Chopin: Études op.10 & op.25 Yunchan Lim (Decca)

Chopin: Études op.10 & op.25 Yunchan Lim (Decca)

Chopin Nicolas van Poucke (Night Dreamer)

I’m reviewing these two Chopin discs by a pair of young men together, even though there are lots of differences between their playing, and the way the albums have been put together. Yunchan Lim is just 20, the youngest ever winner of the Van Cliburn competition, in 2022. His first album, on Decca, is of Chopin’s Études (the op.10 and op.25 sets), which are favourites of mine, and perfect “young man’s music” in their unashamed show-offiness and heart-on-sleeve emotionalism. That they are technically demanding is a given, but Chopin goes well beyond writing mere practice exercises, and Lim’s playing captures the spirit of the music in what is a well-judged debut album.

There are of course fireworks, and the fast and loud playing is executed with stunning strength and velocity. There is perhaps more of a test of mettle in the slower numbers like the beautiful op.10 no.3, which is played with a lovely cantabile line at a no-nonsense tempo – although Lim can’t resist making the middle section more of a flashy workout that it needs to be. That is more fitting to the stormy no.4, with its flying left-hand passagework and heroic demeanour that Lim is happy to assume, but he is able to switch to a more genial mode in the black-note no.5. No.6 is one of the most extraordinary piece Chopin wrote, in its “advanced” chromaticism and anguished melodic shapes. Lim is unindulgent in his tempo and his humble playing means this piece hits home.

I can’t discuss each one, but will say that Lim maintains his standards through the disc, into the op.25 set (I loved the gorgeous, rippling no.1 and the almost ragtime insouciance of no.9). He characterises each piece clearly, even if he is most at home in the dashing, full-on ones like the “Revolutionary” study (his left-hand technique is quite extraordinary). It may feel like there are already enough good pianists out there to last a lifetime, but when someone this good comes along you have to acknowledge it, and acclaim a major talent.

Nicolas van Poucke’s Chopin compendium is the first “direct-to-disc” album I have heard. The process involves, as the name suggests, the performance going straight onto a master tape, without takes being edited together, or any sympathetic effects added. It makes for the “honest” experience of the concert hall, but perhaps without the polish of a regularly edited disc. Where Lim focuses on just the Études, van Poucke’s album is a grab bag: a prelude, a polonaise, a nocturne, four mazurkas, three waltzes and a ballade. A bit of everything, but nicely ordered – and in long takes. It isn’t just that each piece goes direct to tape, but that, for example, the nocturne and four mazurkas run straight through in a single 17-minute track. It’s a feat of concentration and focus, if nothing else.

Nicolas van Poucke’s Chopin compendium is the first “direct-to-disc” album I have heard. The process involves, as the name suggests, the performance going straight onto a master tape, without takes being edited together, or any sympathetic effects added. It makes for the “honest” experience of the concert hall, but perhaps without the polish of a regularly edited disc. Where Lim focuses on just the Études, van Poucke’s album is a grab bag: a prelude, a polonaise, a nocturne, four mazurkas, three waltzes and a ballade. A bit of everything, but nicely ordered – and in long takes. It isn’t just that each piece goes direct to tape, but that, for example, the nocturne and four mazurkas run straight through in a single 17-minute track. It’s a feat of concentration and focus, if nothing else.

But it is more than that, too. The sequencing is very thoughtful, offering nice switches and hints of a four-movement symphonic structure. Van Poucke, a Dutch pianist who has played recitals at the Amsterdam Concertgebouw and the Festival Hall in London, is less concerned with display than Lim. Not that his playing lacks assurance, but it is perhaps more inward, more ruminative. Or maybe that is just the differences in repertoire choices. The playing is sensitive and nuanced, especially in the F-sharp Polonaise op.44, with some lovely voicings in the inner parts, and whose weightiness belies Chopin’s reputation as a miniaturist. The mazurkas are very elegant, not as rustic as other players make them, and the waltzes (including the “Minute” at a sensible speed) sparkle. There is more meat in the Ballade no.1 op.23, that rounds things off, and which van Poucke plays with a gradually emerging sense of wonder that blossoms into something wonderfully expansive and dramatic. Bernard Hughes

