Best of 2020: Books | reviews, news & interviews

Best of 2020: Books

Best of 2020: Books

The page-turners, feverish reads and haunting tales of a turbulent year

Stuck in our homes for most of this year, we found comfort and escape from books in ways unprecedented in 2020. The chance to dwell in alternative spaces, or inhabit different rhythms of living.

Some of the outstanding novels published this year got the welcome they deserved; others, as usual, did not. Among the latter was Linn Ullmann’s searching and moving Unquiet (Hamish Hamilton; translated by Thilo Reinhard). This counts as a sort of “autofiction”, but one so much sharper, richer – and wittier – than that dismal tag suggests. In fictionalised form, but with no speculative embroidery, the Norwegian writer revisits her childhood with, and without, her elusive celebrity parents (her mother, the Norwegian actor Liv Ullmann; her father, the Swedish director Ingmar Bergman). Ullmann’s literary artistry, fierce intelligence and rueful, sardonic humour deepen a story of memory, mourning and inheritance in which this child of two limelit solitudes confesses that “I’m trying to understand something about love here”. Gloriously, she succeeds. Boyd Tonkin

Some of the outstanding novels published this year got the welcome they deserved; others, as usual, did not. Among the latter was Linn Ullmann’s searching and moving Unquiet (Hamish Hamilton; translated by Thilo Reinhard). This counts as a sort of “autofiction”, but one so much sharper, richer – and wittier – than that dismal tag suggests. In fictionalised form, but with no speculative embroidery, the Norwegian writer revisits her childhood with, and without, her elusive celebrity parents (her mother, the Norwegian actor Liv Ullmann; her father, the Swedish director Ingmar Bergman). Ullmann’s literary artistry, fierce intelligence and rueful, sardonic humour deepen a story of memory, mourning and inheritance in which this child of two limelit solitudes confesses that “I’m trying to understand something about love here”. Gloriously, she succeeds. Boyd Tonkin

@BoydTonkin

A tempest of chaos, myth and misery, Fernanda Melchor’s Hurricane Season (Fitzcarraldo Editions) served in some ways as a literary precursor for the year that was to come. The novel details the series of events leading up to the killing of a so-called "witch", whose discarded corpse is discovered lying in a ditch in the state of Veracruz, delivering a blend of whodunnit and horror that weaves through issues of misogyny, masculinity, homo and trans-sexuality, poverty and violence. Composed in prose as wild and devastating as its title implies, and formidably translated by Sophie Hughes, the novel earns the label of "page-turner" twice over: both impossible to put down, and shot-through with such sickening and expletive-laden scenes as to render its readers half-desperate to finish. This twisted tale of contemporary Mexico more than earned its shortlisting for the 2020 International Booker. Daniel Baksi

A tempest of chaos, myth and misery, Fernanda Melchor’s Hurricane Season (Fitzcarraldo Editions) served in some ways as a literary precursor for the year that was to come. The novel details the series of events leading up to the killing of a so-called "witch", whose discarded corpse is discovered lying in a ditch in the state of Veracruz, delivering a blend of whodunnit and horror that weaves through issues of misogyny, masculinity, homo and trans-sexuality, poverty and violence. Composed in prose as wild and devastating as its title implies, and formidably translated by Sophie Hughes, the novel earns the label of "page-turner" twice over: both impossible to put down, and shot-through with such sickening and expletive-laden scenes as to render its readers half-desperate to finish. This twisted tale of contemporary Mexico more than earned its shortlisting for the 2020 International Booker. Daniel Baksi

2020 has been a year of nostalgia for halcyon days past or anticipation for regained freedoms of the future. William Boyd, it seemed, promised us a healthy dose of the former in his novel Trio. Taking us back to a film set in sunny sixties Brighton was just the antidote for the claustrophobia of our times. Or so we thought. Pressures of secrecy impose upon Boyd’s three protagonists a weight of anxiety in a novel where telling the truth is never the right thing to do. Once the secrets are out, all hell breaks loose – even if the film itself shows an admirable capacity for change. Trio moves from the promises of sweet solace to page-turning thriller in the blink of a car headlight, leaving the film producer Talbot to ruminate in the closing pages: "We cannot control most aspects of our lives". What a pity that is. Charlie Stone

