Andy Warhol: The Portfolios, Dulwich Picture Gallery | reviews, news & interviews

Andy Warhol: The Portfolios, Dulwich Picture Gallery

Andy Warhol: The Portfolios, Dulwich Picture Gallery

An exhibition of still lifes which are anything but still

The first room of Andy Warhol: The Portfolios at Dulwich Picture Gallery made me regret coming. The second room made me never want to leave. The first has 10 of the Flowers and 10 of the Campbell's Soup Cans, four weedy sunsets and one Marilyn in pink, purple and brown - hardly any nourishment, certainly nothing fresh.

Luckily, there was also Birmingham Race Riot (1964) (pictured below right), which shows what was subtle and original in Warhol's work. A black and white screenprint (apt for a piece on racism), this shows a white policeman with his baton standing by as two ferocious police dogs attack a black man, one dog ripping into his trousers. The image seems to shift between blocky screenprint and mottled watercolour, both monumentalising and fictionalising this encounter, suggesting artistic and literal truths. It is this shifting between reality and fiction which is one of Warhol's greatest successes, and this is proved in the next room.

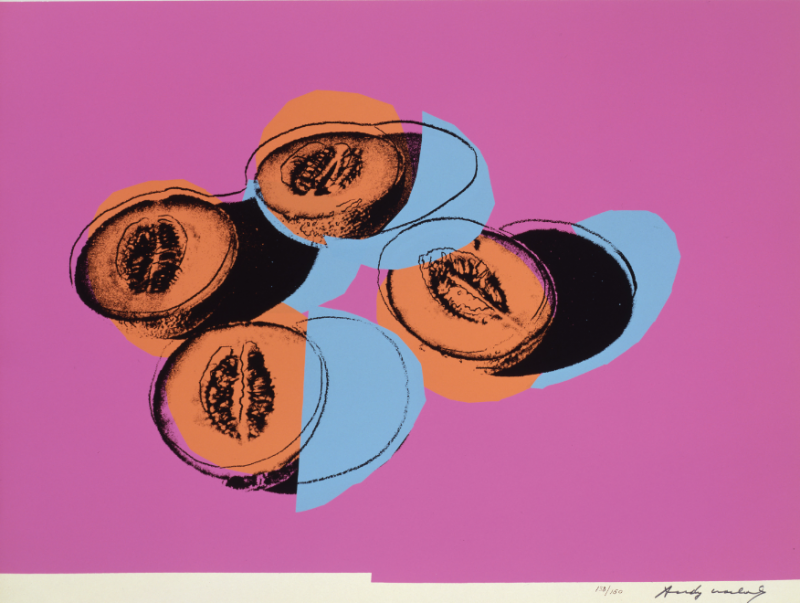

Space Fruit: Still Lifes (1979), which are on the surface gaudy fruit screenprints, are transfixing explorations of the nature of painting and reality which reassert quite what a genius of the image Warhol was. I sat in front of them taking in the galaxy of ideas and questions Warhol fixed into them, captured by their beauty, their rigour and their nature which oscillates between reality, illusion and immateriality.

Take Cantaloupes II (main picture). Four cantaloupe halves lie - where? They can't be on a table because they are viewed from different perspectives - they don't seem to sit right. Some of their shadows fall beneath other colour planes, some above. The cantaloupes are luminously orange, except their orange ovals seep beyond their lines. There are intrusive light blue circles and semi-circles, and this all sits on large pink blocks, which don't quite occupy the entire paper.

All of these things serve to discomfort but also to draw you in. The fruit hover between realistic portrayals, cartoon outlines, present objects, colourful abstracts. Everything bleeds across borders of reality. The colours do not just highlight the transitions between these states but enable them by allowing us to dismantle the image. You can never stop looking because each piece of fruit is in perpetual flux: the life in these melons is anything but still.

All of these things serve to discomfort but also to draw you in. The fruit hover between realistic portrayals, cartoon outlines, present objects, colourful abstracts. Everything bleeds across borders of reality. The colours do not just highlight the transitions between these states but enable them by allowing us to dismantle the image. You can never stop looking because each piece of fruit is in perpetual flux: the life in these melons is anything but still.

The best thing is that there are six different pictures in this series here, each with its own challenge to the nature of the image, each a challenge to still lifes of the past and a tribute and answer to Cezanne with his apples. You could spend hours caught in their shifting, puzzling beauty.

