“Duck! Here comes another year.” We can, I think, all empathise with the motions and emotions of Ogden Nash’s new year poem, “Good Riddance, But Now What?” Before, however, we bid a troublesome year farewell, we look back at the year in fiction and share our favourites. 2021 was the year that Sally Rooney, to high anticipation, published her third novel, that Damon Galgut (third time lucky) won the Booker, and that Hillary Clinton, continuing the family legacy, wrote a thriller. Read on for more.

The best novel I read this year was without doubt Jon McGregor’s Lean Fall Stand (Fourth Estate, £14.99), which I have recommended, leant and given away so many times that it’s time I bought a third copy. The three-word title corresponds to the novel’s three-part structure and accompanying shifts in point-of-view: Lean presents us with an accident on a mapping expedition to Antarctica during which technical assistant Doc Wright suffers a stroke which robs him of his ability to communicate through speech; Fall narrates the weeks and months following Doc’s return to Cambridge through the eyes of his wife Anna, whose life is so overtaken by the drudgery of care that her own relationship with language begins to break down too; in Stand, we observe Doc and Anna’s visits to a Cambridge aphasia support group, where a cast of diversely impaired stroke survivors meet to practise speaking and to be listened to. It is as meticulously researched and intricately composed as we might expect from McGregor: he travelled to Antarctica as a fellow of an Arts Council-supported artists’ programme by the British Antarctic Survey and his acknowledgements section warmly thanks the Aphasia Nottingham self-help group, where he was a “regular guest”.

The best novel I read this year was without doubt Jon McGregor’s Lean Fall Stand (Fourth Estate, £14.99), which I have recommended, leant and given away so many times that it’s time I bought a third copy. The three-word title corresponds to the novel’s three-part structure and accompanying shifts in point-of-view: Lean presents us with an accident on a mapping expedition to Antarctica during which technical assistant Doc Wright suffers a stroke which robs him of his ability to communicate through speech; Fall narrates the weeks and months following Doc’s return to Cambridge through the eyes of his wife Anna, whose life is so overtaken by the drudgery of care that her own relationship with language begins to break down too; in Stand, we observe Doc and Anna’s visits to a Cambridge aphasia support group, where a cast of diversely impaired stroke survivors meet to practise speaking and to be listened to. It is as meticulously researched and intricately composed as we might expect from McGregor: he travelled to Antarctica as a fellow of an Arts Council-supported artists’ programme by the British Antarctic Survey and his acknowledgements section warmly thanks the Aphasia Nottingham self-help group, where he was a “regular guest”.

McGregor’s status as one of the greatest prose stylists writing today was cemented by his earlier novels, but here he turns that style to the truly remarkable ends of conveying through language what it means and feels like to lose your grip on language. The resulting prose is elastic, at times Joycean in its lyricism and at times as vividly realist as a Victorian novel, bending and moulding itself to the character, situation and feeling at hand. Lean Fall Stand lets its characters speak for themselves and invites us in to listen on their terms. It is a novel of profound and deliberate empathy. Lizzie Hibbert

“There is too much past, and everyone knows it,” laments the Russian poet and essayist Maria Stepanova. No one can any longer write, or read, a family chronicle – even one, like hers, that sweeps across the tragic landscapes of 20th-century history from Revolution to Purge to Holocaust to Cold War and beyond – as if we don’t know the score. So how can she avoid kitsch, pastiche or nostalgia as she strives to do justice to her forebears and their struggle, as Russian Jews, to live, love and thrive in the face of history’s endless storms? In Memory of Memory (Fitzcarraldo Editions, £14.99) is her answer, and it is a triumph: an intimate, lyrical, gently learned, blend of research, reminiscence and reflection, flecked with recreations of people and events that dance on the brink of fiction. Translated with tenderness and eloquence by Sasha Dugdale, this is a wise, beautiful but warmly companionable memoir-cum-history. It honours both the ghosts who inhabit it, and the literary art of memory itself. Boyd Tonkin

“There is too much past, and everyone knows it,” laments the Russian poet and essayist Maria Stepanova. No one can any longer write, or read, a family chronicle – even one, like hers, that sweeps across the tragic landscapes of 20th-century history from Revolution to Purge to Holocaust to Cold War and beyond – as if we don’t know the score. So how can she avoid kitsch, pastiche or nostalgia as she strives to do justice to her forebears and their struggle, as Russian Jews, to live, love and thrive in the face of history’s endless storms? In Memory of Memory (Fitzcarraldo Editions, £14.99) is her answer, and it is a triumph: an intimate, lyrical, gently learned, blend of research, reminiscence and reflection, flecked with recreations of people and events that dance on the brink of fiction. Translated with tenderness and eloquence by Sasha Dugdale, this is a wise, beautiful but warmly companionable memoir-cum-history. It honours both the ghosts who inhabit it, and the literary art of memory itself. Boyd Tonkin

“No one writes in praise of giving up, any more than people write in celebration of shame”, the essayist Adam Phillips wrote recently. “The question I want to broach is not why do we give up, but why don’t we?” Another writer who chose to pose that troubling question earlier this year was Natasha Brown, whose small but mighty debut Assembly (Penguin, £8.99) arrived at the end of an 18-month period that had challenged our need (and/or desire) to keep calm and carry on as we had before. Her book follows a high-flying Black British woman who, after a life-changing diagnosis, decides to take the opportunity to take apart everything she has built and examine all the little pieces that reflect the state of the nation, her place in it and much else besides. Brown hardly puts a word out of place as she swerves from fiction to social criticism and includes no more than she needs to. That restraint can sometimes make Assembly feel like a bit of a blueprint for a more substantial novel, but I can’t think of one that has left a deeper impression or made me as intrigued to see what a writer will do next – if she doesn’t fully embrace the virtues of coming to a full stop, that is. Daniel Lewis