Samuel Andreyev: In Glow of Light Seclusion (Métier)

Samuel Andreyev: In Glow of Light Seclusion (Métier)

Here’s a beautifully presented and performed collection of music by Canadian composer Samuel Andreyev. His 22-minute Sonata da Camera makes for a rather dour album opener, so I’d advise skipping forward to In Glow of Light Seclusion, a cantata for soprano and chamber ensemble using texts by the British poet J. H. Prynne. Andreyev refers to their “intricate, lattice-like structures that weave together different fields of reference”, setting them to equally intricate music. The tiny impromptu separating the third and fourth poem is especially ear-catching, celesta and mandolin adding astringent splashes of colour. Soprano Peyee Chen tackles Andreyev’s soaring, lyrical lines with a confidence suggesting that she fully understands Prynne’s dense prosody, even if we don’t; phrases like “solo integrated life spell” and “wild reject obtuse thrown down whenever on” left me baffled. Just sit back and enjoy the sound of the thing.

Vérifications is described as cartoon music, “a mad caper” scored for cut-down versions of regular instruments. Piccolo, musette and piccolo clarinet squeal away merrily in what Andreyev compares to a four-movement compressed symphony. A Sextet in Two Parts features more quirky scoring (basset horn, percussion and cello featuring in the lineup), the individual voices combined to alluring effect in the second movement's ghostly chorale. Intriguing, distinctive music, performed with enthusiasm and impressive accuracy by the Ensemble Proton Bern under Luigi Gaggero.

Michael Zev Gordon: The Impermanence of Things BBC Symphony Orchestra, London Sinfonietta et al (NMC)

Michael Zev Gordon: The Impermanence of Things BBC Symphony Orchestra, London Sinfonietta et al (NMC)

British composer Michael Zev Gordon (b.1963) is well represented in this portrait disc, which features three pieces, all dating from the last 15 years, all large-scale in conception, but which are broken up into smaller shards of music which are constantly and colourfully in dialogue with each other. The composer writes of his delight in “mixing together diverse materials and styles in the same piece”, making him stylistically impossible to pin down – but he rejects the label “postmodern” as his fragmentation, quotation and transformation isn’t playful, but very serious in its intent, exploring themes such as “memory, loss and transitoriness.”

Bohortha, a seven-movement orchestral suite, the busy outer movements are planets orbiting round the “still centre” of the fourth. It is beautiful in its stasis, but also feels earned. “On Gossamer Wings” has a fleetness of foot in which the BBCSO clearly enjoy running with, while the “Terrifying Angel” is as stern and monumental as “Broken Pieces” is jagged and mercurial. The last movement, “Bohortha”, is named after a tiny Cornish hamlet, and reminded me of Charles Ives, with its layers of different textures set against each other. It’s all very nicely paced, by both composer and conductor (Jukka-Pekka Saraste). The Violin Concerto, played by Carolin Widmann and the BBC National Orchestra of Wales under Catherine Larsen-Maguire, is more continuous in its surfaces, and longer-breathed in its construction. Zev Gordon liked the “strained and fragile” quality of Widmann’s playing, and this is given full rein: this is not a heroic concerto in the Beethoven mould. Rather it is a more internalised monologue for the violin, with a beautifully painted orchestral accompaniment, and Widmann gives a committed and dramatic reading. The final few minutes are gorgeous.

