Anyone whose affection for Rachmaninov is bounded by the Second Piano Concerto or the Paganini Rhapsody might be surprised to learn that his own favourite work of his was his setting for unaccompanied choir of the Vespers, or All-Night Vigil, of the Russian Orthodox Church. Admittedly he uses the Latin “Dies irae” in the Rhapsody, and the “Blagosloven yesi” from the Vigil does battle with it in his Symphonic Dances. But these are no more than Lisztian self-dramatising pieties. The Vigil setting, made at the height of World War I in 1915, is proper, self-effacing piety, and I suspect Rachmaninov loved it precisely because it escaped the indulgent emoting of his concert works and entered the realm of the spiritual.

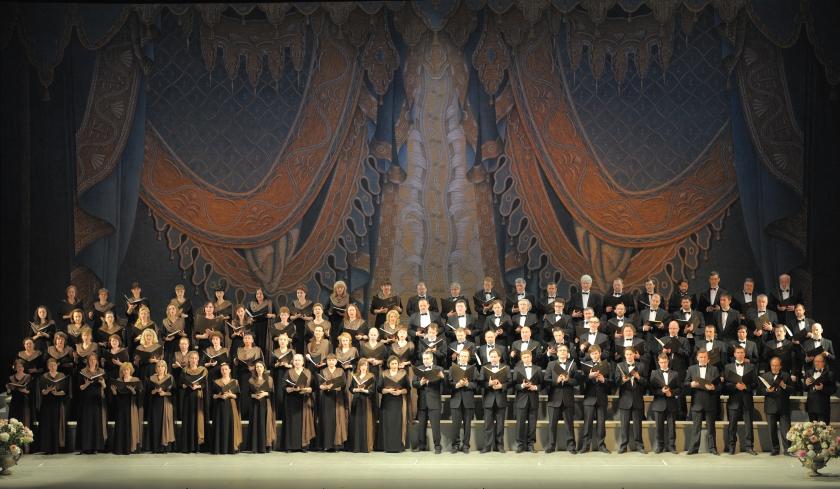

It’s true that in an authentic Russian performance, like the one by the Maryinsky Opera Chorus in Llandaff Cathedral last night, spirit and drama intermingle. Here is no Anglican primness or Catholic groaning. The nearest local comparison might be with a Welsh Valleys choir, devoid of preciosity or timidity, and with a range of expression that covers the whole gamut from prayerful inwardness to explosive joy or protest. But there is still something unique about a Russian choir singing the Orthodox liturgy, something at once raw and refined, a direct line to God cut so many times in the past that it bleeds. It was marvellous to hear this music so grandly done, under Andrey Petrenko, in the echoing spaces of Llandaff, the most beautiful building in South Wales east of St David’s.

An exuberant hubbub, a Madonna framed by angels with trumpetsIt was also suggestive. Rachmaninov wasn’t out on a limb when he wrote the Vigil. He was encapsulating ideas that from the start had formed his own style. You may think the second piano concerto or the second symphony pretty good slush. But wait a minute. Their melodic idiom is almost entirely derived from liturgical chant. In the Vigil, melodies of exactly this sort pick their way through more or less complex textures, often in the middle of an eight- or ten-part polyphony.

Yet polyphony isn’t quite the right word. The right word – a bit technical maybe – is heterophony. This is a method where everyone sings the same tune at the same time but with different tweaks or ornaments, which is something the Welsh do too, in an ancient style called Penillion. What is perhaps peculiarly Russian is the sense of a chanter tune with multiple descants, a kind of rich embroidery above and below the tune itself. This is very different from the highly organised vocal counterpoint of a composer like Byrd or Tallis. It’s less discourse, more a kind of exuberant hubbub, a Madonna framed by angels with trumpets. It takes a special talent to sing it well.

The point is that Rachmaninov (pictured right) based himself on traditional chant, whether Muscovite, Kievan or Greek. But unlike Tchaikovsky before him, he didn’t feel obliged (legally so in Tchaikovsky’s case) to respect the limitations of the old conventions. His settings are sometimes harmonically plain; but often they are not. They become a hyper-modern extension of the conventions, more elaborate, in fact, than anything in the concert works.

The point is that Rachmaninov (pictured right) based himself on traditional chant, whether Muscovite, Kievan or Greek. But unlike Tchaikovsky before him, he didn’t feel obliged (legally so in Tchaikovsky’s case) to respect the limitations of the old conventions. His settings are sometimes harmonically plain; but often they are not. They become a hyper-modern extension of the conventions, more elaborate, in fact, than anything in the concert works.

The Maryinsky singers, fifty or so voices unsupported by instruments (which are not allowed in Russian Orthodox churches), were sure-footed throughout, somewhat strident in fortissimo, then suddenly quiet and intense, always controlled, intonation mostly secure despite the pressure on the voices. And what a range of colour: the basses sinking to a cavernous B flat, bright, resonant sopranos, dark-toned middle voices, including a haunting contralto soloist, Maria Shuklina.

My own favourite pieces are the Kievan “Svete tikhy” (“The Gentle Light”), with its strange parallel chordings, and the beautiful Magnificat, a piece that would enrich an Anglican cathedral evensong. But the whole work is a gallery of such icons. It ideally needs to be heard in Moscow’s Uspensky Cathedral or the Nikolsky in St Petersburg. But Llandaff, packed to the doors, was a more than worthy substitute.

Add comment