Bette Howland: Blue in Chicago review – the city on trial, with the writer as witness | reviews, news & interviews

Bette Howland: Blue in Chicago review – the city on trial, with the writer as witness

Bette Howland: Blue in Chicago review – the city on trial, with the writer as witness

Short stories with a terrifying talent for the damning summing up

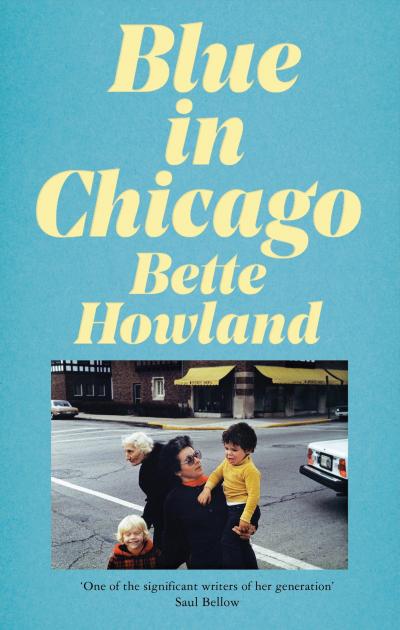

You feel at times, while reading the collection Blue in Chicago, that Bette Howland might have missed her vocation. In another life, Howland – until recently almost completely lost to literary history – could have made a name for herself as a distinctly unnerving judge; one feared by criminals and lawyers alike. She has a terrifying talent for the damning sum-up.

Exhibit A (on her cousin and her uncle): “After seven years of a sacrificially expensive university education, Gary will be earning about the same money as Rudy – a city of Chicago patrolman, a 'pig,' who had to be trundled through high school in a wheelbarrow.”

Exhibit B (on her New England in-laws): “The fact is, my in-laws were tight. Not the scraping, face-saving, working-class thrift I was used to; they were flagrantly, shamelessly stingy. The virtue of the faded WASP aristocracy.”

As these show, Howland had no trouble slapping a hard sentence or two on her “loved ones” – who, according to a couple of accounts, were not too bothered about what had been written about them. Her statements on their behaviour and appearance (for Howland, as for Balzac, the outer expresses the inner) go off with such a click, have such a ring of finality – seem, in other words, so right – that perhaps even they felt like justice had been done. Something which Howland was clearly preoccupied with, and daunted by: this selection of 11 stories is, sadly, about half of her total output.

As these show, Howland had no trouble slapping a hard sentence or two on her “loved ones” – who, according to a couple of accounts, were not too bothered about what had been written about them. Her statements on their behaviour and appearance (for Howland, as for Balzac, the outer expresses the inner) go off with such a click, have such a ring of finality – seem, in other words, so right – that perhaps even they felt like justice had been done. Something which Howland was clearly preoccupied with, and daunted by: this selection of 11 stories is, sadly, about half of her total output.

The fact that Howland produced so little, that she found herself so often within the shadow of doubt, suggests the stakes were more personal for her than any notion of just “doing justice”. As she comments herself, “there is nothing sensational about a courtroom”. There is something sensational about Howland’s style, however. She advances, she retreats, she worries, she teases, she splits hairs, she thinks on her feet. Less like a judge and more like an attorney in a primetime legal drama, one with skin in the game. More than that: one fighting her own corner, in propria persona. Only two of these stories are in the third person, and only one – “Aronesti”, a poignant, twilit tale about a young grieving widower – wrestles free from her biography.

But while Howland always seems ready for a good war of words, she also always has at least one eye on the jury (audience) and what they might think. In “Power Failure” – her metaphor for lost, failing or otherwise faulty connections between people; how they can go off the grid (Howland divorced young) – the narrator has a recurring dream about the daughter-she-never-had, reflecting on her own strained relationship with her mother. But before describing it, she breaks off. “Now please. Don’t get me wrong... I get discouraged myself, when people start talking about their dreams,” she writes. “Because what’s to keep us from telling lies? Making it all up?,” she asks, with characteristic wavering over questions of fiction and non-fiction. She is keen to reassure us. “This isn’t really a story – and I was dreaming. And I’d just like to see if I can get things straight.” So maybe there is something personal about doing justice after all.

Of course, the personal is political. The bulk of Blue in Chicago is a series of heavily autobiographical short stories or sketches (Howland herself demurred about what to call them) which chronicle (another label she rejected) a short period of her family’s history, but the backdrop of the city gets as much attention as the autobiography. Just as Nelson Algren, another neglected Chicago-based writer, was considered a sort of “bard of the down-and-outer”, Howland spends her time registering all the city’s waifs and strays. The chapter “Public Facilities”, based on her time working behind the desk at a public library, visited exclusively by the sick and the elderly – people “who have no place to go” – is one of the most closely observed and affecting in the book. This is Howland as expert witness, and it is the city that is on trial.

Her record of inner city blues can feel depressingly timely at a time like this. In the middle of this suite is “Twenty-Sixth and California”, a sort of artist’s impression of Chicago’s criminal courts and its parade of white lawyers and black felons. Nothing changes. The best and worst of the city seems condensed here: its “racial warfare” and corruption, crackling wit and style. “All their drama was in their dress,” Howland notes, shocked and delighted. It is perhaps the only place where all the parts of the city mingle and mix. Chicago is “a partitioned city, walled and wired”. A war zone with its own refugees: a “city of migrations” – defined by "white flight" out of the West Side in the mid-fifties. Sometimes, thanks to years of neglect and decay, hardly a city at all, “just the raw materials for a city”. She notices grass pushing through the concrete: “The prairie is always reasserting itself, pressing its claims.” The outer expressed in the inner.