The Impermanence of Things is something completely different. Back to the miniaturist approach, here Zev Gordon pits the London Sinfonietta (conducted by Ryan Wigglesworth) with Huw Watkins on piano and Ian Dearden’s electronics. With just-out-reach references to other pieces, and a patchwork structure, the piano is like a planet around which the ensemble orbits. Watkins is quicksilver in his switching of personality and tone (movements IX and XI are particularly winning), the Sinfonietta razor sharp in their interjections, with the electronics contributing a kaleidoscopic sheen. The three pieces were all recorded at live concerts, in the Barbican, Hoddinott Hall and LSO St Luke’s respectively, but there is no lack of polish in the performances and neither is there any jarring between the sound of the three venues – credit for this to David Lefeber, who mastered the disc. Bernard Hughes

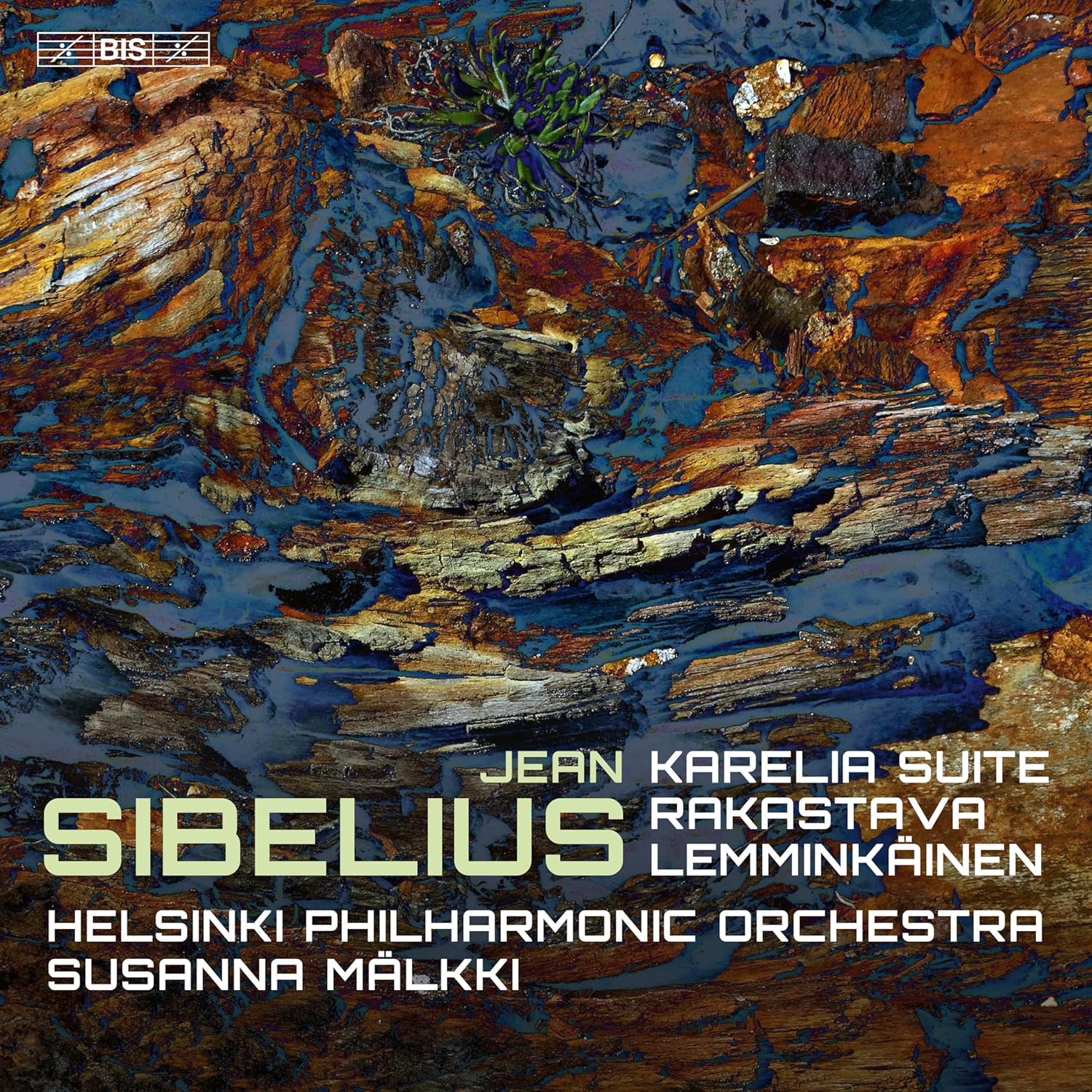

Sibelius: Karelia Suite, Rakastava, Lemminkäinen Helsinki Philharmonic Orchestra/Susanna Mälkki (BIS)

Sibelius: Karelia Suite, Rakastava, Lemminkäinen Helsinki Philharmonic Orchestra/Susanna Mälkki (BIS)

Sibelius’s stylistic range could be astonishing, as demonstrated by the three works on this generously filled BIS disc. Each began life in the mid-1890s, the works variously revised and tweaked in subsequent decades. That they’re from the same pen is never in doubt, though it’s still a shock to jump from the Karelia Suite’s jaunty “Alla marcia” to the dense, doomy brass chords of “Lemminkäinen in Tuonela”. Then there’s the three-movement suite drawn from Rakastava, originally written for tenor and male choir in 1894 and radically recast