“No one writes in praise of giving up, any more than people write in celebration of shame”, the essayist Adam Phillips wrote recently. “The question I want to broach is not why do we give up, but why don’t we?” Another writer who chose to pose that troubling question earlier this year was Natasha Brown, whose small but mighty debut Assembly (Penguin, £8.99) arrived at the end of an 18-month period that had challenged our need (and/or desire) to keep calm and carry on as we had before. Her book follows a high-flying Black British woman who, after a life-changing diagnosis, decides to take the opportunity to take apart everything she has built and examine all the little pieces that reflect the state of the nation, her place in it and much else besides. Brown hardly puts a word out of place as she swerves from fiction to social criticism and includes no more than she needs to. That restraint can sometimes make Assembly feel like a bit of a blueprint for a more substantial novel, but I can’t think of one that has left a deeper impression or made me as intrigued to see what a writer will do next – if she doesn’t fully embrace the virtues of coming to a full stop, that is. Daniel Lewis

“Tiny human ears strewn about the table like rose petals.” A “baby, falling to the bottom of a well, where it melts like a cube of sugar”. The churchyard “glutted with the last fallen leaves, shades of leathery brown and livid yellow, the earth turning up a leprous cheek”. A K Blakemore’s debut The Manningtree Witches (Granta, £12.99) presents a fictionalised account of the English witch trials during the English Civil War with dark, mesmerising exactness. Built from the testimonies of women hunted by the Witchfinder General Matthew Hopkins during the English Civil War, the book hovers through the fog and filthy air of Manningtree and Mistley, two small towns where “peculiar” women are the all-too-easy subject of suspicion, and are blamed and condemned. It’s a brilliant paean to those who have “gone voiceless, or else been muted by victimhood” as a result of the patriarchal persecution of women, and the book announces its debt to Silvia Federici in its afterword. Earlier this year, it won the Desmond Elliott Prize. Jess Payn

“Tiny human ears strewn about the table like rose petals.” A “baby, falling to the bottom of a well, where it melts like a cube of sugar”. The churchyard “glutted with the last fallen leaves, shades of leathery brown and livid yellow, the earth turning up a leprous cheek”. A K Blakemore’s debut The Manningtree Witches (Granta, £12.99) presents a fictionalised account of the English witch trials during the English Civil War with dark, mesmerising exactness. Built from the testimonies of women hunted by the Witchfinder General Matthew Hopkins during the English Civil War, the book hovers through the fog and filthy air of Manningtree and Mistley, two small towns where “peculiar” women are the all-too-easy subject of suspicion, and are blamed and condemned. It’s a brilliant paean to those who have “gone voiceless, or else been muted by victimhood” as a result of the patriarchal persecution of women, and the book announces its debt to Silvia Federici in its afterword. Earlier this year, it won the Desmond Elliott Prize. Jess Payn

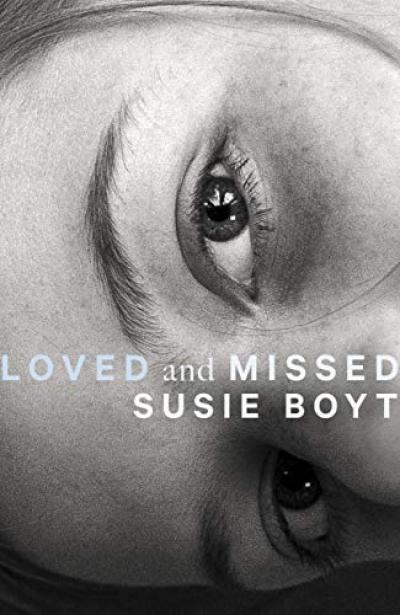

After finishing Susie Boyt’s Loved and Missed (Virago, £16.99) I was compelled to read it again, already loving and missing it so much. Ruth, a school-teacher, is a single mother to Eleanor, a chaotic, icy heroin addict in her twenties who has just given birth to Lily. After the christening, Ruth manages to rescue the baby – Eleanor and her partner don’t put up much resistance – and we see their stable, loving life together unfold in Ruth’s cosy north London flat. Lily is a joy and Eleanor is an intermittent, unbalancing presence. Boyt delves deep, with a marvellously light touch, into the intricacies of this troubled family dynamic, where Ruth’s love for her daughter and granddaughter is a steadfast force. Markie Robson-Scott

After finishing Susie Boyt’s Loved and Missed (Virago, £16.99) I was compelled to read it again, already loving and missing it so much. Ruth, a school-teacher, is a single mother to Eleanor, a chaotic, icy heroin addict in her twenties who has just given birth to Lily. After the christening, Ruth manages to rescue the baby – Eleanor and her partner don’t put up much resistance – and we see their stable, loving life together unfold in Ruth’s cosy north London flat. Lily is a joy and Eleanor is an intermittent, unbalancing presence. Boyt delves deep, with a marvellously light touch, into the intricacies of this troubled family dynamic, where Ruth’s love for her daughter and granddaughter is a steadfast force. Markie Robson-Scott

Caleb Azumah Nelson’s debut Open Water (Viking, £8.99) is a gritty yet enchanting tale of a young man trying to discover his authentic self. It is a defiant love letter to Black British culture that explores how artistic expression and profound romantic love can temporarily relieve feelings of powerlessness in Black lives. The novel was one of the most poetic pieces of fiction that I’ve read in years. Izzy Smith

Add comment