The timing of Gavin Turk’s retrospective couldn’t be better. Last November Joe Corre, son of punk icons Malcolm McLaren and Vivienne Westwood, burned his collection of punk memorabilia in protest at the way the 40th anniversary of punk had become an excuse to institutionalise the movement and transform its anarchic spirit into a marketing opportunity. Having started life as deliberately offensive schmatters, the stuff he destroyed had attained a market value of £5 million. Two weeks later, a blue plaque was erected in Marylebone at 33 Daventry Street, the site of a squat where The Clash singer Joe Strummer lived from 1978-79.

Titled Who What When Where How & Why, Turk’s exhibition invites us to consider how we value cultural rebels and how the meaning (and value) of objects changes according to context. He is fascinated by the process of validation through which outsiders like Joe Strummer, Vincent Van Gogh and Jackson Pollock become cultural heroes and the things they produce treasured icons; and Corre’s angry response to the appropriation of Punk by the establishment creates the perfect climate in which to ponder these questions.

Turk’s most famous work is a blue plaque made to commemorate his time as a student at the Royal College of Art with the words “Gavin Turk Sculptor worked here 1989-1991”. The plaque hangs high up on the wall of an otherwise empty gallery, just as it did in his degree show in 1991. The ironic gesture didn’t gain him a degree, but it did catch the eye of art dealer Jay Jopling who would soon be representing him alongside the likes of Damien Hirst, Tracey Emin and Sarah Lucas: the rest is history.

Turk’s most famous work is a blue plaque made to commemorate his time as a student at the Royal College of Art with the words “Gavin Turk Sculptor worked here 1989-1991”. The plaque hangs high up on the wall of an otherwise empty gallery, just as it did in his degree show in 1991. The ironic gesture didn’t gain him a degree, but it did catch the eye of art dealer Jay Jopling who would soon be representing him alongside the likes of Damien Hirst, Tracey Emin and Sarah Lucas: the rest is history.

Whereas Strummer’s plaque celebrates an anti-establishment rebel, Turk’s was, in itself, an act of defiance. It was the equivalent of saying “watch this space... I may not have achieved much yet, but I have limitless potential.” He identifies, it seems, with those who have the nerve to take on the world and win.

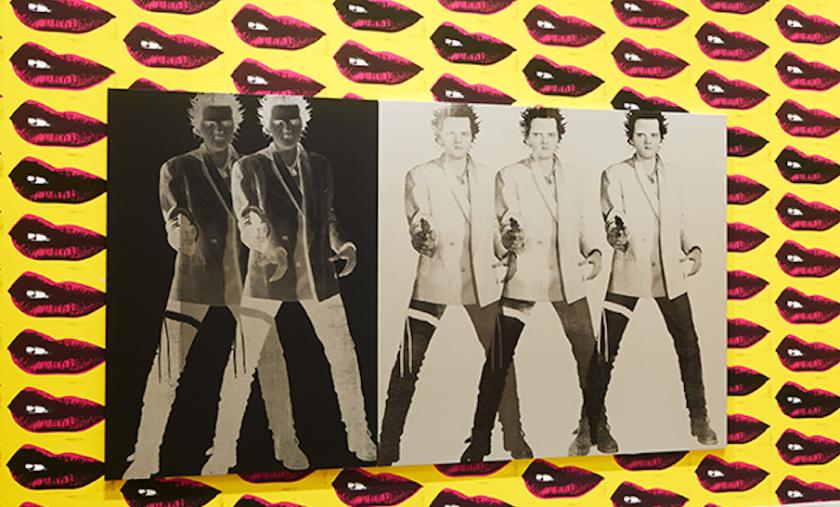

Pop, 2011 (pictured above right) is a Madame Tussaud-style waxwork that shows Turk mimicking Sid Vicious, shooting a pistol into the crowd in the 1980s film The Great Rock ‘n’ Roll Swindle. The trigger-happy pose echoes a publicity shot of Elvis Presley as a gun-toting cowboy in the 1960’s film Flaming Star. Andy Warhol made the image famous with his series of Elvis screen prints and Turk complicates things still further by silkscreening himself (as Vicious, as Elvis) onto canvas in the same pose (main picture).

Turk is a chameleon, able to transform himself into the spitting image not just of Elvis and Sid Vicious, but also Joseph Beuys in his familiar trilby hat, Andy Warhol in a fright wig and Che Guevara in his signature beret. The same goes for an artist’s work. His Jackson Pollock-style drip paintings are incredibly convincing; he achieved them by repeating his own signature over and over again, and once you know this, you begin to discern his name within the elegant web of drips. Not content with plagiarising Pollock’s technique, Turk also recreates the famous photographs taken by Hans Namuth of Jack-the-Dripper at work in his barn.

