It’s only fitting that Sir John Eliot Gardiner should be celebrating his 70th birthday with a concert in the Royal Albert Hall. That it should be a nine-hour marathon of a concert is not only fitting, but entirely predictable for a musician who has always kept one eye on the next and biggest challenge.

Not for this conductor the familiar or the conventional, a career spent in the safe, sequestered world of early music. Over almost 50 years Gardiner has balanced choral pilgrimages with opera productions, has conducted symphony orchestras and period ensembles, has founded his own record label and shepherded his performing groups through some of the toughest economic years classical music has faced.

But still the challenges keep coming. This year alone will see Gardiner completing the epic cycle of Bach recordings he began back in 2000, publishing his major new Bach biography for Penguin and presenting a new BBC documentary on the composer – as well, of course, as masterminding the Royal Albert Hall Bach marathon which will combine his own Monteverdi Choir and Orchestra with soloists for performances that range from solo works for organ and violin to the composer’s epic B Minor Mass. Bach has been the touchstone, the constant, in a career of astonishing breadth and unpredictability. But why does the conductor always return to this music, and what comes next after this milestone celebration?

ALEXANDRA COGHLAN: You’ve said previously that you always come back to Bach at crucial junctures and milestones in your life - can you talk me through a few?

ALEXANDRA COGHLAN: You’ve said previously that you always come back to Bach at crucial junctures and milestones in your life - can you talk me through a few?

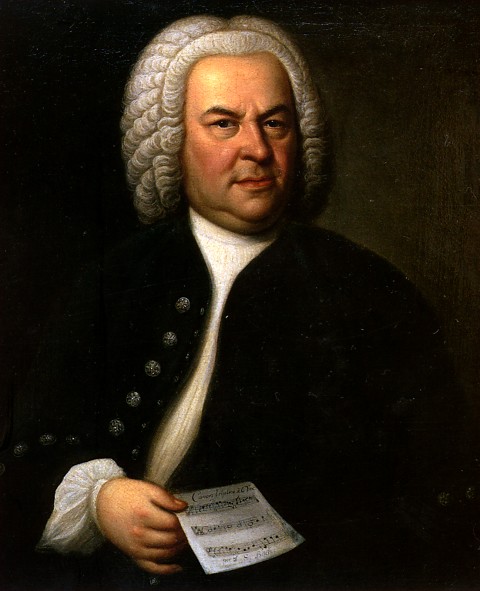

JOHN ELIOT GARDINER: It really all starts with that picture on the wall [a reproduction of Elias Gottlob Haussmann’s famous portrait of Bach]. It’s one of only two authenticated portraits, and the original hung in my parents’ house when I was born. They got it from a refugee, Walter, who arrived on a bicycle in Dorset in 1936 with a rucksack, a guitar and this picture as a canvas rolled up. He knew my dad and asked him to look after it for him. Our house had a very low ceiling, so as a little boy I looked directly into Bach’s eyes as he hung on the landing. I couldn’t make head or tail of it; I loved his music, but I couldn’t reconcile it with the portrait which is detached and slightly forbidding. I passed that portrait every day of my childhood at the time when I was first learning Bach’s motets as a treble. Singing those motets, which I love to this day more than any other music, was my first introduction to the music

Were you singing these motets in a church context?

No, I was singing them with my family and friends. My parents were keen amateur musicians and all through the war years they used to sing the Byrd four-part and five-part masses alternately on Sundays with friends to keep their spirits up. I was allowed to join them as a treble and that’s how I got to know the music. It wasn’t until I went away to school that I realised that not everybody did that, and not everybody knew the Bach motets. That seemed very odd to me. It wasn’t at all precious though; my dad was very much a working farmer and used to sing at the top of his voice on his horse or his tractor, and although he loved polyphonic music as well as folksong, music was there very much to punctuate the agricultural year and to celebrate. He got very cross with me when I decided to become a professional musician. He thought that it was a terrible sell-out and a corrupting thing. But he came round to it just before he died, thank goodness. I learned an awful lot from him about the function of music, and how important it is as a musician to take not only time to prepare but also time to reflect after you’ve done a performance. All of us go straight from one gig to another and it’s not very healthy, but that’s just the way the industry runs.

Is this reflection purely technical, or something broader?