2020 has been a year of nostalgia for halcyon days past or anticipation for regained freedoms of the future. William Boyd, it seemed, promised us a healthy dose of the former in his novel Trio. Taking us back to a film set in sunny sixties Brighton was just the antidote for the claustrophobia of our times. Or so we thought. Pressures of secrecy impose upon Boyd’s three protagonists a weight of anxiety in a novel where telling the truth is never the right thing to do. Once the secrets are out, all hell breaks loose – even if the film itself shows an admirable capacity for change. Trio moves from the promises of sweet solace to page-turning thriller in the blink of a car headlight, leaving the film producer Talbot to ruminate in the closing pages: "We cannot control most aspects of our lives". What a pity that is. Charlie Stone

The Mirror & the Light by Hilary Mantel (4th Estate). How could anyone who believes in Mantel’s supreme style and characterisations find the last in her Thomas Cromwell trilogy a relative disappointment, or simply too long? There are the same gorgeous stretches of writing – to call it purple prose would be a disservice – and the ever-increasing insights gleaned from the extra years spent with a historical figure not necessarily fascinating in himself but made so by a singular imagination. Afterwards, I went on to read Diarmaid MacCullogh’s biography and it took forever; the novel needed the time that lockdown allowed, but only for savouring, not for struggling through the mundane bits of Cromwell’s political life as happened with MacCullogh. The beauty of it is that now, after two novels where the trajectory at least was known, we can’t begin to guess where Mantel will take us next.

The Mirror & the Light by Hilary Mantel (4th Estate). How could anyone who believes in Mantel’s supreme style and characterisations find the last in her Thomas Cromwell trilogy a relative disappointment, or simply too long? There are the same gorgeous stretches of writing – to call it purple prose would be a disservice – and the ever-increasing insights gleaned from the extra years spent with a historical figure not necessarily fascinating in himself but made so by a singular imagination. Afterwards, I went on to read Diarmaid MacCullogh’s biography and it took forever; the novel needed the time that lockdown allowed, but only for savouring, not for struggling through the mundane bits of Cromwell’s political life as happened with MacCullogh. The beauty of it is that now, after two novels where the trajectory at least was known, we can’t begin to guess where Mantel will take us next.

On the same level of engagement, but a relatively feverish read, The Lying Life of Adults by Elena Ferrante (Europa editions) universalizes the anguish of adolescence in a Neapolitan teenager’s chronicle. And my obsession of the last few months, the people-in-landscapes novels of Willa Cather, is thanks to the special pleading of Alex Ross in his Wagnerism (4th Estate). David Nice

It’s been a good year for books, especially needed as we’ve all been inside for so much of it. James Rebanks’ English Pastoral has been a personal highlight, a book that compellingly and passionately argued that English agriculture must change. Describing his farm’s evolution through three generations, Rebanks demonstrated the heart-breaking degradation of the land in his own lifetime, using this progression to show how things could be different. English Pastoral was so good, in fact, that my farming grandfather insisted that he read it to my grandmother (and I cried). India Lewis

It’s been a good year for books, especially needed as we’ve all been inside for so much of it. James Rebanks’ English Pastoral has been a personal highlight, a book that compellingly and passionately argued that English agriculture must change. Describing his farm’s evolution through three generations, Rebanks demonstrated the heart-breaking degradation of the land in his own lifetime, using this progression to show how things could be different. English Pastoral was so good, in fact, that my farming grandfather insisted that he read it to my grandmother (and I cried). India Lewis

@IndiaLHL

Mecklenburgh Square and its gardens were established in the early 1800s: expensive-looking terrace houses, surrounded by views of fields on either side, built with the intention of attracting wealthy proprietors and their families. Francesca Wade’s Square Haunting: Five Women, Freedom and London Between the Wars (Bloomsbury) chronicles the lives of five women who lived there, whose presence reveals an alternative narrative. In her vivid history, Wade follows modernist writer Hilda Doolittle (H.D.); crime and mystery novelist Dorothy L. Sayers; Eileen Power, famous for her academic writing on medieval women; classicist Jane Harrison; and Virginia Woolf, whose prominent words give Wade’s book its title. Tracking the inhabitants who lived in this square at different times and for varying intervals, Wade’s biography in five parts is cleverly told, with location held firmly at its centre. Not much of the original Mecklenburgh Square remains today; still, Wade’s idiosyncratic prose manages to conjure up an old environment both conducive and in direct opposition to the production of women’s work. Wade’s quintet is compellingly evocative of the spaces, incidents, and persistence for knowledge that dominated these five lives. Olivia Fletcher

