You will doubtless have seen the protestors who dress as Gilean handmaids to protest anti-abortion legislation from Texas to Missouri. They model their costumes on those of the television adaptation of The Handmaid’s Tale: tight white bonnets and red smocks. They appear at courthouses and state capitols as a warning from the near-future or a fiction which feels ever more like the present – and the truth. Thirty-five years and much hype later, Atwood has given us a sequel, The Testaments. “Dear Readers,” she wrote recently on social media, “Everything you’ve ever asked me about Gilead and its inner workings is the inspiration for this book. Well, almost everything! The other inspiration is the world we’ve been living in.”

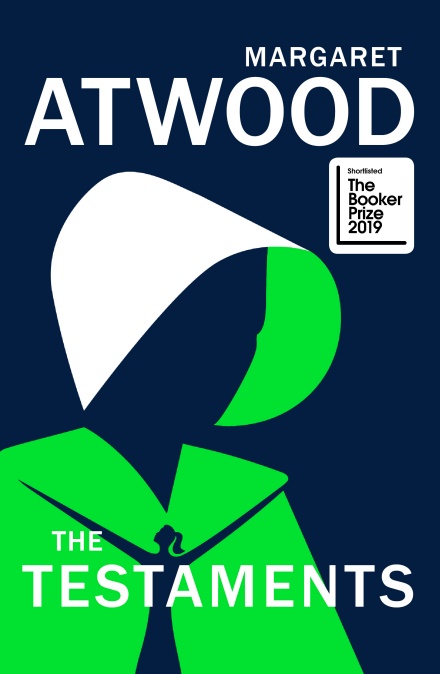

The universe of The Handmaid’s Tale – the 1984 novel, the 1990 film, the 2017 television series – bleeds in and out of the real, and her publishers are cannily aware of it. “You hold in your hands a dangerous weapon loaded with the secrets of three women from Gilead,” announces the dustjacket of The Testaments, “They are risking their lives for you. For all of us.” It adds, ominously, “Before you enter their world, you might want to arm yourself with these thoughts: Knowledge is power and History does not repeat itself, but it rhymes.”

The book dances with the present moment – in the Anglosphere but particularly in North America – in a way that The Handmaid’s Tale did not. In 2012, Atwood wrote about the latter, “The book came out in the UK in February 1986, and in the United States at the same time. In the UK, which had had its Oliver Cromwell moment some centuries ago and was in no mood to repeat it, the reaction was along the lines of, ‘Jolly good yarn’. In the US, however – and despite a dismissive review in the New York Times by Mary McCarthy – it was more likely to be: ‘How long have we got?’”

The Testaments has arrived just as Americans have started to feel that the end may be imminent: access to abortion is being strangled at state level, as indeed are basic women’s health services that tend to be provided in the same facilities. She updates the 1980s past of The Handmaid’s Tale, adding an “excess of choice” and glut of pornography as well as the now predictable cocktail of climate collapse disasters: forest fires, droughts, “refugee riots” in England and Italy. Is Gilead our history? Do its women exist alongside us, or are they long dead? Is Gilead yet ahead of us?

The Testaments is narrated by three women in the form of two witness transcripts and one holograph (a rather quaint projection of the future which feels très 1970s). The novel concludes in the year 2197 with a lecture at “The Thirteenth Symposium” from Professor Pieixoto (who you will recognise from The Handmaid’s Tale). If Offred’s tapes were presented as a single, though rich, historical source, they also provided a narrow window into Gilead – and famously left the fall of the regime unexplained. The Testaments pans out, taking in a more comprehensive view of Mayday operatives working to get Handmaids out of Gilead on the “Underground Femaleroad” and Gilead’s inner administrative workings.

The Testaments is narrated by three women in the form of two witness transcripts and one holograph (a rather quaint projection of the future which feels très 1970s). The novel concludes in the year 2197 with a lecture at “The Thirteenth Symposium” from Professor Pieixoto (who you will recognise from The Handmaid’s Tale). If Offred’s tapes were presented as a single, though rich, historical source, they also provided a narrow window into Gilead – and famously left the fall of the regime unexplained. The Testaments pans out, taking in a more comprehensive view of Mayday operatives working to get Handmaids out of Gilead on the “Underground Femaleroad” and Gilead’s inner administrative workings.

The holograph is authored by Aunt Lydia, the terrorising teacher from the Rachel and Leah Centre for Handmaids-to-be in The Handmaid’s Tale. The witness transcripts are from two much younger women – Agnes Jemima, who is born into the regime and knows nothing other than the party line, and Canadian teenager Daisy, who later goes by Jade. Agnes was snatched from a runaway handmaid but is official daughter to a Commander; she grows up believing in her body’s unwittingly incendiary potential, which might cause men to “stagger and topple over the verge – The verge of what? We wondered. Was it like a cliff?”. Daisy holds no truck with victim-blaming. She was smuggled into Canada as a baby and raised by adoptive parents Melanie and Neil (who are killed by a Gilead car bomb fairly early on).

