Georg Baselitz, the veteran German artist who likes to bait, provoke and raise hackles, most recently with an interview in Der Spiegel in which he said women artists couldn’t paint (he mentioned the few exceptions, which was generous of him), is enjoying a triple billing in London.

His new paintings at the Gagosian Gallery adopt the Abstract Expressionist brushstrokes and bright palette of Willem de Kooning, while the British Museum displays prints from the early Sixties and Seventies, alongside the graphic works of five postwar German contemporaries. The third outing opens this week at the Royal Academy with a selection of 16th-century Renaissance and Mannerist chiaroscuro woodcuts from Baselitz’s personal collection, a collection that’s had some influence on the artist’s own style and printmaking technique.

Baselitz’s unique method of training our gaze may still be seen by many to be little more than a gimmick

The Gagosian’s display, Farewell Bill, is part de Kooning homage, part wildly witty riff. Due to the hugeness of the paintings, it takes a while to see how the loose, fat brushstrokes in each of the 15 canvases coalesce to form an upside-down head, true to Baselitz’s signature inversions. Though they’re easier to see in reproduction, you won’t necessarily detect these sad-eyed, cartoonish heads when you’re up close to the real paintings – unless of course you’ve read about them beforehand – so this actually feels a bit like a spoiler.

Part of the original point of adopting his inversions was to allow the viewer to see the paintings as a dynamic surface of marks rather than as merely descriptive. In other words, to present them as paintings, in which formal relationships are played out, rather than illustrative pictures. This was a time, in the late Sixties, when abstract painting was still the dominant force in Europe.

But Baselitz is also an artist deeply rooted in German experience. And as for his figure inversions, however effective it was as an initial means of getting the viewer to concentrate on gesture and surface, doesn’t mean it won't eventually fall into the trap of appearing gimmicky. It does. But I’ve come to think that this, too, is part of Baselitz’s complex relationship to his work. It’s deeply serious, yet aggressively mocking. It’s mock-heroic, yet emotionally fraught. It’s heavy with the weight of history, yet, unlike the work of Anselm Kiefer, it’s lightened by tremendous wit. One looks at a Baselitz and finds all those oppositions and more – and none no more so than that between abstraction and figuration.

The Farewell Bill paintings – even the title of the exhibition is comic-book jokey, yet guilelessly tender – are, in fact, self-portraits. They are rather gormless, goonish, blank-eyed self-portraits in which Baselitz is seen in a white baseball cap bearing the slogan Zero. He has told the story of how he once went into a shop and noticed a baseball cap with the word Zero on it and was rather taken by that. Zero happens also to be the name of his paint supplier, while the phrase "Zero Hour" (Stunde Null) marks the immediate aftermath of Germany’s capitulation in the Second World War.

But whatever the genesis of the Zero of the paintings, it also suggests that they may even be read as a kind of memento mori – not just a belated farewell to a spiritual mentor but a self-reflective meditation on the artist’s own death. The presence of the artist buried beneath the jaunty chaos of paint becomes itself a metaphor.

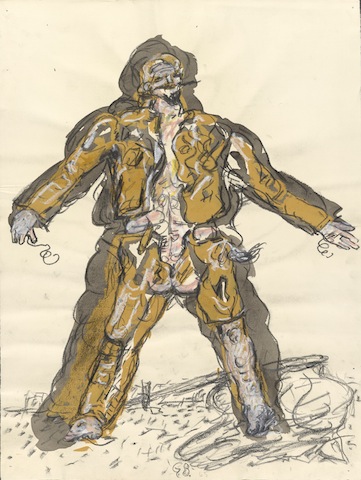

At the Print Rooms of the British Museum there are two related exhibitions. The first is a room containing works on paper by Baselitz alongside those of Gerhard Richter, Blinky Palermo, Markus Lüperz, AR Penck and Sigmar Polke, each an East German who crossed the border to make a life and career for himself, while the second room focuses on works by Baselitz alone. Here one gets a deeper sense of Baselitz as a German artist, particularly through his ironically named series “Heroes” (also called A New Type) of drawings and woodcuts – a print medium associated in Western art with German artists and a more expressive, “primitivist” tendency – of the mid-Sixties.

At the Print Rooms of the British Museum there are two related exhibitions. The first is a room containing works on paper by Baselitz alongside those of Gerhard Richter, Blinky Palermo, Markus Lüperz, AR Penck and Sigmar Polke, each an East German who crossed the border to make a life and career for himself, while the second room focuses on works by Baselitz alone. Here one gets a deeper sense of Baselitz as a German artist, particularly through his ironically named series “Heroes” (also called A New Type) of drawings and woodcuts – a print medium associated in Western art with German artists and a more expressive, “primitivist” tendency – of the mid-Sixties.

We encounter the lone, distorted figure of the German soldier in a devastated landscape. (Pictured above left: Partisan, 1965). He is seen falling, his outstretched arms rigid and elongated. Or else he is mutilated, and in one drawing he’s apparently masturbating. Other drawings depict farm animals that resemble Northern Renaissance sketches and here we find tethered oxen and dogs strung up by their hind legs.

There is one monstrous yet clearly pathetic creature who appears to be half man, half slug, with its slug’s head bent in sorry abjection (pictured right: Untitled, 1965). Then there are jagged linocuts of eagles, that heraldic bird of the German Empire and of Nazi Germany. There’s one that’s barely decipherable, splattered on a flag the colours of the German Democratic Republic.

There is one monstrous yet clearly pathetic creature who appears to be half man, half slug, with its slug’s head bent in sorry abjection (pictured right: Untitled, 1965). Then there are jagged linocuts of eagles, that heraldic bird of the German Empire and of Nazi Germany. There’s one that’s barely decipherable, splattered on a flag the colours of the German Democratic Republic.

The 90 or so prints in this exhibition are from the private collection of Count Christian Duerckheim. Thirty-four have been given as a gift to the British Museum. These politically charged yet deeply personal works are a powerful addition to the museum’s graphic holdings.

- Georg Baselitz: Farewell Bill at the Gagosian until 29th March

- Germany Divided: Baselitz and his generation at the British Museum until 31 August

![SEX MONEY RACE RELIGION [2016] by Gilbert and George. Installation shot of Gilbert & George 21ST CENTURY PICTURES Hayward Gallery](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_125_x_125_/public/mastimages/Gilbert%20%26%20George_%2021ST%20CENTURY%20PICTURES.%20SEX%20MONEY%20RACE%20RELIGION%20%5B2016%5D.%20Photo_%20Mark%20Blower.%20Courtesy%20of%20the%20Gilbert%20%26%20George%20and%20the%20Hayward%20Gallery._0.jpg?itok=3oW-Y84i)

Add comment