Mecklenburgh Square and its gardens were established in the early 1800s: expensive-looking terrace houses, surrounded by views of fields on either side, built with the intention of attracting wealthy proprietors and their families. Francesca Wade’s Square Haunting: Five Women, Freedom and London Between the Wars (Bloomsbury) chronicles the lives of five women who lived there, whose presence reveals an alternative narrative. In her vivid history, Wade follows modernist writer Hilda Doolittle (H.D.); crime and mystery novelist Dorothy L. Sayers; Eileen Power, famous for her academic writing on medieval women; classicist Jane Harrison; and Virginia Woolf, whose prominent words give Wade’s book its title. Tracking the inhabitants who lived in this square at different times and for varying intervals, Wade’s biography in five parts is cleverly told, with location held firmly at its centre. Not much of the original Mecklenburgh Square remains today; still, Wade’s idiosyncratic prose manages to conjure up an old environment both conducive and in direct opposition to the production of women’s work. Wade’s quintet is compellingly evocative of the spaces, incidents, and persistence for knowledge that dominated these five lives. Olivia Fletcher

What would Dickens do? Michael Nath gives us one answer in this, his third novel The Treatment, a twisty tale of the state of modern British race relations. Following one disgruntled journalist’s attempt to piece together the events leading up to and after the unprosecuted 20-year old murder of a black teenager by a white gang, Nath avoids a procedural to look instead at how the racist rot sets in and how it goes untreated. But best of all, as if countering the silence that breeds ignorance about institutional violence, Nath fills his novel with talk. Like Dickens, he’s expert at ‘doing voices’ and ones we don’t tend to hear in a lot of literary fiction – northern, Cockney, working class, immigrant – especially literary fiction which manages to juggle political philosophy and digressions on British common law. Published back in March, The Treatment and its subject only seems to have grown more weighty over the year (already heavy at around 600 pages) but it rides high on its reverence for the gift of the gab. Daniel J Lewis

What would Dickens do? Michael Nath gives us one answer in this, his third novel The Treatment, a twisty tale of the state of modern British race relations. Following one disgruntled journalist’s attempt to piece together the events leading up to and after the unprosecuted 20-year old murder of a black teenager by a white gang, Nath avoids a procedural to look instead at how the racist rot sets in and how it goes untreated. But best of all, as if countering the silence that breeds ignorance about institutional violence, Nath fills his novel with talk. Like Dickens, he’s expert at ‘doing voices’ and ones we don’t tend to hear in a lot of literary fiction – northern, Cockney, working class, immigrant – especially literary fiction which manages to juggle political philosophy and digressions on British common law. Published back in March, The Treatment and its subject only seems to have grown more weighty over the year (already heavy at around 600 pages) but it rides high on its reverence for the gift of the gab. Daniel J Lewis

@_danieljlewis

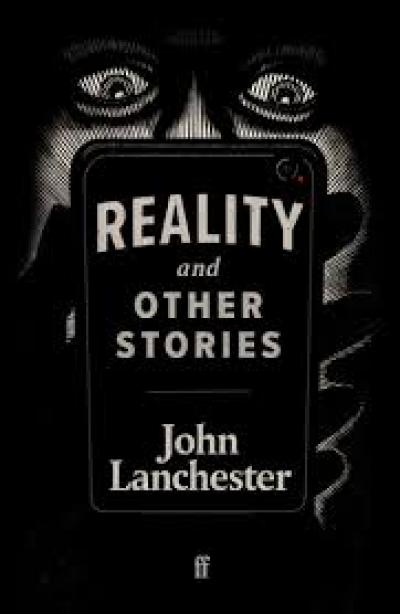

The book I keep recommending this year is John Lanchester’s short story collection Reality, and Other Stories. The stories detail relatable, comfortingly normal middle-class existences – a stressed barrister, young parents visiting a friend’s mansion for the weekend, a pensioner with a job in a charity shop to get him out of the house. But a touch of unease at the near-mythical power of technology, something so ubiquitous to us in 2020, provides the pith. In this piecemeal year, I haven’t wanted to read literature that mirrors that experience – I’d sooner bury myself in fully formed narratives. These stories might have unexplained elements, but structure-wise they are reassuringly whole – strong pieces, simply written, that are gripping rather than fleeting. Lydia Bunt

