DVD: Oscar Peterson - Black + White | reviews, news & interviews

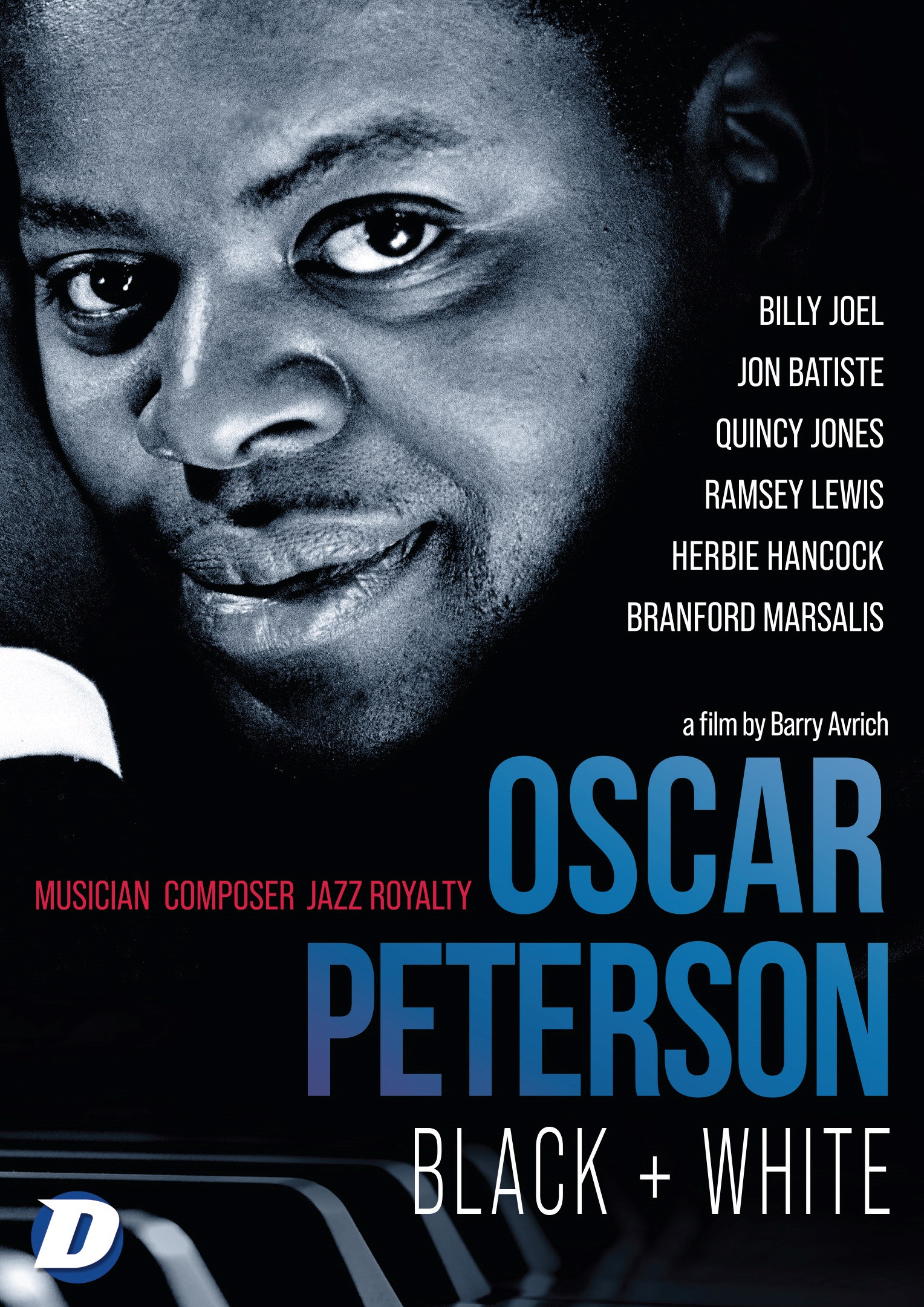

DVD: Oscar Peterson - Black + White

DVD: Oscar Peterson - Black + White

Barry Avrich’s documentary celebrates the music and career of the great jazz pianist

I can’t help enjoying the continuing elevation of the jazz pianist Oscar Peterson (1925-2007) to national monument status in Canada. A park or a square here (Montreal), a boulevard there (Mississauga), a school, a concert hall, a statue, a commemorative one-dollar coin. Now Barry Avrich’s 2021 documentary Oscar Peterson: Black + White, which is being released on DVD.

