Mozart: The Piano Sonatas (Robert Levin, playing Mozart’s fortepiano) (ECM New Series)

Mozart: The Piano Sonatas (Robert Levin, playing Mozart’s fortepiano) (ECM New Series)

There is no doubt about the brilliant uniqueness of pianist, conductor, musicologist and one-time Nadia Boulanger pupil Robert Levin, an influential Harvard Professor for more than two decades until his retirement in 2014. Turn the clock back 30 years, and Levin’s presentational style was much more disputative back then than it is these days: in a memorable contribution to Derek Bailey’s 1992 Channel 4 series on improvisation “On the Edge” he railed against Mozart performances that were “interchangeable, middle of the road, not very interesting or challenging, and above all concerned with the outlines of compositions and not with their inner content.”

Whereas the thrust of the logic he applies has remained consistent, these days, with his 75th birthday just around the corner, and his ideas far more accepted than they were, his combative edge has softened. The battles won, he prefers to dwell on explaining the historical rationale for the way he approaches the music. In the video statements by him which ECM has produced, and the piece he has written in the 100-page booklet (which also contains substantial essays by Ulrich Leisinger of the Mozarteum University in Salzburg) there is a wealth of detail about performance practice. In the performances here, the listener soon gets used to the idea that after a theme has been stated for the first time, decoration, ornamentation, decoration and improvisation will always be the norm. Levin has also worked extensively throughout his adult life on the incomplete fragments which Mozart never turned into completed works, notably a fascinating G minor sonata movement K. 312, which is now believed to have been written in 1790. It is the closing piece on the seventh and last disc of this set.

The instrument on which the whole set is recorded is known to have been Mozart’s main concert instrument: a five-octave, 61-key fortepiano. Although it has no maker’s mark, Leisinger says it “can be attributed with great likelihood” to Johann Gabriel Walter. The likely date of construction, 1782, would make it one of Walter’s earlier instruments. Leisinger is very dismissive of the oft-made claim that the instrument was substantially rebuilt after Mozart’s death. The 7-CD ECM set, from two sessions a year apart in 2017 and 2018, is all recorded on this instrument. And therein lies a problem. Whereas the 1805 Walter instrument on which Kristian Bezuidenhout recorded his extensive Mozart set for Harmonia Mundi from 2009 onwards was built after Mozart’s death, and therefore strictly speaking is an anachronism, it essentially makes a far more agreeable sound. As does the modern copy of a 1795 Walter instrument upon which Ronald Brautigam recorded his set for BIS in 1996-97. The Levin set may have the absolute authority of being played on the instrument owned and extensively played by Mozart himself, but, put simply, it is far easier to listen to the sound made by Brautigam or Bezuidenhout for pleasure than it is to spend time with this new Levin set. - Sebastian Scotney

Emile Jaques-Dalcroze: Works For Violoncello & Piano Pi-Chin Chien (cello), Bernhard Parz (piano) (TYXart)

Emile Jaques-Dalcroze: Works For Violoncello & Piano Pi-Chin Chien (cello), Bernhard Parz (piano) (TYXart)

Émile Jaques-Dalcroze (1865-1950, Swiss, but born in Vienna as Émile-Henri Jaques) has certainly left his mark on music, as a pioneering music educator. It was when a conducting job in a theatre took him to Algiers (and before he studied composition with Bruckner – and clashed badly with him) that a fascination for humans’ natural capacity to absorb rhythm took hold. He started a “School of Rhythmics” at Hellerau in Dresden in 1911 which was closed by the Nazis. There is an Institut Dalcroze in Geneva teaching his methods which has been in continuous existence since 1915, and a sister organisation in the Saint-Gilles area of Brussels. Dalcroze UK has been operating ever since 1926.

Dalcroze also composed: operas, operettas, 19 volumes of pieces for teaching, and either 500 or 1200 songs (depending on source). Plus these very finely crafted and little-known pieces for cello and piano from various stages of the composer's life which are receiving their world premiere recording. Cellists on the look-out for encore pieces will find themselves very well served by at least a couple of them. "Gaîment animé", the fourth of the "Rythmes délaissés" from 1924, is delightfully perky, and ends in a real flourish. The detailed sleeve note points to a possible influence on some later pieces by Martinů who lived in Paris at the time. "Bagatelle", the third of the "3 Morceaux" Op. 48 from 1902, has real melodic heft and encourages the cellist to dig properly into the strings. The whole programme is characterfully and extrovertly played by cellist Pi-Chin Chien and Bösendorfer pianist Bernhard Parz, and has been very well recorded at the studios of Swiss Radio (SRF) in Zurich. The TYXArt label from Nittendorf in Bavaria sets itself very high standards indeed for the accompanying material and the design: the sleeve-note by Swiss writer Walter Labhart is superb, and I loved Yvonne Schmidlin’s cover art. A very happy discovery. - Sebastian Scotney