Howland traverses these boundaries as she traces them. At one point, she escapes, summering in the nearby Indiana countryside, only to find a different sort of oppression: “the tyranny, the tyranny of these dreams of peace and quiet”. At another point, we join her on her regular bus ride through the working-class, mostly black and ethnic “South Side slums” to her student digs, from her family’s home in the more well-to-do, mostly white North Side suburbs. She spends the whole journey with a copy of The People Shall Judge open on her lap. So perhaps this is the real Howland: woman of the people, the onlooker, one of the crowd. There is, after all, nothing haughty about Howland. Perhaps one reason why her modest short fiction is only just being (re)placed alongside other American, Jewish writers who also scrutinised Chicago, such as Philip Roth and Saul Bellow (with whom she had a brief affair and longer correspondence).

The fate of female careers and legacies within man-made institutions, such as literary canons, is the sort of buried narrative in the final piece in the collection, the novella-length Calm Sea and Prosperous Voyage, which really should have been enough to clinch Howland some literary fame alone. In a sort of rambling diary format, a nameless narrator tells the final days of Victor Lazarus, supposedly the “Best Philosopher of His Generation”, despite a dwindling output, a serious drinking problem and several bouts of illness which, true to his name, he kept bouncing back from.

His final fling, yet acting like his next of kin, she wonders about her role in his story – “Who was I? Where did I fit in?” – as well as her own. We find out she is a fairly accomplished academic herself – with more credentials, but half the recognition – and she litters her account with literary, philosophical, rabbinical asides as if to prove it. She settles on the humble status of “witness at the scene”. But in truth, as she spars with her half-hearted lover beyond the grave, she emerges as prosecutor, defendant, key witness and fly-on-the-wall all at the same time. And PI, to boot; putting together the pieces, reconstructing events. There’s a hint of Raymond Chandler in Howland. And more than a touch of Virginia Woolf’s Jacob’s Room in her Calm Sea.

Like that novel, her novella, which has also been called experimental (although Howland refused to call it anything in particular), has a hole where the protagonist should be, covered up by a patchwork of testimonies from the absent character’s inner circle. In the end, this is how you know that Howland, a lifelong outsider, has not missed her vocation at all. In this, her magnum opus (in more than size alone), she shows off her talent, her relish, for filling in the gaps; making up the lack; making it all up. Writing against loss, against failure, she proves herself a writer through and through.

- Blue in Chicago by Bette Howland (Picador, £12.99)

- Read more book reviews on theartsdesk

rating

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Books

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Natalia Ginzburg: The City and the House review - a dying art

Dick Davis renders this analogue love-letter in polyphonic English

Natalia Ginzburg: The City and the House review - a dying art

Dick Davis renders this analogue love-letter in polyphonic English

Tom Raworth: Cancer review - truthfulness

A 'lost' book reconfirms Raworth’s legacy as one of the great lyric poets

Tom Raworth: Cancer review - truthfulness

A 'lost' book reconfirms Raworth’s legacy as one of the great lyric poets

Ian Leslie: John and Paul - A Love Story in Songs review - help!

Ian Leslie loses himself in amateur psychology, and fatally misreads The Beatles

Ian Leslie: John and Paul - A Love Story in Songs review - help!

Ian Leslie loses himself in amateur psychology, and fatally misreads The Beatles

Samuel Arbesman: The Magic of Code review - the spark ages

A wide-eyed take on our digital world can’t quite dispel the dangers

Samuel Arbesman: The Magic of Code review - the spark ages

A wide-eyed take on our digital world can’t quite dispel the dangers

Zsuzsanna Gahse: Mountainish review - seeking refuge

Notes on danger and dialogue in the shadow of the Swiss Alps

Zsuzsanna Gahse: Mountainish review - seeking refuge

Notes on danger and dialogue in the shadow of the Swiss Alps

Patrick McGilligan: Woody Allen - A Travesty of a Mockery of a Sham review - New York stories

Fair-minded Woody Allen biography covers all bases

Patrick McGilligan: Woody Allen - A Travesty of a Mockery of a Sham review - New York stories

Fair-minded Woody Allen biography covers all bases

Howard Amos: Russia Starts Here review - East meets West, via the Pskov region

A journalist looks beyond borders in this searching account of the Russian mind

Howard Amos: Russia Starts Here review - East meets West, via the Pskov region

A journalist looks beyond borders in this searching account of the Russian mind

Henry Gee: The Decline and Fall of the Human Empire - Why Our Species is on the Edge of Extinction review - survival instincts

A science writer looks to the stars for a way to dodge our impending doom

Henry Gee: The Decline and Fall of the Human Empire - Why Our Species is on the Edge of Extinction review - survival instincts

A science writer looks to the stars for a way to dodge our impending doom

Jonathan Buckley: One Boat review - a shore thing

Buckley’s 13th novel is a powerful reflection on intimacy and grief

Jonathan Buckley: One Boat review - a shore thing

Buckley’s 13th novel is a powerful reflection on intimacy and grief

Help to give theartsdesk a future!

Support our GoFundMe appeal

Help to give theartsdesk a future!

Support our GoFundMe appeal

Jessica Duchen: Myra Hess - National Treasure review - well-told life of a pioneering musician

Biography of the groundbreaking British pianist who was a hero of the Blitz

Jessica Duchen: Myra Hess - National Treasure review - well-told life of a pioneering musician

Biography of the groundbreaking British pianist who was a hero of the Blitz

Add comment