later for strings, timpani and triangle. It’s exquisitely handled here, Suzanna Mälkki’s Helsinki Philharmonic strings heart-stopping in the tiny central “The Path of His Beloved”, one of the most sheerly Sibelian things that Sibelius composed. It’s gorgeous. As is Mälkki’s Karelia Suite, the “Intermezzo” opening in wonderfully mysterious fashion before the trumpets enter and things perk up. The “Ballade” is perfectly paced, Paula Malmivaara’s soulful cor anglais solo a highlight.

Lemminkäinen is on a different scale, the four movements (or Legends?) adding up to 50 minutes here, making it feel like a symphony that’s slipped through the net. It predates the composer’s official Symphony No. 1, though a mixed critical reception prompted Sibelius to revise and then withdraw the work. The Swan of Tuonela and Lemminkäinen’s Return found life as standalone pieces, Sibelius finally publishing the two longest movements in 1939. A shaggy tale of seduction, dismemberment and rebirth, Lemminkäinen contains some of Sibelius’s most colourful and viscerally exciting music. I enjoyed Sakari Oramo’s recent Chandos recording, but Mälkki’s boasts even better playing and spectacular widescreen sound. The textural and harmonic boldness of “Lemminkäinen in Tuonela” is startling, setting us up for the magically reassembled hero’s triumphant journey home, Mälkki whipping up a real storm. Fabulous, in other words – you can never have too much Sibelius.

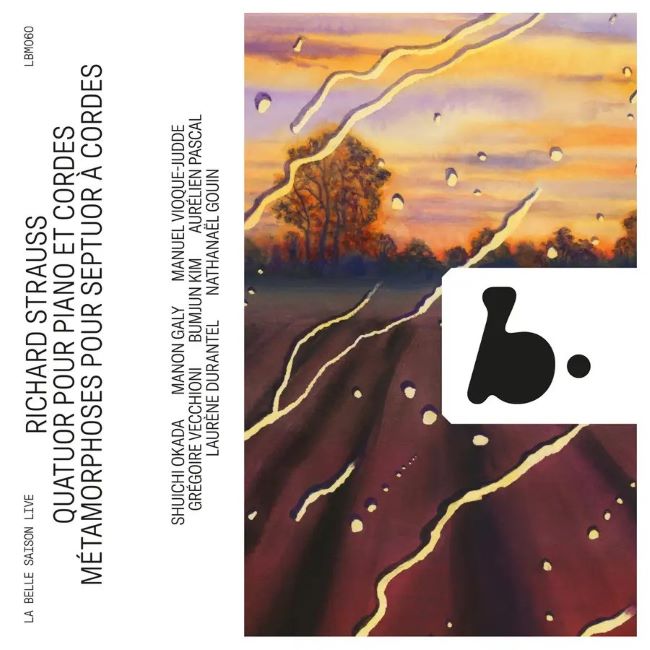

Richard Strauss: Piano Quartet and Metamorphosen (septet version) Trio Arnold, Manon Galy, Grégoire Vecchioni, Aurélien Pascal, Laurène Durantel (strings), Nathanaël Gouin (piano) ( b·records)

