There is a 1953 Volkswagen parked in the Great Court of the British Museum, and we are reminded that Hitler persuaded Frederick Porsche (who gave his name of course to a hideously expensive luxury automobile) to design a people’s car. The postwar economic miracle of the defeated Germany finally allowed the Beetle to go into mass production; 21 million of them in fact – the largest number of a single model ever produced, until its hugely successful run ended in 2003. Here is a neat paradox: how an idea of one of the monsters of history became a protagonist of effective technological advance indicating welcome populist prosperity.

This is the introduction to a highly contentious and hugely ambitious exhibition. Germany: Memories of a Nation features some 200 objects with a 600-year chronology, displayed in the difficult space of the circular gallery above the old Reading Room. The ambition is breathtaking: an attempt to tell the story, not of a nation (what a ludicrous subtitle) but rather an object-led narrative of the German-speaking peoples. Today, Germany’s boundaries are only 24-years-old, with the uniting of the German Democratic Republic (east) with the German Federal Republic (west) in 1990.

The anthology is, at one level, an extraordinary exercise in cultural diplomacy

2014 as the year for this show has a double significance: the centenary of the outbreak of World War I, and the 25th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall. And of course, unmentioned here, the 300th anniversary of the accession of the first of the Hanoverians, George I. As a country we have a deeply ambivalent view not only of German history but of Germany today at the heart of Europe, and its most successful country, economically and socially. Germany has thrived in the postwar period in ways that Britain has not. So the anthology is, at one level, an extraordinary exercise in cultural diplomacy.

And there is a context here, facilitated by the fact that two German-born curators, Sabrina Ben Aouicha and Clarissa von Spee, and a British one, the British Museum's Barrie cook, have been involved, under director Neil MacGregor's lead. MacGregor is a charismatic and persuasive museum director, a superb speaker, an unusually adept cultural politician. During his 14-year tenure he has overtly placed the British Museum on a fascinating trajectory. He has positioned the museum – of course both quantifiably and qualitatively one of the three or four greatest in the world – as the world museum, holding its collections in trust for the world as a whole.

This is a very useful point of view when thinking about reparations and returns, as the ongoing controversy about the Parthenon Marbles, legally acquired in so far as the legalities of the day went, centuries ago. Moreover he has determined that history, even narrative history, can be expressed through the use of artefacts and their stories: who made them, when, where and why, and their journey from private to public, as they lose their original function and become remnants. And taken overall this has been the theme, sometimes covert, often subtle, but inescapably there, from exhibitions ranging from the Ice Age to Shakespeare, Vikings to Ming, and Grayson Perry’s The Tomb of the Unknown Craftsman, to name a few. And four years ago, the first audacious and highly successful project – in fact inspiring this one – The History of the World in 100 Objects, as radio and publication but with no exhibition attached.

Now Germany: Memories of a Nation is the three-dimensional complement to MacGregor’s current successful series of radio programmes, each of which examines a single object. There is, of course, in the show itself a subtext about nationality, made perhaps even more piquant because of the recent Scottish referendum, and indicated here by one of the exhibition’s sections being named Floating Frontiers.

Nationhood is exactly what has most eluded the German-speaking peoples, and which has caused, in some respects, the most trouble. The geographic home of the German-speaking peoples has fluctuated widely, from an enormous swathe of princely states, united often acrimoniously under the rather loose rubric of the Holy Roman Empire, though even that organising principle was destroyed by Napoleon. It was the Prussians, not “Germany” who were the great allies at Waterloo. Then there was the Franco-Prussian war, and another new Germany (just as Italy was united). And then the world wars with more wavering boundaries.

It is a patchwork with some, in my view, really glaring omissions: no August Sander portraits, the photographer who documented the German population from high to low for two-thirds of the 20th century; no Christo wrapping the Reichstag in 1995 before its Norman Foster conversion – and instigating the biggest street party Germany had ever seen; no Expressionist masterpiece, no Leica camera.

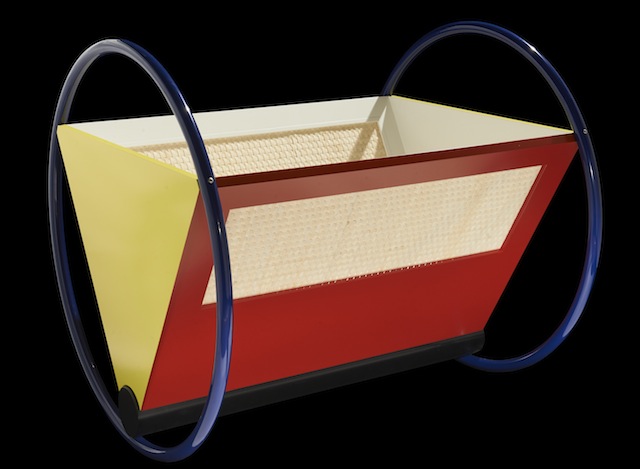

Perhaps most oddly in a show that attempts to elucidate history-changing achievements, from the invention of print and the Reformation to the modernism of the Bauhaus – the latter represented by a marvellously impressive cradle, both elegant and jolly and still in production (pictured right) – little is said of the extraordinary export of people. In the 18th century this island received, to name but a few, the Hanoverian royals and the Hanoverian astronomer Sir William Herschel, and then Prince Albert. In the 20th century émigrés to Anglophone countries included Einstein (an intellectual refugee) and Mies van der Rohe (an economic refugee) and perhaps even the two Austrians Ernst Gombrich and Sigmund Freud, who both fled the Nazis.