Is Turk just a clever prankster standing on the shoulders of giants and feeding off their reputations? If he were, the joke would quickly pall; yet his work continues to enthrall because, at bottom, it is not about appropriation so much as evaluation. Since art has no intrinsic value, it is worth what someone is willing to pay for it, and that becomes an act of faith – buoyed up by the Holy Trinity of Originality (the creation of a unique style), Authenticity (the presence of the right signature) and Mythology (the creation of a personal ethos that fosters the notion of genius). The validity of an oeuvre is enhanced when an established dealer lays their reputation on the line and lends it credibility.

Is Turk just a clever prankster standing on the shoulders of giants and feeding off their reputations? If he were, the joke would quickly pall; yet his work continues to enthrall because, at bottom, it is not about appropriation so much as evaluation. Since art has no intrinsic value, it is worth what someone is willing to pay for it, and that becomes an act of faith – buoyed up by the Holy Trinity of Originality (the creation of a unique style), Authenticity (the presence of the right signature) and Mythology (the creation of a personal ethos that fosters the notion of genius). The validity of an oeuvre is enhanced when an established dealer lays their reputation on the line and lends it credibility.

If success in today’s art world relies as much on the personality of an artist as the quality of his or her work, Turk questions every aspect of this process. His signature forms the basis of a long series of works that makes a mockery of the market’s obsession with provenance and authentification. He may play with borrowed ideas and lean heavily on quotation, yet in many ways, his work is surprisingly traditional. Whether paintings, sculptures or graphics, the work is exceptionally well made; so much so that it affirms the (unfashionable) value of craft, an ingredient noticeably missing from the Holy Trinity.

Work that relies on quick-wittedness can easily fall flat: Turk is well aware of the fine line separating success from failure and identifies as much with the underdog as the superstar. He attended the opening of Sensation – the Royal Academy exhibition of work from Charles Saatchi’s collection – dressed as a tramp. The Last Bum, 1999, is a waxwork of this dishevelled persona. He might have emerged from Habitat, 2004, a sleeping bag that has been cast in bronze and painted to resemble the grubby original. Its cousin Nomad, 2002 (pictured below), still seems to have a rough sleeper curled up inside. By addressing both ends of the social spectrum – from those who have nothing to those wealthy enough to collect expensive art – these disquieting objects become emblematic of the shocking disparity that exists between rich and poor, without preaching to anyone. (Pictured above left: Trash, 2006)

The final gallery is dedicated to rubbish. Cuppateano, 2003, stands on the floor beside the gallery guard, as if he had just put down his drink; but the polystyrene cup turns out to be a bronze sculpture, an item to be valued rather than discarded. Scattered around the room are other “worthless” items, such as spent matches, a flat tyre, bin liners full of rubbish, loo rolls and apple cores, all cast in bronze and lovingly painted to resemble trash. A huge skip dominates the space. Painted gloss black, it is a provocation, of course. You might be tempted to throw the sculptures into it as useless rubbish or pretentious crap. Alternatively, though, you might be encouraged to ponder the relationship between the things we cherish and the mountains of stuff we discard – whether they be cheap tat, outdated designer goods or punk memorabilia – and the way that people or things once considered worthless can sometimes be elevated to the status of cultural icons.

The final gallery is dedicated to rubbish. Cuppateano, 2003, stands on the floor beside the gallery guard, as if he had just put down his drink; but the polystyrene cup turns out to be a bronze sculpture, an item to be valued rather than discarded. Scattered around the room are other “worthless” items, such as spent matches, a flat tyre, bin liners full of rubbish, loo rolls and apple cores, all cast in bronze and lovingly painted to resemble trash. A huge skip dominates the space. Painted gloss black, it is a provocation, of course. You might be tempted to throw the sculptures into it as useless rubbish or pretentious crap. Alternatively, though, you might be encouraged to ponder the relationship between the things we cherish and the mountains of stuff we discard – whether they be cheap tat, outdated designer goods or punk memorabilia – and the way that people or things once considered worthless can sometimes be elevated to the status of cultural icons.

- Gavin Turk at Newport Street Gallery until 19 March

- Read more visual arts reviews on theartsdesk

![SEX MONEY RACE RELIGION [2016] by Gilbert and George. Installation shot of Gilbert & George 21ST CENTURY PICTURES Hayward Gallery](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_125_x_125_/public/mastimages/Gilbert%20%26%20George_%2021ST%20CENTURY%20PICTURES.%20SEX%20MONEY%20RACE%20RELIGION%20%5B2016%5D.%20Photo_%20Mark%20Blower.%20Courtesy%20of%20the%20Gilbert%20%26%20George%20and%20the%20Hayward%20Gallery._0.jpg?itok=3oW-Y84i)

Add comment