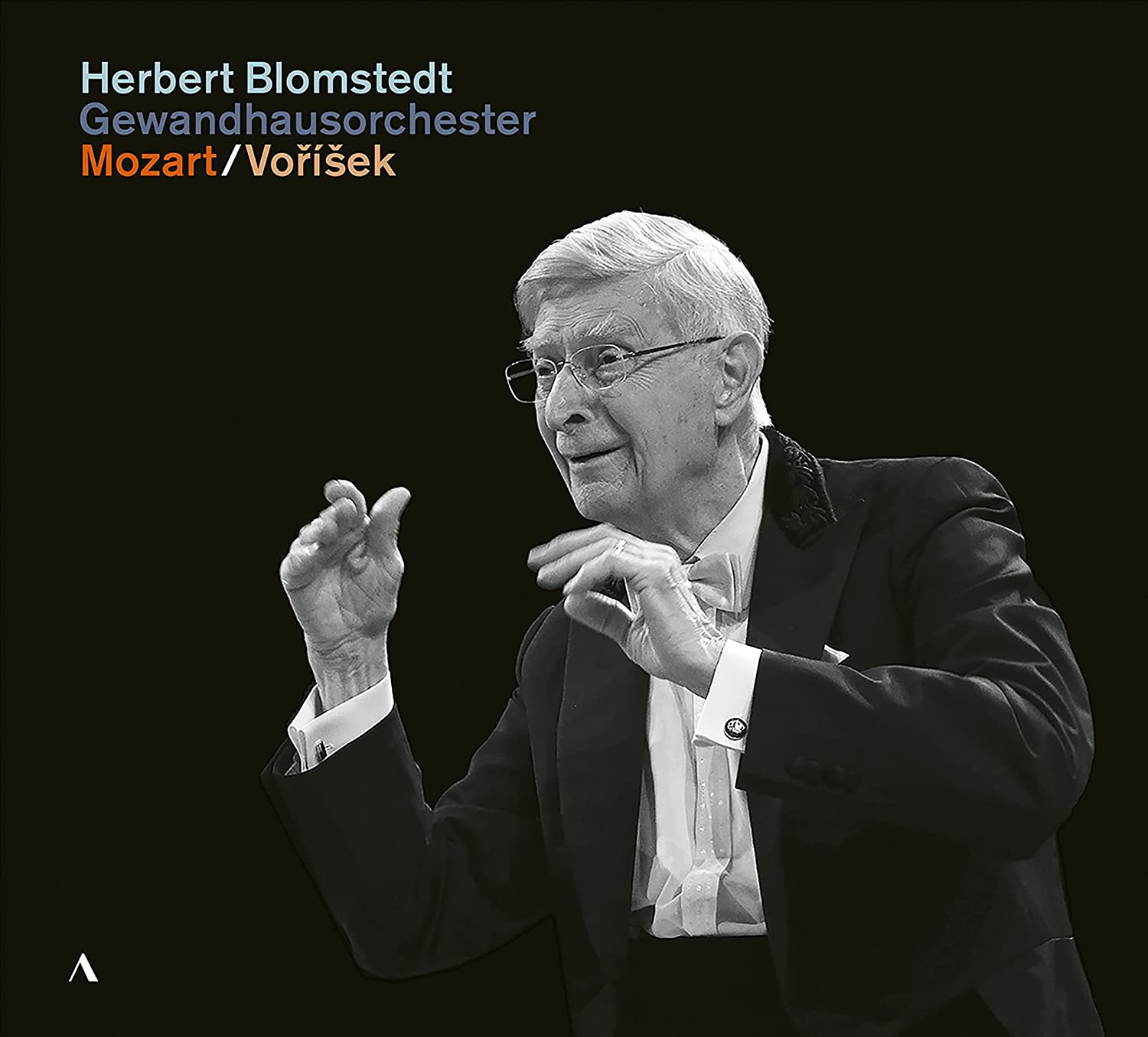

Mozart: Symphony No. 38, Voríšek: Symphony in D major Gewandhausorchester Leipzig/Herbert Blomstedt (Accentus)

Mozart: Symphony No. 38, Voríšek: Symphony in D major Gewandhausorchester Leipzig/Herbert Blomstedt (Accentus)

You’d occasionally spot Jan Václav Voříšek’s name on the covers of Supraphon LPs back in the day, and this short-lived Bohemian composer’s sole Symphony in D has been recorded by the likes of Ancerl and Mackerras. Born in 1791, Voříšek’s teachers included Hummel but, despite his talents impressing Beethoven and a close friendship with Schubert, the difficulties of earning a living as a musician in early 19th century Prague prompted the young composer to study law in Vienna, and he became a civil servant. In 1823, he finally secured a post as an organist, dying in Vienna a year later. The Symphony is a real find, audibly influenced by Schubert and Beethoven but with a very distinct personality. Voříšek’s wind writing reflects his Prague training (listen to the horn writing in the scherzo) and there’s an intriguing harmonic boldness in the first two movements, the B minor “Andante” particularly striking. The finale’s energy threatens to tip into hysteria at several points before an exultant close. This 2020 recording is marvellous, the Gewandhaus directed by a sprightly 93-year old Herbert Blomstedt in a performance dedicated to the orchestra’s former conductor Vaclav Neumann.