Something broader. He saw the whole process of music as something that grows out of silence and goes back into silence. You need to be able to calibrate that process. It’s something that Nadia Boulanger taught me also, how you need to prepare yourself, how the intake of breath and how the upbeat is an invitation to play. Similarly the music needs space to rest, to create its own resonance. It’s something that I try very hard to practise.

Your Easter Monday concert will feature nine hours of Bach. I imagine choosing the repertoire was either the easiest or the hardest decision…

Yes, it was both. You start off thinking that it’s going to be the “best of” but that doesn’t work. You just end up with a surfeit of great music. I definitely wanted it to be related to the time of year though. Christ lag in Todesbanden is Bach’s first Easter cantata and really sums up the struggle between the forces of life and death, dark and light. It sums up and relives the spirit of Easter, the spirit of Lutheranism and the spirit of Bach better than anything else I know. We are starting with the motet Singet dem Herrn which is epic in every way. It’s a celebration of the dance in music without any instruments other than continuo. It shows what Bach can do away from the organ, and how he can construct a whole orchestra just out of consonants and the sounds of a choir functioning really well. It’s hugely exhilarating. The B Minor Mass goes without saying because it is the summation of Bach’s whole life’s work. It’s a piece in which he goes back to his earliest roots and uses some of the first music he ever composed.

Yes, it was both. You start off thinking that it’s going to be the “best of” but that doesn’t work. You just end up with a surfeit of great music. I definitely wanted it to be related to the time of year though. Christ lag in Todesbanden is Bach’s first Easter cantata and really sums up the struggle between the forces of life and death, dark and light. It sums up and relives the spirit of Easter, the spirit of Lutheranism and the spirit of Bach better than anything else I know. We are starting with the motet Singet dem Herrn which is epic in every way. It’s a celebration of the dance in music without any instruments other than continuo. It shows what Bach can do away from the organ, and how he can construct a whole orchestra just out of consonants and the sounds of a choir functioning really well. It’s hugely exhilarating. The B Minor Mass goes without saying because it is the summation of Bach’s whole life’s work. It’s a piece in which he goes back to his earliest roots and uses some of the first music he ever composed.

I wanted to leaven the bread with works that explore the same processes in different genres. The Chaconne from the D minor Violin Partita has extraordinary narrative. It requires the listener to fill in the gaps that can’t be encompassed by the violin bow. Bach hints at them in pointillist suggestions. The Goldberg Variations similarly are very narrative. Variations are another hugely important principle in Bach, and in their own way the Goldbergs are just as theologically pregnant as the cantatas and the Passions. There’s a lot hidden in the interstices of the music.

You first conducted the B Minor Mass decades ago. How will your 70th birthday performance differ from those early ones?

You first conducted the B Minor Mass decades ago. How will your 70th birthday performance differ from those early ones?

I first conducted the Mass at the Royal Albert Hall in a 1973 Prom, which had Janet Baker, Elly Ameling, Tom Allen and Alexander Young – wonderful English oratorio singers all – sitting up at the front in their frocks. It was very formalised and it felt like an oratorio. This time it won’t be like that at all; the solo singers will step out from the choir, and I hope that there will be fantastic complicity and reciprocity between choir and orchestra. One of the things that we strive for is to get the instruments to sing like the choir and the singers to function with the virtuosity of instruments, so there’s a tremendous amount of synergy and just huge life in the performance.

The B Minor Mass can potentially seem intimidating in its size and scope to listeners unfamiliar with it. How would you suggest people listen and encounter it?

Bring your ears and an openness of mind. You need to be open to the narrative rather than the doctrine. The whole piece, the way the Mass is constructed, tells a story and it’s a damn good one. It’s so beautifully adumbrated and told, you can be cushioned just by the sonic and harmonic beauty of the counterpoint. You don’t have to be a mathematician to calculate it, or a musician to understand it. But also you can, without any degree of complication, pick up on his joy of dance music. Almost every movement has a relationship to a dance form of one type or other, and that’s wonderfully seductive for me. It’s my job as a conductor to see that those are articulated so as not to be too swift, or too sluggish.

How do you plan to use the performing space of the RAH? Will you be doing unusual things with setup and performance?

