Given that Edward Bond, that most austere of playwrights, has refused to allow a London production of his most notorious play, Saved, for over a quarter of a century, it’s neither surprising nor unwise that having been granted the rights, director Sean Holmes is respectful of the text. You can, however, have too much of a good thing. Long before the three hours and five minutes' running time is up, you realise that in this over-deliberate production respect has curdled into reverence.

It’s not hard to see why. This, after all, is a rare opportunity to set the record straight on a play whose arresting quality is overshadowed by the fact that it was banned on its original 1965 run by the Lord Chamberlain’s office of censorship, principally for its pivotal scene in which five lads larking around in a park stone a baby to death. Forty-six years on, the scene understandably retains its power to shock but although the behaviour depicted is, by definition, irresponsible, the writing most certainly is not.

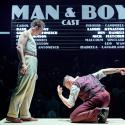

The baby belongs to 23-year-old Pam (a shrill and convincing Lia Saville) whom we first meet in her parents’ living room where, comically, she’s trying to have sex with Len (Morgan Watkins, pictured below with Saville), a nondescript younger man she has just met. Despite the stagnant atmosphere in Pam’s sullen home – her angry and unhappy parents do not speak to one another – Len moves in. But Pam tires of him and takes up with the more handsome Fred (nastily self-assured Calum Callaghan) and proceeds to have his baby.

Part of the play’s potentially gripping power resides in Bond’s vivid, spare dialogue

Unlike Pam and Fred who refer to the baby as “it”, Len is devoted to the child. But his kindness and concern drives Pam to distraction. Desperate to hold onto self-obsessed Fred she leaves the baby with him in the park to look after. But although his subsequent actions are revealed to have consequences, Bond is ruthlessly unsentimental in his second act which, in part, looks at how little most people learn.

Yet Saved is, Bond insists, a play governed by optimism, as seen through the character of Len. In Morgan Watkins’s gently affecting performance he’s weak but has a generosity born, crucially, of compassion. That saving quality shines through the smothering climate of casual cruelty springing from the extreme emotional and social deprivation that engulfs everyone, not least the audience.

Part of the play’s potentially gripping power resides in Bond’s vivid, spare dialogue. There’s barely a speech that runs longer than one line but the gaps and elisions are starkly poetic with a cumulative effect that manages to feel both eloquent and, alas, still urgent. Holmes then dedicates himself to underlining every possible moment for its given or received hurt, but that comes at a cost: dramatic rhythm is sacrificed, which has dangerous consequences of its own, not least in the big scene.

Part of the play’s potentially gripping power resides in Bond’s vivid, spare dialogue. There’s barely a speech that runs longer than one line but the gaps and elisions are starkly poetic with a cumulative effect that manages to feel both eloquent and, alas, still urgent. Holmes then dedicates himself to underlining every possible moment for its given or received hurt, but that comes at a cost: dramatic rhythm is sacrificed, which has dangerous consequences of its own, not least in the big scene.

In the years since the play’s premiere, there have been numerous detailed media accounts of violence towards children so the terrifying attack on the child initially feels horribly plausible. But the too patient rhythm of the playing allows both the audience and the characters time to detach themselves from the horror. And the more removed everyone becomes, the less convincing the scene grows.

Audiences think far faster than this production believes. Looks, pauses and whole scenes feel increasingly over-extended. The resulting earnestness spills over into the performances, almost all of which are pushed beyond the genuinely emotional to the pitch of (over)emoting. And once characters start screaming, audiences stop listening because the effect is so generalised.

That sits particularly oddly in a production in which nothing is unconsidered. Paul Wills’s fiercely unadorned set design – a back wall flown in and out and isolated items of furniture – follows Bond’s instruction about the stage remaining as bare as possible. The starkness of the presentation is then further emphasised by Oliver Fenwick‘s hard, bright light that unsparingly delineates the transitions as much as the 13 scenes themselves.

People walk in and out of scenes slowly, as if presenting their every attitude for serious scrutiny. It creates a mood of acute self-consciousness that becomes most painful in the final scene which, famously, has only one spoken line – the rest being a precise set of stage directions for the characters all terminally trapped together in the same room.

The decision to push that final scene to a degree of stylisation bordering on ballet looks to be the result of advice from Bond himself who has written about the mythic nature of his writing in admonishment of, for him, too naturalistic an approach. But pushing performance toward ritual is good for religion and bad for engaging, developing drama. Seeing the play on stage, the vastness of its influence is there for all to see. Rafts of Royal Court writers from Caryl Churchill and Sarah Kane to Simon Stephens follow in its wake. But this production proves that one should trust the play, not the playwright.

- Saved at the Lyric Hammersmith until 5 November

Add comment