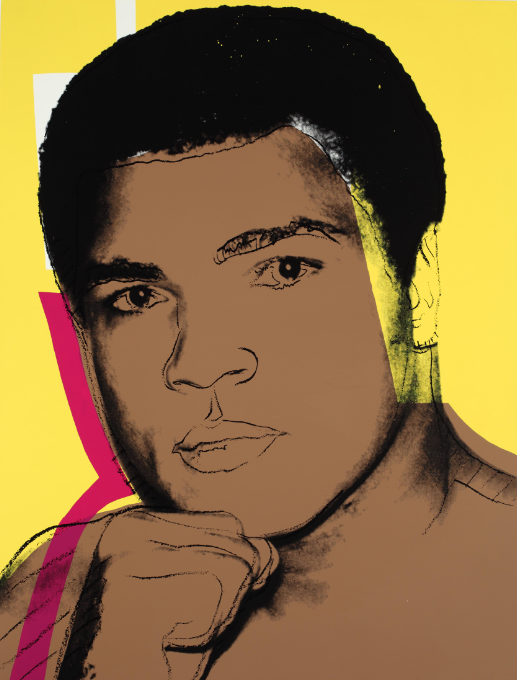

The third room returns to celebrity subject-matter, but after Space Fruit their whirling possibilities become all the more entrancing. Muhammad Ali (1978) (pictured above left) reanimates Cubism with a Pop shot in the arm, using four different angles on Ali in one series, as opposed to the multiples of one picture as with the Marilyns. Again, Warhol's use of colour both fictionalises and reifies Ali, which means his portraits of the famous don't become adorations. Are these people real? The portraits don't help us.

Muhammad Ali hangs alongside Ten Portraits of Jews of the Twentieth Century (1980), where Warhol took his distortive use of blocks of colour even further. Frank Kafka is mostly pale blue, but a tiny radius of yellow begins and is quickly extinguished, while a deeper blue triangle points at his left eye. A rogue blue block sneaks in from the bottom. He is abstracted and terrified, mysterious and modern. A blue rectangle is slapped onto Louis Brandeis' forehead and the whole picture feels like it's coming dangerously close to abstraction. Einstein is mainly drawn lines, rather than a photo.

Warhol has gone back to what he knows best: kitsch

Given the subject matter - modern Jews - this technique feels fitting: the shocking colours and glaring blocks are a hysterical response to hysterical, dangerous times; the use of photos and lines permits a shifting between mythology and reality; and there is that comedy-tragedy vital to traditional Jewish humour.

The final room is crowded like Morozov's drawing room, twenty pictures hanging from three walls. Drawn from the Myths (1981) and Endangered Species (1983) series, it feels like we have regressed somewhat. The daring years 1979-1981 have ended up where they started, with rather ordinary Warhols, if there can be such a thing: pop culture icons in bright colours. The spirit of exploration seen in the previous two rooms has subsided and Warhol has gone back to what he knows best, kitsch.

If the flanks of Andy Warhol: The Portfolios disappoint, the central rooms thrill, more than thrill - entrance, excite and enliven. If you want fresh evidence of Warhol's genius, it's only three stops from Victoria Station.

GREAT POP ART RETROSPECTIVES

Allen Jones, Royal Academy. A brilliant painter derailed by an unfortunate obsession

Ed Ruscha: Fifty Years of Painting, Hayward Gallery. First British retrospective for a modern master

Ed Ruscha: Fifty Years of Painting, Hayward Gallery. First British retrospective for a modern master

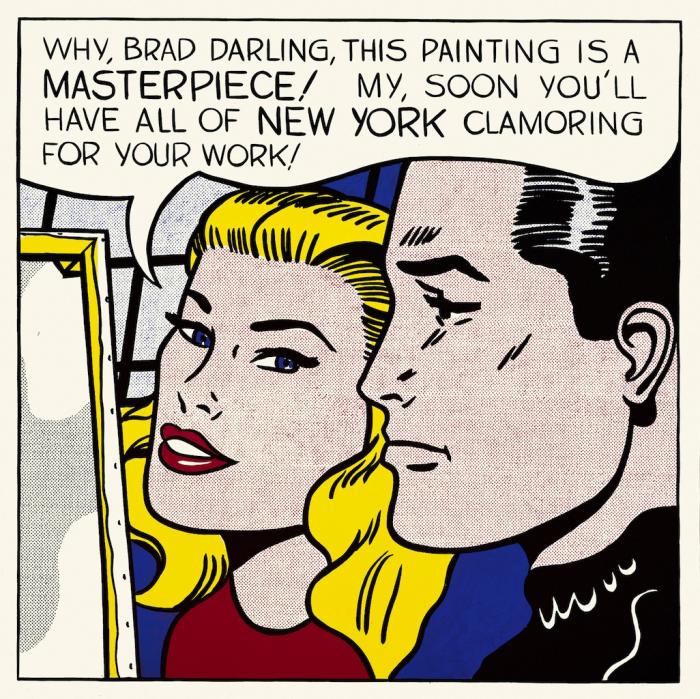

Lichtenstein: A Retrospective, Tate Modern. The heartbeat of Pop Art is given the art-historical credit as he deserves (pictured above, Lichtenstein's Masterpiece, 1962)