Richard Strauss: Piano Quartet and Metamorphosen (septet version) Trio Arnold, Manon Galy, Grégoire Vecchioni, Aurélien Pascal, Laurène Durantel (strings), Nathanaël Gouin (piano) ( b·records)

The b·records label from Bordeaux has as its motto “Du live et rien d’autre” (live and nothing but); this record of two chamber works by Richard Strauss was recorded in a concert at Coulommiers, 60km due east of Paris, in November 2023. The latter half is made up of the original septet version of Metamorphosen, in an edition made by Rudolf Leopold from the original manuscript which was re-discovered in 1990. On the positive side, this is very classy string playing of real beauty, poise, elegance and expressiveness. But I found myself definitely wanting more ache and more urgency. Quick comparisons, either with a 23-strings version like Kempe/ Dresden, or the particularly fine recording of the septet version by Marianne Thorsen and the Nash Ensemble from 2006, brought out the pathos which was missing here.

The first piece on the record is far more recommendable. The Piano Quartet is from six decades earlier in Strauss’s long life, 1884/5, and has wonderful verve and clarity. I found the second movement “Scherzo: presto” with its fireworks irresistibly effervescent; the energy and drive coming from pianist Nathanaël Gouin - his teachers/mentors include the great Maria Joao Pires - are superb. There is beauty and delicacy in the “Andante” third movement. As a live performance, this really does take wing, and the last movement's 10 minutes never flag. Balance and recorded sound are superb. Sebastian Scotney

