Francis Alÿs: A Story of Deception, Tate Modern | reviews, news & interviews

Francis Alÿs: A Story of Deception, Tate Modern

Francis Alÿs: A Story of Deception, Tate Modern

Whimsical, charming - and important. Alys dazzles at Tate Modern

In 1994, Francis Alÿs joined the regular hiring-line in the central square in Mexico City. Standing next to plumbers and carpenters with their hand-lettered signs touting their skills, his sign read "Turista", as he offered his ability to be an outsider looking in.

Whimsical, charming, meditative – these are all adjectives that have long been applied to the Belgian artist who has lived and worked in Mexico for a quarter of a century. But with this thrilling retrospective, a new adjective has to be added to the list: important. Alÿs, understated as always, makes no great claims for his works: walking, he says, is simply a way of telling stories. But the stories he chooses make him a narrator of tales that matter. In Re-enactments (pictured right) two films run simultaneously. In one, Alÿs walks through Mexico City with a gun, pointed at the ground, but nonetheless in plain view. No one reacts, no one appears to notice what may well be a hitman on his way a job, or a murderous husband on the rampage. But someone must have noticed, for the film ends with a police car screaming up, a gun aimed at his own head and his arrest. The second film is almost identical: labelled "re-enactment", it recreates that first walk minutely, right down to his arrest and disappearance into the squad-car, yet with different people in the background identically determinedly uninvolved.

In Re-enactments (pictured right) two films run simultaneously. In one, Alÿs walks through Mexico City with a gun, pointed at the ground, but nonetheless in plain view. No one reacts, no one appears to notice what may well be a hitman on his way a job, or a murderous husband on the rampage. But someone must have noticed, for the film ends with a police car screaming up, a gun aimed at his own head and his arrest. The second film is almost identical: labelled "re-enactment", it recreates that first walk minutely, right down to his arrest and disappearance into the squad-car, yet with different people in the background identically determinedly uninvolved.