Patrick Caulfield, Tate Britain. A late 20th-century great emerges into the light

Pauline Boty: Pop Artist and Woman, Pallant House Gallery. The paintings are wonderful, but the curator does a huge disservice to this forgotten artist

Richard Hamilton, Tate Modern /ICA. At last, the British 'father of Pop art' gets the retrospective he deserves

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

more Visual arts

Yinka Shonibare: Suspended States, Serpentine Gallery review - pure delight

Weighty subject matter treated with the lightest of touch

Yinka Shonibare: Suspended States, Serpentine Gallery review - pure delight

Weighty subject matter treated with the lightest of touch

Jane Harris: Ellipse, Frac Nouvelle-Aquitaine MÉCA, Bordeaux review - ovals to the fore

Persistence and conviction in the works of the late English painter

Jane Harris: Ellipse, Frac Nouvelle-Aquitaine MÉCA, Bordeaux review - ovals to the fore

Persistence and conviction in the works of the late English painter

Sargent and Fashion, Tate Britain review - portraiture as a performance

London’s elite posing dressed up to the nines

Sargent and Fashion, Tate Britain review - portraiture as a performance

London’s elite posing dressed up to the nines

Zineb Sedira: Dreams Have No Titles, Whitechapel Gallery review - a disorientating mix of fact and fiction

An exhibition that begs the question 'What and where is home?'

Zineb Sedira: Dreams Have No Titles, Whitechapel Gallery review - a disorientating mix of fact and fiction

An exhibition that begs the question 'What and where is home?'

Yoko Ono: Music of the Mind, Tate Modern review - a fitting celebration of the early years

Acknowledgement as a major avant garde artist comes at 90

Yoko Ono: Music of the Mind, Tate Modern review - a fitting celebration of the early years

Acknowledgement as a major avant garde artist comes at 90

Unravel: The Power and Politics of Textiles in Art, Barbican review - the fabric of dissent

An ambitious exploration of a neglected medium

Unravel: The Power and Politics of Textiles in Art, Barbican review - the fabric of dissent

An ambitious exploration of a neglected medium

When Forms Come Alive, Hayward Gallery review - how to reduce good art to family fun

Seriously good sculptures presented as little more than playthings or jokes

When Forms Come Alive, Hayward Gallery review - how to reduce good art to family fun

Seriously good sculptures presented as little more than playthings or jokes

Entangled Pasts 1768-now, Royal Academy review - an institution exploring its racist past

After a long, slow journey from invisibility to agency, black people finally get a look in

Entangled Pasts 1768-now, Royal Academy review - an institution exploring its racist past

After a long, slow journey from invisibility to agency, black people finally get a look in

Barbara Kruger, Serpentine Gallery review - clever, funny and chilling installations

Exploring the lies, deceptions and hyperbole used to cajole, bully and manipulate us

Barbara Kruger, Serpentine Gallery review - clever, funny and chilling installations

Exploring the lies, deceptions and hyperbole used to cajole, bully and manipulate us

Richard Dorment: Warhol After Warhol review - beyond criticism

A venerable art critic reflects on the darkest hearts of our aesthetic market

Richard Dorment: Warhol After Warhol review - beyond criticism

A venerable art critic reflects on the darkest hearts of our aesthetic market

Dineo Seshee Raisibe Bopape: (ka) pheko ye / the dream to come, Kiasma, Helsinki review - psychic archaeology

The South African artist evokes the Finnish landscape in a multisensory installation

Dineo Seshee Raisibe Bopape: (ka) pheko ye / the dream to come, Kiasma, Helsinki review - psychic archaeology

The South African artist evokes the Finnish landscape in a multisensory installation

Paul Cocksedge: Coalescence, Old Royal Naval College review - all that glitters

An installation explores the origins of a Baroque masterpiece

Paul Cocksedge: Coalescence, Old Royal Naval College review - all that glitters

An installation explores the origins of a Baroque masterpiece

Add comment