel single should be not “Cecilia”, his own choice, but “Bridge Over Troubled Water” (pictured left, Simon & Garfunkel). Bruce Springsteen was surprised to be informed that his debut album, Greetings from Asbury Park, NJ, did not contain a hit single – so he went to the beach and wrote “Blinded By the Light”. Miles Davis was told he should stop whingeing about white guys stealing his audience and put on some Indian threads and play the Filmore. As a result, Bitches Brew, a jazz-rock fusion, was quickly a bestseller.

In 1973, Davis became the fall guy for a financial scam. Simon thought it “a shameful chapter in Columbia’s history” and Davis himself says that “it still hurts”. Two years later he founded Arista, where his signings included Barry Manilow, the Bay City Rollers, the Kinks, the Grateful Dead, Gil Scott-Heron (“in a major sense, the first rapper”), Patti Smith, (“the real thing”) and Lou Reed. He launched a country music division with Alan Jackson at a time when country was considered uncool. He looked for artists who had fallen from favour, notably Dionne Warwick, whose first Arista album went platinum. Aretha Franklin called him up. And in a New York City nightclub he heard 19-year-old Whitney Houston. Her debut quickly sold 22 million copies and she had seven consecutive number one singles. Her self-destruction broke Davis’ heart: he treated Whitney like a daughter and tried his best to help her, writing a letter in which he said he would stand by her “until you find peace”. He signed Puffy, who articulated an early version of hip-hop.

Pushed out of Arista by two BMG executives who were themselves later fired, Davis was quickly brought back into the fold for a $150m start-up, J Records. Eighteen Arista execs followed him. Signings included Alicia Keys, Luther Vandross and Rod Stewart, whose first Great American Songbook collection – dreamed up with a friend over a few bottles – had been turned down by everyone in town.

Davis is still at it, now Chief Creative Office of Sony Music Entertainment, owner of Columbia, which merged with BMG in 2004. An essentially family guy with a childlike love and enthusiasm for music and an insatiable desire that everyone he the best they can be, he sees himself as “your friendly provocateur” who believes that “you have to keep reinventing yourself”. His career proves you can have taste and make money. Respect, man, respect.

rating

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

Add comment