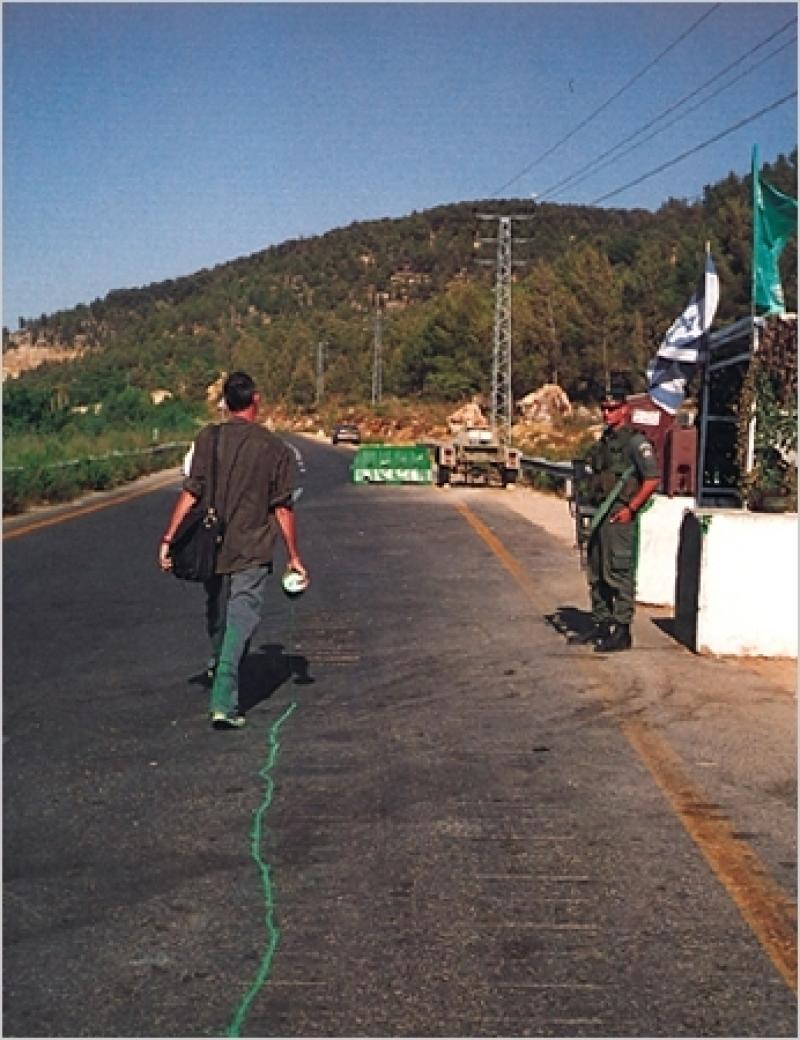

Uninvolvement does not describe the bystanders in The Green Line, a film subtitled “(Sometimes doing something poetic can become political and sometimes doing something political can become poetic)”. Walking, says the artist, is an attitude: it’s “a very immediate and handy way of interacting and eventually interfering within a given context”. The Green Line is the border established by the UN after the 1948 Arab-Israeli war, since breached by Israel, and the artist recreates a political and geographical metaphor literally, drizzling a line of green paint from a leaking can as he goes. No one is uninvolved in this event: shouting children follow him as he nonchalantly strolls; residents watch from their gardens, curious, or annoyed, sometimes just waving to the following camera. In the gallery the film is accompanied by 10 commentators’ views, switched on or off by the viewers. Now all are intertwined: the artist by his action, those filmed as he passes by theirs, the commentators and the gallery-visitors. The walk is no longer a poetic statement, an act of absurdist defiance in the face of an uncaring world, but a gesture of political engagement.

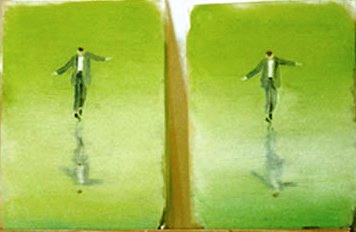

Yet futility is never far from the surface, and Alÿs’ work is an illustration and working-out of the fraud perpetrated on us all by the great con-trick of modernization, that the future will always be bigger, better, shinier, brighter. Paradox of Praxis 1 (Sometimes Doing Something Leads to Nothing) (video below) is the epitome of futility, as Alÿs pushes a rapidly melting block of ice around Mexico City, until all that is left is a rapidly vanishing puddle. Life is hard, the film tells us, and for many, Herculean effort comes to nothing. A Story of Deception, a film shot on an endlessly unrolling road in Patagonia, where watery pools endlessly turn into yet one more mirage, encapsulates much of his work. Despite this, Alÿs’ work, and world, is one of infinite charm. His acrylic paintings, often semi-caricatured in style, have a comic edge, with the figures often looking like they wandered out of a Tintin book, even while they are unsettling – Déjà vu (left) is two identical small panels that show a small gestural brushstroke of a man reflected in a puddle, sited in two different rooms: you see the first, wonder if the reflection is the déjà-vu element, then move on to other pieces; by the time the second pops up in another room, you have forgotten the title, and wonder if you have mistakenly doubled back. Déjà vu not a major piece, but that brief "ping" of uncertainty is achieved with remarkable wit and brevity. A different kind of wit, more pointed, a bit sour, was displayed as Alÿs’ contribution to the 2001 Venice Biennale (not on show here). Asked to participate, Alÿs signalled both his attitude to art-world display, and to his own pride, or otherwise, at being asked, by sending a peacock to represent him.

Despite this, Alÿs’ work, and world, is one of infinite charm. His acrylic paintings, often semi-caricatured in style, have a comic edge, with the figures often looking like they wandered out of a Tintin book, even while they are unsettling – Déjà vu (left) is two identical small panels that show a small gestural brushstroke of a man reflected in a puddle, sited in two different rooms: you see the first, wonder if the reflection is the déjà-vu element, then move on to other pieces; by the time the second pops up in another room, you have forgotten the title, and wonder if you have mistakenly doubled back. Déjà vu not a major piece, but that brief "ping" of uncertainty is achieved with remarkable wit and brevity. A different kind of wit, more pointed, a bit sour, was displayed as Alÿs’ contribution to the 2001 Venice Biennale (not on show here). Asked to participate, Alÿs signalled both his attitude to art-world display, and to his own pride, or otherwise, at being asked, by sending a peacock to represent him. Yet the sheer folly of life is joyously exposed in Rehearsal I (right), a film in which the stops, starts, repetitions and stutters of a brass band rehearsing are synchronized to the image of a Volkswagen Beetle trying (and failing) to drive up a dirt road. When the music stops, the car rolls back; when the music begins again, the car gains traction. As it drives past dusty houses perilously perched on the hill, the car is clearly a metaphor for developing countries and their struggle. Yet all the time, the band resolutely begins again, a brassy, defiant, absurdly hopeful sound as it looks forward – a fine symbol for a fine show.