The book I keep recommending this year is John Lanchester’s short story collection Reality, and Other Stories. The stories detail relatable, comfortingly normal middle-class existences – a stressed barrister, young parents visiting a friend’s mansion for the weekend, a pensioner with a job in a charity shop to get him out of the house. But a touch of unease at the near-mythical power of technology, something so ubiquitous to us in 2020, provides the pith. In this piecemeal year, I haven’t wanted to read literature that mirrors that experience – I’d sooner bury myself in fully formed narratives. These stories might have unexplained elements, but structure-wise they are reassuringly whole – strong pieces, simply written, that are gripping rather than fleeting. Lydia Bunt

@bunt_lydia

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Books

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Robin Holloway: Music's Odyssey review - lessons in composition

Broad and idiosyncratic survey of classical music is insightful but slightly indigestible

Robin Holloway: Music's Odyssey review - lessons in composition

Broad and idiosyncratic survey of classical music is insightful but slightly indigestible

Thomas Pynchon - Shadow Ticket review - pulp diction

Thomas Pynchon's latest (and possibly last) book is fun - for a while

Thomas Pynchon - Shadow Ticket review - pulp diction

Thomas Pynchon's latest (and possibly last) book is fun - for a while

Justin Lewis: Into the Groove review - fun and fact-filled trip through Eighties pop

Month by month journey through a decade gives insights into ordinary people’s lives

Justin Lewis: Into the Groove review - fun and fact-filled trip through Eighties pop

Month by month journey through a decade gives insights into ordinary people’s lives

Joanna Pocock: Greyhound review - on the road again

A writer retraces her steps to furrow a deeper path through modern America

Joanna Pocock: Greyhound review - on the road again

A writer retraces her steps to furrow a deeper path through modern America

Mark Hussey: Mrs Dalloway - Biography of a Novel review - echoes across crises

On the centenary of the work's publication an insightful book shows its prescience

Mark Hussey: Mrs Dalloway - Biography of a Novel review - echoes across crises

On the centenary of the work's publication an insightful book shows its prescience

Frances Wilson: Electric Spark - The Enigma of Muriel Spark review - the matter of fact

Frances Wilson employs her full artistic power to keep pace with Spark’s fantastic and fugitive life

Frances Wilson: Electric Spark - The Enigma of Muriel Spark review - the matter of fact

Frances Wilson employs her full artistic power to keep pace with Spark’s fantastic and fugitive life

Elizabeth Alker: Everything We Do is Music review - Prokofiev goes pop

A compelling journey into a surprising musical kinship

Elizabeth Alker: Everything We Do is Music review - Prokofiev goes pop

A compelling journey into a surprising musical kinship

Natalia Ginzburg: The City and the House review - a dying art

Dick Davis renders this analogue love-letter in polyphonic English

Natalia Ginzburg: The City and the House review - a dying art

Dick Davis renders this analogue love-letter in polyphonic English

Tom Raworth: Cancer review - truthfulness

A 'lost' book reconfirms Raworth’s legacy as one of the great lyric poets

Tom Raworth: Cancer review - truthfulness

A 'lost' book reconfirms Raworth’s legacy as one of the great lyric poets

Ian Leslie: John and Paul - A Love Story in Songs review - help!

Ian Leslie loses himself in amateur psychology, and fatally misreads The Beatles

Ian Leslie: John and Paul - A Love Story in Songs review - help!

Ian Leslie loses himself in amateur psychology, and fatally misreads The Beatles

Samuel Arbesman: The Magic of Code review - the spark ages

A wide-eyed take on our digital world can’t quite dispel the dangers

Samuel Arbesman: The Magic of Code review - the spark ages

A wide-eyed take on our digital world can’t quite dispel the dangers

Comments

Thanks again, Daniel. You've