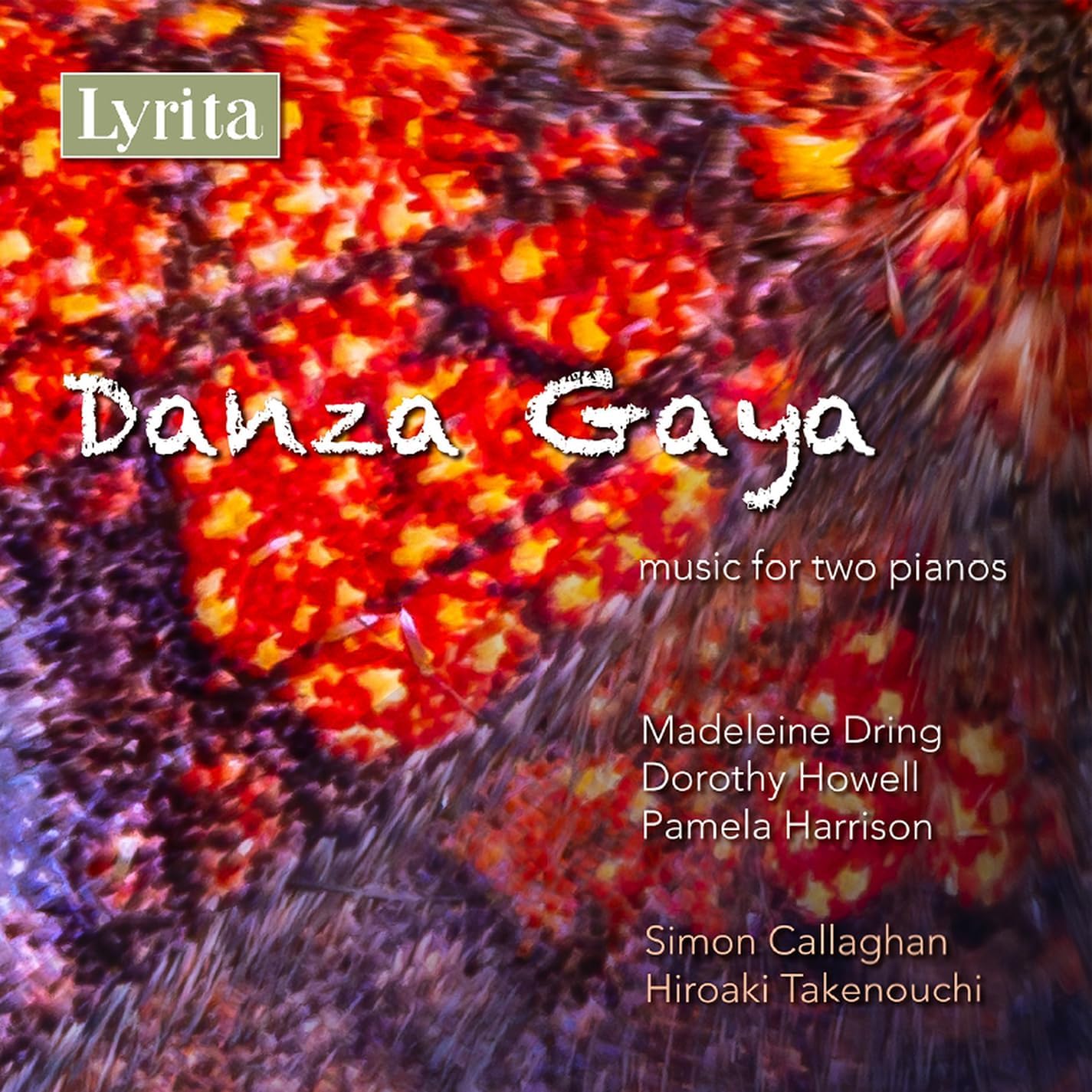

Danza Gaya: music for two pianos by Madeleine Dring, Dorothy Howell and Pamela Harrison Simon Callaghan, Hiroaki Takenouchi (Lyrita)

Danza Gaya: music for two pianos by Madeleine Dring, Dorothy Howell and Pamela Harrison Simon Callaghan, Hiroaki Takenouchi (Lyrita)

Some recordings arrive at exactly the right time, and Danza Gaya turned up after a long, stressful day and some inclement early spring weather. Madeleine Dring’s two-minute title track is better-known as a piece for oboe and piano, the composer noting that it “can be played with a slightly lazy feel or a little faster.” Simon Callaghan and Hiroaki Takenouchi’s effervescent two-piano version wins extra points by doing the latter, and will satisfy a craving you didn’t think you had. The bouncy bossa nova rhythms are synchronised to perfection, and you’ll be compelled to listen to it on a loop – on its own terms, “Danza Gaya” is a pocket-sized masterpiece. Callaghan and Takenouchi follow it with three more frothy dances, though the most substantial work here is an impressive 1951 Sonata for Two Pianos. Concise and serious-minded, it was received with bafflement by critics. We get two enjoyable sets of pieces for learners, Dring relishing the need “to try to write music that was attractive within a limited technical range.”

Also on the disc are works by Dorothy Howell (1898-1982) and Pamela Harrison (1915-90). Howell’s impressionistic, evocative Recuerdos Preciosos was composed in 1934 after a trip to Barcelona, its two movements inspired the stillness of the city’s gothic cathedral and the amusements at Tibidabo. 1920’s short, virtuosic “Spindrift” was Howell’s signature piece, brilliantly played here. Harrison’s Dance Little Lady dates from 1976, an entertaining sequence of six quirky dances. The closing “Tempo Giusto” sounds like pealing bells, the clangourous final chords brilliantly caught by producer Adrian Farmer. Excellent, detailed sleeve notes by Leah Broad seal the deal. Trust me: you NEED this album.

Add comment