Blomstedt’s more familiar coupling is Mozart’s Symphony No. 38. Rhythms in the first movement’s fast section are beautifully sprung, the interplay between strings and winds perfectly caught. Blomstedt’s audible love for the music never prevents things from moving along, and hearing Mozart played with love by a large-scale group on modern instruments is a real treat. A lovely disc, warmly recorded.

Rachmaninov: Piano Concertos 2 & 4 Anna Fedorova, Sinfonieorchester St. Gallen/Modestas Pitrenas (Channel Classics)

Rachmaninov: Piano Concertos 2 & 4 Anna Fedorova, Sinfonieorchester St. Gallen/Modestas Pitrenas (Channel Classics)

Rachmaninov’s Fourth Piano Concerto doesn’t get enough love. Completed in 1926 and later radically revised, it’s appreciably different from Nos. 2 and 3; the scoring leaner, the harmonies more astringent. Do seek out Alexander Ghindin’s recording of the composer’s first version on Ondine (conducted by Vladimir Ashkenazy), showier and more overtly romantic than the tauter 1941 revision. Ukrainian pianist Anna Fedorova sees the concerto as “a farewell to the past and a dive into a quite terrifying future”, and her performance accentuates the edginess and rhythmic punch, Channel Classics’ recording balance revealing a wealth of orchestral detail often buried. We’re not a million miles away from Rachmaninov’s Symphony No. 3 and Symphonic Dances, the concerto making more sense as a work written mostly in New York. Modestas Pitrenas’ hard-working Sinfonieorchester St Gallen relish the isolated splashes of technicolour, and the finale’s clattering coda is as exultant as it is unsettling. Yes, the slow movement melody resembles “Three Blind Mice”, but it’s still fabulous. Fedorova’s playing is louche in all the right places, especially in the bluesy transition to the “Allegro vivace”.

This performance of Concerto No. 2 is less distinctive, but it’s more than decent. I like Fedorova’s understated “Adagio sostenuto” and there’s some lovely clarinet playing near the movement’s opening, Pitrenas also letting us hear the soft pizzicato string backing. Rachmaninov’s finale pretty much plays itself, and the big moments here are refreshingly free of bombast. Very good, then, but you need this disc for Fedorova’s 4th Concerto.

Shostakovich: Symphonies 6&9 BBC National Orchestra of Wales/Steven Lloyd-Gonzalez (First Hand Records)

Shostakovich: Symphonies 6&9 BBC National Orchestra of Wales/Steven Lloyd-Gonzalez (First Hand Records)

Shostakovich’s 6th and 9th Symphonies make a good pairing on disc; both works are concise and accessible. Avoid Bernstein’s ponderous late DG performances with an under-rehearsed Vienna Philharmonic and get this one instead. Conductor Steven Lloyd-Gonzalez was a name new to me, but he understands the Shostakovich idiom well and secures pin-sharp, colourful playing from the BBC National Orchestra of Wales. Symphony No. 6 was expected to be a large-scale choral work setting a poem by Shostakovich’s one-time friend and collaborator Vladimir Mayakovsky; what was actually premiered in 1939 was a three-movement instrumental work, a huge, tragic “Largo” followed by a pair of flippant scherzos. Lloyd-Gonzalez’s dogged, patient approach really works in the opening movement, the big outburst six minutes in a real shocker. Flautist Matthew Featherstone’s extended solos are superb, and listen to the strings singing out just after 16 minutes in. The “Allegro” is hectic but well-controlled, its closing wind-down beautifully handled, and the goofy finale is a riot.

Symphony No. 9 wasn’t what the Soviet authorities were anticipating, either, this pithy five-movement work baffling critics who were hoping for a brassy celebration of wartime victory. Condemned for its “ideological weakness”, Symphony No. 9 is a subversive delight. This performance boasts excellent wind and brass playing and more nifty tempi in the faster movements. The third movement’s blowzy trumpet solo is terrific, and bassoonist Joshua Wilson’s big soliloquy is heart-breaking. An unexpected treat, beautifully recorded; best ignore the cover art, which looks as if it was drawn in biro on a grubby napkin. Can we have more from this team please?

Add comment