Yet the sheer folly of life is joyously exposed in Rehearsal I (right), a film in which the stops, starts, repetitions and stutters of a brass band rehearsing are synchronized to the image of a Volkswagen Beetle trying (and failing) to drive up a dirt road. When the music stops, the car rolls back; when the music begins again, the car gains traction. As it drives past dusty houses perilously perched on the hill, the car is clearly a metaphor for developing countries and their struggle. Yet all the time, the band resolutely begins again, a brassy, defiant, absurdly hopeful sound as it looks forward – a fine symbol for a fine show.

- Francis Alÿs, A Story of Deception at Tate Modern until 5 September

Watch Alÿs’ Paradox of Praxis I, 1997

Explore topics

Share this article

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

Monet and London, Courtauld Gallery review - utterly sublime smog

Never has pollution looked so compellingly beautiful

Monet and London, Courtauld Gallery review - utterly sublime smog

Never has pollution looked so compellingly beautiful

Michael Craig-Martin, Royal Academy review - from clever conceptual art to digital decor

A career in art that starts high and ends low

Michael Craig-Martin, Royal Academy review - from clever conceptual art to digital decor

A career in art that starts high and ends low

Van Gogh: Poets & Lovers, National Gallery review - passions translated into paint

Turmoil made manifest

Van Gogh: Poets & Lovers, National Gallery review - passions translated into paint

Turmoil made manifest

Peter Kennard: Archive of Dissent, Whitechapel Gallery review - photomontages sizzling with rage

Fifty years of political protest by a master craftsman

Peter Kennard: Archive of Dissent, Whitechapel Gallery review - photomontages sizzling with rage

Fifty years of political protest by a master craftsman

Dominique White: Deadweight, Whitechapel Gallery review - sculptures that seem freighted with history

Dunked in the sea to give them a patina of age, sculptures that feel timeless

Dominique White: Deadweight, Whitechapel Gallery review - sculptures that seem freighted with history

Dunked in the sea to give them a patina of age, sculptures that feel timeless

Bill Viola (1951-2024) - a personal tribute

Video art and the transcendent

Bill Viola (1951-2024) - a personal tribute

Video art and the transcendent

In the Eye of the Storm: Modernism in Ukraine 1900-1930s, Royal Academy review - famous avant-garde Russian artists who weren't Russian after all

A glimpse of important Ukrainian artists

In the Eye of the Storm: Modernism in Ukraine 1900-1930s, Royal Academy review - famous avant-garde Russian artists who weren't Russian after all

A glimpse of important Ukrainian artists

Francis Alÿs: Ricochets, Barbican review - fun for the kids, yet I was moved to tears

How to be serious and light hearted at the same time

Francis Alÿs: Ricochets, Barbican review - fun for the kids, yet I was moved to tears

How to be serious and light hearted at the same time

Gavin Jantjes: To Be Free, Whitechapel Gallery review - a sweet and sour response to horrific circumstances

Seething anger is cradled within beautiful images

Gavin Jantjes: To Be Free, Whitechapel Gallery review - a sweet and sour response to horrific circumstances

Seething anger is cradled within beautiful images

Laura Aldridge / Andrew Sim, Jupiter Artland, Edinburgh review - lightness and joy

Two Scottish artists explore childhood and play

Laura Aldridge / Andrew Sim, Jupiter Artland, Edinburgh review - lightness and joy

Two Scottish artists explore childhood and play

Judy Chicago: Revelations, Serpentine Gallery review - art designed to change the world

At 84, the American pioneer is a force to be reckoned with

Judy Chicago: Revelations, Serpentine Gallery review - art designed to change the world

At 84, the American pioneer is a force to be reckoned with

Now You See Us: Women Artists in Britain 1520-1920, Tate Britain review - a triumph

Rescued from obscurity, 100 women artists prove just how good they can be

Now You See Us: Women Artists in Britain 1520-1920, Tate Britain review - a triumph

Rescued from obscurity, 100 women artists prove just how good they can be

Add comment