Like the British high street, the once richly diverse landscape of dance in the UK is likely to look very different once lockdown is fully lifted. There will be losses, noticeably among the smaller companies whose survival was always precarious. There will be downsizings. There will be painful gaps where a major talent has given up the fight, retired to run a flower shop or become a hill farmer. It will take years for the sector to recover.

All the performing arts have taken a hammering, and heaven knows this isn’t a competition, but dance, and ballet especially, is a case apart. The technique that took decades to acquire needs constant maintenance and finessing. The ability of a large corps de ballet to synchronise the flow of arms, the precise angle of legs, even the rhythm of its breathing, is the result of a career-long continuum of training. For many ballet companies one of the few unexpected bonuses of the stay-at-home period of lockdown was the global online interest in their Zoomed morning class – a daily 90-minute testament to the physical hard grind of every dancer’s life. For newcomers to ballet-watching, this was revelatory.

For Kevin O’Hare, artistic director of the Royal Ballet, the lowest point of the past 12 months came last April when he seriously wondered whether the company would survive. The powers that be had briefly considered laying off all 90 of the dancers with a view to re-employing once normal operations could resume. “I think someone very quickly stepped in to say that was a terrible idea. This is not just a group of people who happen to work together. They’ve grown up together, trained together, learned together.” Yet at the same time O’Hare was acutely aware of the company’s reliance on box office revenue, which was, for the foreseeable, nil. As for private sponsorship, the outlook was no better. “If there are no shows, our financial supporters have nothing to see and the whole funding structure crumbles.”

“I think someone very quickly stepped in to say that was a terrible idea. This is not just a group of people who happen to work together. They’ve grown up together, trained together, learned together.” Yet at the same time O’Hare was acutely aware of the company’s reliance on box office revenue, which was, for the foreseeable, nil. As for private sponsorship, the outlook was no better. “If there are no shows, our financial supporters have nothing to see and the whole funding structure crumbles.”

The Royal Ballet had been in jeopardy before. During the Second World War, with its dancers undernourished and most of the men conscripted, it resorted to performing in garrison towns and London parks. In May 1940, on a propaganda tour to Holland, it only narrowly escaped the Nazi invasion. And yet, sustained by a diet of grit and conviction, it came through, presenting in its first full season at Covent Garden in 1945-46 work that mapped out an astounding new path for British ballet.

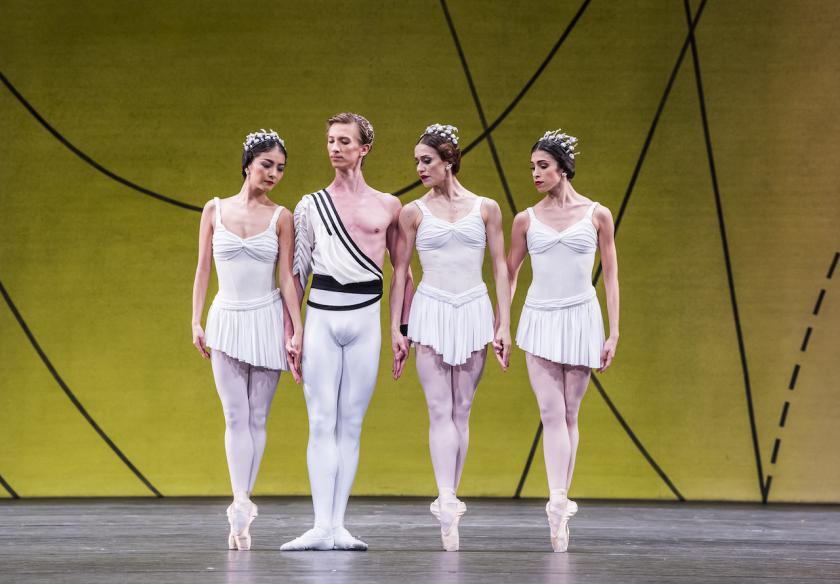

Kevin O’Hare won’t go so far as to compare the company’s recent travails with the trauma of wartime. But it is no coincidence that among the three triple bills announced earlier this week for the Royal Ballet’s return to the stage in June and July is Act III from The Sleeping Beauty, the big work chosen to open the immediate post-War season. A 2016 Insight Evening, talking about and demonstrating elements of that landmark production, is to be streamed, for free, tonight. Equally significant is the company’s most recent digital stream – a snip at £3 – of Symphonic Variations (pictured above and top), one of a handful of new ballets created for that same great 1946 season. The piece was the very first made by Frederick Ashton for the Covent Garden stage, a vaster space than he had ever set foot on, let alone had to fill with shapes and steps. It is extraordinary on a number of counts, not least for its nerve. At a time of national restoration which might have called for grandeur and pagentry, Symphonic, as it quickly became known, was cool and sparse, ancient Greek in its platonic feeling. It filled its 20 minutes with pure classical movement, no nod to either story or character. It was also phenomenally difficult to dance, in part owing to the speed and intricacy of the steps, which for the women at times entails their lower limbs behaving like a swing-needle sewing machine, in part because the six dancers are permanently on stage. It’s a marathon even for today’s elite athletes. In 1946, weakened by wartime rationing, the cast in early run-throughs were pushed to the point of collapse.

