When Complicite conceived their beautiful A Disappearing Number they gave maths energy, drama, and above all watchability, but they never quite brought the heart. In Simon Stephens’s new adaptation, A Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time has it in abundance (as well of course as a dead bee, a live rat, three beer cans and 20-odd metres of model train-track). When you can persuade an audience to stay behind after the curtain-call for a mini maths tutorial you’re doing something right; when you can reduce them to tears with it you’re doing something miraculous.

Christopher (Luke Treadaway) is 15 years, three months and two days old. His “behavioural problems” (author Mark Haddon regrets using the term Asperger Syndrome originally) keep him at a special school and at a distance from all but his immediate family. But when the neighbour’s dog is found murdered with a garden fork Christopher must push past his fears and investigate the crime. In so doing he uncovers secrets rather closer to home, travels to London, and sits his maths A-level.

Elliott’s chief victory here is her balancing of the polyphony of theatre with a production that has a very definite point of view

It’s a simple enough story, but in Mark Haddon’s vivid treatment became something of a cult novel. Like The Great Gatsby though it’s a book that’s all in the telling; Christopher’s assured, relentless logic colours everything, and to lose it would risk losing the story’s spirit. Rather than do a Gatz, Simon Stephens and director Marianne Elliott offer a much more directly theatrical experience, integrating Finn Ross’s video design and Ian Dickinson’s sound with physical theatre, music and straight narrative.

Christopher’s voice is preserved both in his own mouth but also (for the book’s monologue) in that of Siobhan (a glowing Niamh Cusack) his teaching assistant. Faithful to his source, Stephens’s sole innovation is a theatrical meta-frame that allows Christopher to step out of proceedings and direct or correct his ‘cast’ in this school-play adaptation of his own book. It’s a device that rings true (and often funny), particularly when we see the obsessive boy correcting the misremembered actions of others. Elliott’s chief victory here is her balancing of the polyphony of theatre with a production that has a very definite point of view. We see nothing, experience nothing except as Christopher himself sees it.

Bunny Christie’s ingenious design sets up the endlessly flexible Cottesloe in the round. Seats rise football-stadium-like around a central rectangle of graph paper – the geometric, quantifiable units into which Christopher must translate his bafflingly fluid life experiences. Everything on set is hard-edged and non-specific, all human detail stripped away from it. Houses emerge in Brecht-lite numbered squares, and kitchen tables are built out of boxes. All of which casts the few moments of magic in striking relief. A ceiling full of stars offers the simplest, but a train-set and a quivering cardboard box will defeat the sternest of viewers.

Bunny Christie’s ingenious design sets up the endlessly flexible Cottesloe in the round. Seats rise football-stadium-like around a central rectangle of graph paper – the geometric, quantifiable units into which Christopher must translate his bafflingly fluid life experiences. Everything on set is hard-edged and non-specific, all human detail stripped away from it. Houses emerge in Brecht-lite numbered squares, and kitchen tables are built out of boxes. All of which casts the few moments of magic in striking relief. A ceiling full of stars offers the simplest, but a train-set and a quivering cardboard box will defeat the sternest of viewers.

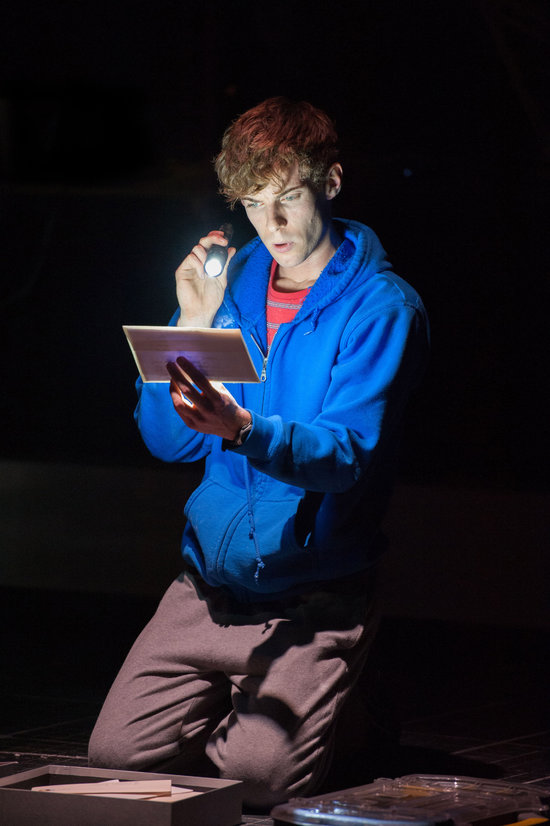

But for all the artistry of the production its greatest skill is in directing our focus to the cast. Treadaway (pictured above) dominates, never leaving the stage. His tense, twitching logic informs everything from the over-precise speech to the rigid body shapes, creating a boy who demands our sympathy even as we realise he wouldn’t understand or thank us for it. The violent clarity of Haddon’s prose finds natural expression in Treadway’s physicality, offset by the soft metaphors and kindness of Cusack’s Siobhan and Christopher’s mother (Nicola Walker).

There’s no shortage of comedy (a visual set-piece involving a train toilet is a highlight, as well as the interjections of Sophie Duval’s glib, bureaucrat of a headmistress and Una Stubbs's elderly neighbour) which helps the heartbreak slip down – so much so that you find yourself smiling even as the pain begins to pulse. At bottom this is a book about otherness, about the terrifying incomprehension, fear and suspicion we must all suppress in order to live our lives. We find ourselves in Christopher’s patient but short-tempered father (a beautifully understated Paul Ritter, pictured below with Treadaway) as he hits his son – the sole physical contact Christopher will permit, but also in Christopher himself as he shrieks and shies away from the touch.

In the train-rattle of dialogue and visuals a rare moment of stillness proves devastating. Finding Christopher traumatised and covered in vomit, his father must clean him up. His limp son hasn’t the strength to reject his help, and as Ed removes his soiled clothes we watch him permit himself the smallest of physical consolations – resting his lips against his son’s hair for just a moment.

In the train-rattle of dialogue and visuals a rare moment of stillness proves devastating. Finding Christopher traumatised and covered in vomit, his father must clean him up. His limp son hasn’t the strength to reject his help, and as Ed removes his soiled clothes we watch him permit himself the smallest of physical consolations – resting his lips against his son’s hair for just a moment.

The National Theatre’s website suggests the show for those of 13 years and over. But to my mind it could only safely be viewed by those 13 and under – young enough to take the jubilant delight in puzzles and numbers, the adventuring rites of passage, and skim the sadness. For those of a less tender age it’s a devastating joy of a show. You’ll leave wrung-out, but honestly so; there’s no sentimentality here, just sentiment by the squared hypotenuse.

Add comment