Perhaps most oddly in a show that attempts to elucidate history-changing achievements, from the invention of print and the Reformation to the modernism of the Bauhaus – the latter represented by a marvellously impressive cradle, both elegant and jolly and still in production (pictured right) – little is said of the extraordinary export of people. In the 18th century this island received, to name but a few, the Hanoverian royals and the Hanoverian astronomer Sir William Herschel, and then Prince Albert. In the 20th century émigrés to Anglophone countries included Einstein (an intellectual refugee) and Mies van der Rohe (an economic refugee) and perhaps even the two Austrians Ernst Gombrich and Sigmund Freud, who both fled the Nazis.

But we should be deeply grateful for what is on view. The spectrum is very broad. We enter to a film of such exuberant celebration of crowds at the Berlin Wall, accompanied by a modest painted cardboard banner in the colours of the German flag, and the shape of the new Germany, bearing the inscription Wir Sind Ein Volk, with a little heart standing for Berlin. Objects extend from the most humble: a small, worn wooden cart used as transport for people and things as more than 12 million persons were displaced in central Europe in the aftermath of World War II; to the grandest: the 16th-century Strasbourg clock, where Death strikes the bell for the hour, and a hymn tune by Luther is played. There are the Lucas Cranach the Elder studio portraits of Luther himself and his wife Katharina, the ex nun whose homebrewed beer he so appreciated.

Here is a Holbein of Erasmus from Basle, and exquisite German romantic paintings of landscape from Carus to Friedrich. There is a Gutenberg bible, and the four Evangelists, carved in wood by that superb Bavarian Renaissance sculptor Tilman Reimenschneider (main picture). The huge and awkward portrait of the national cultural hero Goethe, writer, poet, botanist, by Tischbein (pictured above left) has a wall to itself. The poet reclines in the Roman Campagna, ivy crawls over an ancient frieze, Germany’s national tree, the oak, is visible, and Goethe, for some obscure reason, has two left feet. Ironically it was given to Frankfurt, a century after it was painted, by a Rothschild.

Here is a Holbein of Erasmus from Basle, and exquisite German romantic paintings of landscape from Carus to Friedrich. There is a Gutenberg bible, and the four Evangelists, carved in wood by that superb Bavarian Renaissance sculptor Tilman Reimenschneider (main picture). The huge and awkward portrait of the national cultural hero Goethe, writer, poet, botanist, by Tischbein (pictured above left) has a wall to itself. The poet reclines in the Roman Campagna, ivy crawls over an ancient frieze, Germany’s national tree, the oak, is visible, and Goethe, for some obscure reason, has two left feet. Ironically it was given to Frankfurt, a century after it was painted, by a Rothschild.

There are some insuperable difficulties. The Holocaust is represented by a gate from Buchenwald, the motto is Jedem das Seine, To Each His Due, designed by a Bauhaus student, and it is suggested, thus subversive. We are told no narrative can encompass the Holocaust, patently untrue when you think of the billions of words, not to mention in London alone a three-story permanent set of galleries narrating just such a tale at the Imperial War Museum. Evil can be explicated, if never understood.

There is a triple ending, marking the extremes perhaps of the past century: Barlach’s Hovering Angel (pictured above), a replica lent by Güstrow’s Protestant cathedral of a pacifist sculpture dedicated to the dead of World War I, the original (1927) destroyed by the Nazis; a model of the rebuilt Reichstag; and an artist’s print by Gerhard Richter – Betty, his daughter, faceless as she is gracefully turns away from us, looking back into a void: beautiful and ambiguous.

There is a triple ending, marking the extremes perhaps of the past century: Barlach’s Hovering Angel (pictured above), a replica lent by Güstrow’s Protestant cathedral of a pacifist sculpture dedicated to the dead of World War I, the original (1927) destroyed by the Nazis; a model of the rebuilt Reichstag; and an artist’s print by Gerhard Richter – Betty, his daughter, faceless as she is gracefully turns away from us, looking back into a void: beautiful and ambiguous.

But every object on view here is worth looking at, and even more, thinking about. Germany changed the world, and its influence is stronger than ever.

![SEX MONEY RACE RELIGION [2016] by Gilbert and George. Installation shot of Gilbert & George 21ST CENTURY PICTURES Hayward Gallery](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_125_x_125_/public/mastimages/Gilbert%20%26%20George_%2021ST%20CENTURY%20PICTURES.%20SEX%20MONEY%20RACE%20RELIGION%20%5B2016%5D.%20Photo_%20Mark%20Blower.%20Courtesy%20of%20the%20Gilbert%20%26%20George%20and%20the%20Hayward%20Gallery._0.jpg?itok=3oW-Y84i)

Add comment