Equally significant is the company’s most recent digital stream – a snip at £3 – of Symphonic Variations (pictured above and top), one of a handful of new ballets created for that same great 1946 season. The piece was the very first made by Frederick Ashton for the Covent Garden stage, a vaster space than he had ever set foot on, let alone had to fill with shapes and steps. It is extraordinary on a number of counts, not least for its nerve. At a time of national restoration which might have called for grandeur and pagentry, Symphonic, as it quickly became known, was cool and sparse, ancient Greek in its platonic feeling. It filled its 20 minutes with pure classical movement, no nod to either story or character. It was also phenomenally difficult to dance, in part owing to the speed and intricacy of the steps, which for the women at times entails their lower limbs behaving like a swing-needle sewing machine, in part because the six dancers are permanently on stage. It’s a marathon even for today’s elite athletes. In 1946, weakened by wartime rationing, the cast in early run-throughs were pushed to the point of collapse.

Despite the historic claim that the first cast has never been bettered, it’s possible that the six dancers who feature in the current stream – a stage performance recorded in 2017 – are more than a match for their distant predecessors. Ashton’s ballets are, largely, better coached now than they have been for decades, and some of the contemporary work that the Royal Ballet has tackled may, paradoxically, have left its dancers more alert to the detailed physicality of Ashton style. Witness the radiant serenity this sextet bring to the densely patterned movement, however hard their feet and legs are working. Another challenge for the three men and three women is the requirement for each trio to move as a single entity. The superb camerawork directed by Ross MacGibbon on this recording both flatters the dancers and guides the eye to the choreography’s exquisite symmetries, while also threatening to expose the minutest detail – the tilt of a head, the curl of a finger – that might be out of line. Remarkably, there is none.

The streaming phenomenon is not going away any time soon, but dance is ill-served by small screens

Symphonic also trod new ground in 1946 in its meshing of movement with music, visually transcribing César Franck’s antiphonal writing with insight and wit. Sometimes the steps track the music almost doggedly, the girls taking the piano’s part (fine playing from Paul Stobart), the boys the orchestra. At other times the choreography digresses from the score with startling freedom, substituting the music’s rhythms for its own. A spell is cast when, over hushed piano, Marianela Nuñez, supported by Vadim Muntagirov, appears to skim the width of the stage, resisting the earth’s gravity, her toes barely making contact.

On a mundane note, I feel compelled to record that my experience of this performance was markedly enhanced by the purchase of a new TV set – nothing fancy, not even HD, just a thing that works and sounds as it should. Broadcast dance is ill-served by tiny screens and tinny equipment, and I feel ashamed to have tolerated my old gear for so long. Because, of course, the streaming phenomenon is not going away any time soon. One of the major lessons our ballet companies have learnt in the past year is how to make their work available to an armchair audience, and at a price almost anyone can afford.

Kevin O’Hare is convinced that streaming can co-exist happily alongside live performance, at no detriment to the box office. “I was always a big advocate for the cinema programme and putting ourselves out there. And we plan to continue to put out home streaming in tandem with that. It’s the material we can pack around the filmed performance that interests me – the interviews and rehearsal footage, giving people ways into the art form, to understand what it’s all about. “The other joy of streaming is that things can be viewed more than once. Our communications team have a way of knowing how many times each stream is viewed, and it’s regularly three, four, five times with the shorter ballets. A classic such as Symphonic has the capacity to yield more at each view, so that’s excellent news.” Yes, reader, I was part of that statistic, clocking in three times in as many days.

After so much time away from live performance, the Royal Ballet might be forgiven for approaching the return with caution. But no, there are those three triple bills in June and July, which will include several one-act pieces new to the company, alongside an evening of Draft Works made by dancers themselves. Then in October comes a major new full-evening creation – a work by Wayne McGregor to mark the 700th anniversary of Dante, with a cast of 40 and a new score by Thomas Adès. The first read-through for the orchestra, with the choreographer present, will happen just a month from now. And the first 20 minutes of next season’s other big number – an adaptation by Christopher Wheeldon of the magical-realist novel Like Water For Chocolate – is already in the bag, thanks to lockdown.

“There have been some silver linings in the past year,” O’Hare concedes. “Normally the likelihood of being able to get all the key soloists together with Chris Wheeldon in a studio along with the original writer, Laura Esquivel, who is keen to be involved, would be practically zero. People are busy and their schedules so complicated. In February, they found they were all free.”

For the moment, the not-normal must continue a little longer. The company will carry on doing class in masks, and to allow distance the 90 dancers must continue to be divided between five rooms, which means each dancer getting a live teacher only once every five days. It’s not ideal. Yet as soon as restrictions allow, a series of classes will be held on the Opera House main stage, open to the public.

“The younger dancers in particular always love that,” says O’Hare. “And audiences too. There is something transfixing about seeing dancers at work. You get an inkling of how they transform themselves, how it all happens.”

- Symphonic Variations is available to view on-demand until 2 May (£)

- Tonight, at 7pm, join Director Kevin O’Hare in discussion about the Royal Ballet’s restaging of the production of The Sleeping Beauty that reopened the Royal Opera house in 1946 and this year marks its 75th anniversary (free)

- More dance reviews on theartsdesk

Add comment