It tells Peterson's story well. A wide range of archival footage, notably several interviews with the pianist, has been trawled, carefully assembled, and juxtaposed with new interviews and specially commissioned performances, all woven into a satisfying narrative.

The roll-call of people assembled to praise Peterson is impressive. There is an all too brief cameo with Clint Eastwood and Ray Charles, no less, seated together at a piano. They smile. They nod in agreement: “Yes, Oscar can play.” And that’s it.

There’s Quincy Jones (“Oscar was the greatest there ever was”), Billy Joel, Branford Marsalis, Ramsey Lewis, plus a lot of thoughtful analysis from the New York Times’s Giovanni Russonello. His two-word formulation to describe Peterson’s playing – “powerful warmth” – says a lot.

Herbie Hancock responds to the question of the right place to situate Peterson in the panoply of jazz piano players with: “He’s at the top of the heap.” Later on, filmed at a tribute concert, Hancock says, “I owe him everything and he is irreplaceable.”

Herbie Hancock responds to the question of the right place to situate Peterson in the panoply of jazz piano players with: “He’s at the top of the heap.” Later on, filmed at a tribute concert, Hancock says, “I owe him everything and he is irreplaceable.”

The story of Peterson’s life has been well-covered in books like Gene Lees’ 1990 biography The Will to Swing, but the medium of film has clear advantages, not least the scope to let Peterson’s music set the mood.

The most sustained example of this is a 10-minute section about segregation and the human rights movement. The music for it is confined to one tune: "Hymn to Freedom”. Classic footage of Peterson’s trio with Ray Brown and Ed Thigpen playing it in Copenhagen in 1964 has been spliced with a new recording of the tune made specially for the film.

In fact, we lose sense of whether we're hearing the 1960s version or the new recording. That fits very cleverly with the footage we're seeing: the juxtaposing of images of Martin Luther King, Barack Obama, and the George Floyd protests emphasises the parallels between "then" and "now". The slow pulse of “Hymn” is the constant that holds the section together. The music makes the point that the struggle is ongoing.

This section is also a strong reminder of the involvement in Peterson’s career of the producer and impresario Norman Granz (1918-2001). His mission was to use jazz as a vehicle to promote social justice. The footage of Granz reveals what a persuasive and era-shaping advocate he was, and also how completely determining his role was in managing Peterson and guiding his career.

In another striking section, Peterson tells a story from his youth about how he first heard the playing of Art Tatum. Interviewed on TV by André Previn, Peterson says that when he first heard Tatum it led to him having crying fits at night. But the long-term effect was the opposite: if there was one pianist who took Tatum’s legacy forward it was Peterson. As he told Previn, the experience galvanised him in his determination to "frighten the hell out of everybody pianistically.”

The Canadian musicians who have been commissioned to play Peterson’s music are uniformly excellent – perhaps the sheer quality of jazz players in Canada is one of the best-hidden secrets anywhere. Drummer Larnell Lewis is exceptional, as is a quiet and unassuming but special guitarist, the Dutch-born Reg Schwager.

The story of how Peterson first got to know Kelly Green in a seafood restaurant in Sarasota in Florida, and how she became his fourth wife in 1987, is enshrined in the tune “Love Ballade”, which Peterson wrote for her. This part of the film dwells on his memories of loneliness of the road in earlier days.

Then it moves to the story of Peterson’s stroke in May 1993, after which the use of his left hand was severely impaired. He was able to compensate remarkably and keep his playing and career on track.

Perhaps Oscar Peterson: Black + White slides too easily into hagiography. Whereas Avrich’s The Last Mogul dealt with the film executive Lew Wasserman's darker side, he assembled a sizeable cast to heap praise on Peterson. I'm also not sure we need an account of what happened on the morning after Peterson passed away in his sleep, or, indeed, the role played by Smedley the boxer dog.

In the end, though, the film is all about the glory of Peterson’s music. It is not only what underpins and carries the story when this film is at its best, it's also what lasts.

rating

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

Add comment