Every now and then a book comes out that can change lives. If a survey like this had appeared when I was a student at the Slade, the struggle to make headway as a female artist would have seemed less daunting. We’d have had role models and names with which to counter the assertion that there had never been any significant women artists. And the recent explosion of female talent celebrated in this book might have happened a generation earlier.

Phaidon’s latest offering is a revelation. The title is a response to the essay “Why Have There Been No Great Woman Artists?” written in 1971 by American art historian Linda Nochlin. She argued that, because they were excluded from the institutions that educated and promoted artists, women were prevented from even entering the fray. “The fault lies”, she wrote, “not in our stars, our hormones, our menstrual cycles, or our empty internal spaces, but in our institutions and our education.”

This impressive survey spans 500 years. Arranged alphabetically, over 400 artists are represented by a single, well chosen image and a paragraph summarising their life and achievements. It’s incredibly hard to distill a life’s work into a few hundred words, but these 23 writers do an excellent job of summarising the salient points. Given Nochlin’s thesis, the biggest surprise is the number of women who managed to excel throughout history, especially in places like Renaissance Italy and seventeenth century Holland where the arts were flourishing. So why don’t we know more about them? Most have been written out of art history and their works lost or attributed to more famous male colleagues.

This impressive survey spans 500 years. Arranged alphabetically, over 400 artists are represented by a single, well chosen image and a paragraph summarising their life and achievements. It’s incredibly hard to distill a life’s work into a few hundred words, but these 23 writers do an excellent job of summarising the salient points. Given Nochlin’s thesis, the biggest surprise is the number of women who managed to excel throughout history, especially in places like Renaissance Italy and seventeenth century Holland where the arts were flourishing. So why don’t we know more about them? Most have been written out of art history and their works lost or attributed to more famous male colleagues.

The earliest artist mentioned is Properzia de’ Rossi, an Italian sculptor born in 1490. The only woman to be cited by Giorgio Vasari in his art historical treatise of 1550, she made carvings from fruit stones which he describes as “marvellous to behold.… not only for the subtlety of the work, but also for the liveliness of the little figures.” Here she is represented by a marble relief commissioned for the facade of the Basilica di San Petronio in Bologna, one of the few works now attributed to her.

This is a story repeated over and over again. In the second edition, Vasari cites Plautilla Nelli whose paintings were so popular and so numerous in Florence “that it would be tedious to mention them all.” Yet today only four of her works can be identified for certain. A similar fate befell Dutch painter Judith Leyster. After her death in 1660, her paintings were frequently attributed to men such as Frans Hals. The reason? Money! When Leyster’s monogram was found on The Merry Company,1630 beneath Hals’ forged signature, the buyer sued for compensation on the grounds that he’d been sold a “worthless” copy !

Discrepancies in value still persist today. In 2014, Georgia O’Keeffe’s Jimson Weed, 1932 fetched $44.4m, the highest auction price for a work by a woman compared with $300m for a painting by de Kooning. Prices for living artists follow a similar pattern. In 2018, David Hockney’s Portrait of an Artist,1972 achieved $80m while Jenny Saville’s female nude Propped, 1992 fetched $12.

Discrepancies in value still persist today. In 2014, Georgia O’Keeffe’s Jimson Weed, 1932 fetched $44.4m, the highest auction price for a work by a woman compared with $300m for a painting by de Kooning. Prices for living artists follow a similar pattern. In 2018, David Hockney’s Portrait of an Artist,1972 achieved $80m while Jenny Saville’s female nude Propped, 1992 fetched $12.

Nelli acquired her amazing skills by studying the paintings of established masters such as Andrea del Sarto. Elisabetta Sirani was lucky enough to be trained by her father Giovanni. She took over his studio in Bologna at the age of 16 and became the family’s chief breadwinner, producing 200 paintings before her untimely death in 1665 aged only 27. Such was her fame that she was given a lavish public funeral; so much for the myth that there have been no major women artists!