I did a Late Night Prom a few years ago and we put four platforms in the arena and had the Prommers very close to us. That worked up to a point, except that the audience behaved in a rather odd way, and it was a bit like being in the monkey house in the zoo. I am all for breaking down unnecessary performing barriers, like having string players standing up to play if possible. I’ve just done it in the Gewandhaus which is the most traditional concert-hall in Europe, and they played very freely and much more soloistically as a result. In many ways the Royal Albert Hall is actually more flexible than the Barbican or the Royal Festival Hall. Yes it’s like looking down the wrong end of a telescope if you happen to be sitting on the other side of the space and it can be difficult to connect, but if you’re promming it’s great.

I did a Late Night Prom a few years ago and we put four platforms in the arena and had the Prommers very close to us. That worked up to a point, except that the audience behaved in a rather odd way, and it was a bit like being in the monkey house in the zoo. I am all for breaking down unnecessary performing barriers, like having string players standing up to play if possible. I’ve just done it in the Gewandhaus which is the most traditional concert-hall in Europe, and they played very freely and much more soloistically as a result. In many ways the Royal Albert Hall is actually more flexible than the Barbican or the Royal Festival Hall. Yes it’s like looking down the wrong end of a telescope if you happen to be sitting on the other side of the space and it can be difficult to connect, but if you’re promming it’s great.

You’ve spoken forcibly in the past about your dislike for concerts halls in London generally and the Barbican and Royal Festival Hall in particular. What should a concert hall be like and how should it change how an audience is experiencing a performance?

You’ve spoken forcibly in the past about your dislike for concerts halls in London generally and the Barbican and Royal Festival Hall in particular. What should a concert hall be like and how should it change how an audience is experiencing a performance?

Shape is critical. Nobody has come up with anything better than a shoebox; no one has come up with anything better than brick and wood. Man-made materials just don’t work. Look at how well the Snape Maltings works and how disastrous the Barbican and the Royal Festival Hall are. Everything in the Royal Festival Hall is remote, there’s no immediacy. I think also the way that musicians walk onstage and the way that they look at an audience and greet them (or don’t) has a big impact on the way audiences receive music. I don’t necessarily mean that every concert should have a little speech from the podium, but if you can break the ice, it helps. If you have something personal to say about the music you can break lots of unnecessary membranes of resistance. You’re allowed to laugh! Why should one have this ridiculous code of silence between movements - it’s absurd.

You’ve performed Bach all over the world in some very different contexts. Have there been any particular reactions that have surprised you?

Performing the B Minor Mass in Tokyo to an audience of Shinto Buddhists, then travelling down in the lift with a whole lot of Japanese ladies all saying, “Thank you so much, the angels came,” was very touching. Doing the St Matthew Passion for the very first time in 1985 in East Berlin in the GDR with soldiers in full uniform standing in the aisles with tears pouring down their faces was also very powerful, and very poignant.

Looking back over half a century of performances of Bach, have you come to any conclusions as to why you react the way you do to his music, why you keep going back to him?

When you are standing in front of a group of musicians and give an upbeat to a piece of Bach, whether it is the B Minor Mass or a Passion or cantata, you have to put yourself in a certain frame of mind or else it’s not going to work. I take my cue from something that Bach himself wrote in a bible commentary: “Whenever musicians come together with the right spirit of dedication and devotion there is grace available to them.” Some people can do it by prayer, but I do it through inhalation, just as one would in a yoga exercise. If you have some form of intake of breath that is actually cleansing and open, chances are it will unlock the door to what’s to follow. Bach fills whatever space you allow him to enter, but you have to open the door. Lutheranism is such a sensual religion, it’s not like Puritanism, it’s very much a religion of connection and reciprocity. All that very sexual imagery you get from the Song of Solomon which is brought into the pietistic wing of Lutheranism is something one probably associates more with southern Europe, with Spain and Italy, but it’s a thread that’s very much present in Bach. I think it’s something that everyone can latch onto.

Sir John Eliot Gardiner leads a nine-hour Bach Marathon at the Royal Albert Hall on Easter Monday broadcast live on BBC Radio 3. He presents Bach: A Passionate Life on Saturday 30 March on BBC Two as part of the BBC’s Baroque Spring. The final recording of Gardiner’s Bach Cantata Pilgrimage is released on SDG in April. Information and tickets at bachmarathon.com.

Add comment