Aunt Lydia is writing up her memoirs in a dark corner of the Hildegard Library, of Ardua Hall (where future Aunts are trained). She recounts how she survived the initial coup and made her way up the ranks, but very early on she subverts her previous image from The Handmaid’s Tale and reveals her aim to bring the regime down from within. It is she who has been helping Mayday with smuggled microdot escape routes and maps – but she also has something bigger planned. “Having tunnelled this far under the foundations of Gilead with my stash of cordite, might I falter?”, she asks as the novel picks up pace. “I would destroy these pages I have written so laboriously, and I would destroy you along with them, my future reader. One strike of a match and you’ll be gone – wiped away as if you had never been, as if you will never be”. Gilead is past, present, and future. Her text is a historical artefact which heralds and imagines what has been, and what may yet come to pass.

Sadly, the novel possesses a major structural flaw. Until very late in the book, there is nothing to indicate that Aunt Lydia’s chapters do not operate simultaneously with Agnes’s. Agnes’s and Jade’s testimonies are made with the benefit of retrospect, which can make time elastic in the telling, but that does not account for the temporal mismatch. Jade’s account takes place over a matter of weeks: she goes from being a normal teenager to her parents being killed in a car bomb and becoming a fugitive, to being trained by Mayday for their most significant mission to date; Aunt Lydia is informed of her progress in real time.

By contrast, Agnes is 13 at the novel’s opening. She attends school, where she is taught by Aunt Lydia’s associates. When one of her classmates, who cannot bear the prospect of getting married, slashes her wrists with a pair of secateurs in flower arranging class, Aunt Lydia offers to spare her by enrolling her at Ardua Hall. She does the same for Agnes. Casually, nine years elapse: Agnes is no longer an illiterate bride-to-be; she is Supplicant and almost ready for her missionary work as a “Pearl Girl”. It is at this point that her path crosses with Jade’s – but given the pacing of Jade’s storyline, and how both have been tracked by Aunt Lydia, this doesn’t make sense.

The Testaments lacks the slow, fine claustrophobia of The Handmaid’s Tale. The writing is rushed, with clichés patching the gaps to get us from one moment of reaction to another: “I knew his hug was acting, but at that moment I didn’t care. I really did feel almost as if he was my first boyfriend”, muses Jade. Most of it reads like bad YA fiction, written by someone unused to ventriloquising the young and who ultimately takes a dim view of their readership’s intelligence: “It was sickening to think one of them might have been planning to kill Melanie and Neil, even while they were eating the grapes and pieces of cheese.” When Jade, posing as a “street person”, is picked up by Pearl Girls, she bursts into tears, crying “There was violence at home!” as if she’s reciting something off the front of a waiting room brochure. When Agnes encounters shocking information, she states simply “I was bedazzled, as if struck by lightning”. The phrasing of a Particicution gets parroted across all three women: Aunt Lydia recounts two men “literally torn apart by seventy shrieking Handmaids”, Agnes watches “two men being literally ripped apart by Handmaids,” and Jade is shocked by “two men literally torn apart by a mob of frenzied women”. Even if the repetition casts doubt on the veracity of each woman’s eyewitness account, it is a blunt and boring authorial strategy. When Jade and Agnes end up in an inflatable boat, Jade seems to have leapfrogged out of an Americanised Fantastic Fivesnafu: “I am fucking sorry, but we are in a hot mess emergency right now! Now, grab the oar!”.

There are, however, moments of hilarity. Lydia, conversing with Commander Judd (“a great believer in the restorative powers of young women”), quips ‘“Not for nothing do we at Ardua Hall say ‘Pen Is Envy’”’. There is a degree of narratorial wink-wink when Aunt Lydia writes of an Aunt nervously wringing her hands, “I was ashamed of her for being so novelistic”. A discussion between the Gilean Becka and Jade about the etymology of “bucket list” occasions gallows humour:

“It’s from ‘kick the bucket’,” said Jade. “It’s just a saying”. Then, seeing our puzzled looks, she continued. “I think it’s from when they used to hang people from trees. They’d make them stand on a bucket and then hang them, and their feet would kick, and naturally they would kick the bucket. Just my guess.”

“That’s not how we hang people here,” Becka said.

Overall, the novel is a sharp rebuke to the world in which we have always lived, where female testimony is dismissed as apocryphal. The Testaments’s desired status as record takes precedence over narrative craft. As women’s invisibility from canonical history gains attention, it reveals a ferocious appetite for pseudo- and para-historical documents: where no one bothered to record women’s experiences, material will be made up, projected and imagined into the absences. If no foremothers can be found to light our way, they shall be invented. Atwood knows that fiction can have more power than fact in spreading ideas and precedents. She concludes: “A bird of the air shall carry the voice, and that which hath wings shall tell the matter.”

- The Testaments by Margaret Atwood published by Chatto & Windus hardback £20

- Read more books reviews on theartsdesk

Add comment