Rosa Bonheur was denied access to life drawing classes, so she frequented the abattoirs of Paris and began painting animals. In 1865 she was the first woman to receive the Légion d”Honneur and the Empress Eugénie was moved to declare that “genius has no sex.” If lack of education and promotion were hurdles that had somehow to be overcome, the demands of pregnancy, birth and child rearing could prove insurmountable. Judith Leyster gave up her career at 27, for instance, to look after her five children.

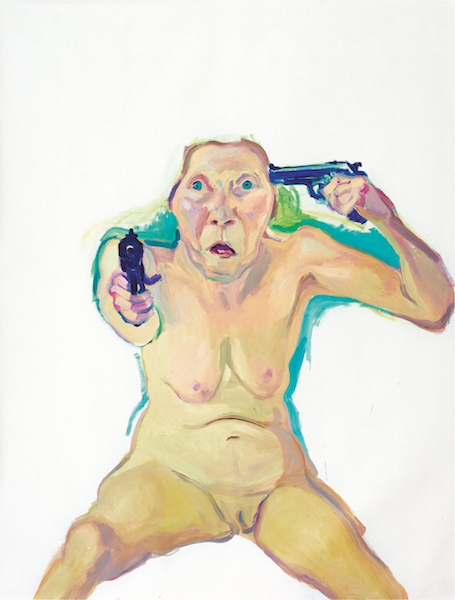

Recent generations have enjoyed the advantages of an education and choice when it came to child bearing, yet only the most resilient have been able to sustain their practice long enough to gain recognition. Phillida Barlow was largely ignored until she was 65; then in 2017 she was chosen to represent Britain at the Venice Biennale and her sculptures are now exhibited in museums the world over. Maria Lassnig had to wait until she was 94 to represent Austria at the Venice Biennale of 1913 when, belatedly, she was awarded the Golden Lion for lifetime achievement. (pictured below right: You Or Me, 2005)

Thankfully, prospects have improved immeasurably over the last thirty years and the burgeoning numbers of women now making and exhibiting work is reflected in this selection. Most impressive is the quality and diversity of work that includes performance, video, photography and installations (main picture) alongside painting and sculpture (pictured above left: Concert for Anarchy, 1990 by Rebecca Horn). Congratulations are due to Karen Wright for compiling the initial list of 2000 artists and whittling it down to a manageable number. Her choices are excellent; I can only think of three artists – Fiona Rae, Hellen van Meene and Shelagh Wakely – whom I would have added.

Thankfully, prospects have improved immeasurably over the last thirty years and the burgeoning numbers of women now making and exhibiting work is reflected in this selection. Most impressive is the quality and diversity of work that includes performance, video, photography and installations (main picture) alongside painting and sculpture (pictured above left: Concert for Anarchy, 1990 by Rebecca Horn). Congratulations are due to Karen Wright for compiling the initial list of 2000 artists and whittling it down to a manageable number. Her choices are excellent; I can only think of three artists – Fiona Rae, Hellen van Meene and Shelagh Wakely – whom I would have added.

This inspiring book is not just a celebration of women’s creativity, it is symptomatic of a sea change. Prejudices are melting away and museums are making efforts to reinstate the women erased from art history by unearthing their long forgotten and reattributed works. In 2017, for instance, Florence’s Uffizi Gallery inaugurated a series of shows of women artists with an exhibition dedicated to Plautilla Nelli. Last year the Flemish still life painter, Clara Peeters became the first woman ever to have a show at the Prado in Madrid and, next year London’s National Gallery will mount a solo show of the Baroque painter Artemisia Gentileschi – the first woman in its 200 year history to be accorded a retrospective.

Things they are achanging – at last. And if anyone has the temerity ever again to claim there have been no great women artists, you will be able to use this timely tome to knock the idea on its head, once and for all.

- Great Women Artists is published by Phaidon, £39.95

- Read more book reviews on theartsdesk

Add comment